NEVER, EVER DO THIS: Gentle Advice for Eager Writers (Part 3)

Imagine …

You’re trudging through a vast desert, with a star-filled night sky hanging above your head.

Sand particles attack your eyes as the howling wind kicks up dust. The chill in the air threatens to freeze you to the bones.

And yet, you persist onwards. There is no other way but forward.

Just then, the ground before you shifts. A nearby dune starts to move. And before you know it, a gigantic head protrudes from the Earth, made up entirely of coarse, gravely sand.

It’s like in Aladdin, when the protagonist summons a tiger’s head to fetch a magic lamp. But this is 10,000 times more awesome. Cause it’s, you know, my head.

“WHO DARES DISTURB MY SLUMBER?!” I roar, as you peel back the hood of your turban.

“It is I,” you say, “the diamond in the rough! I have come seeking your knowledge, wisdom, and weird out-of-the-box analogies that make me a better writer!”

“HMMMMM,” I ponder, “ARE YOU TRULY DESERVING OF MY INSIGHT MORTAL?”

“Please … It’s been so long since you gave out writing tips, and my spec is in dire need of attention!”

“VERY WELL,” I say, “FIVE MORE TIPS ON HOW TO NOT ANNOY YOUR READER SHALL BE YOURS. BUT LISTEN WELL, YOU BABY WRITER. BECAUSE I’M ONLY GOING TO SAY THIS ONCE …”

#1 – DO NOT NAME EVERY SINGLE CHARACTER IN YOUR SCRIPT

OK, I’m dropping the whole Tiger-God schtick now. Mostly because I hate sand. It’s rough and irritating and it gets everywhere …

But seriously, back to the point, wayyyyyy too many writers will take the time to name every single character in their screenplay. Even down to people who have one line or show up in a single scene. And this is entirely unnecessary.

Why? Because the reader can only keep track of so many names at one given time. If you give me three or four people I need to pay attention to over 120ish pages, chances are good that I’ll be able to handle that assignment. If you give me seven or eight names … OK, a little harder. But yeah, I can probably manage.

But if you double that amount … if you start getting into fifteen, sixteen, seventeen. Maybe even twenty or more names that I have to remember in a whole screenplay. Yeah, you’re asking for trouble.

You have to remember that novel writing is not the same as screenwriting. You have exponentially less time to get information across to the audience than you do in a book. Novels can have 500+ pages, 100,000+ words. It takes days, weeks, maybe a month to read a book, depending on your speed. Films are over and done with in a matter of hours (or a day if you count the runtime of Avatar: Way of Water). So, with that in mind, you can’t expect to deliver the same amount of information in a screenplay as you can in a book. Sorry, but this rarely works.

I highly encourage all of you to instead DE-name as many people as you can. Obviously, if someone has a truly important role to play, then they deserve a name. It’d be weird to call your leading lady “LOVE INTEREST” when she has a hundred lines.

But that Doctor who’s only in one scene to deliver a bad medical diagnosis? Just call him DOCTOR. Or the cop who arrests your protagonist as the inciting incident? Perfectly fine to just call him OFFICER on the page.

And hell, even if these people DO come back again, you can probably still get away with this. Cause I’m much more likely to remember DOCTOR on page 70 than I am to remember MARCUS. Seriously, in the latter instance, I’m probably flipping back through the script to figure out who that is.

#2 – DO NOT WRITE OUT SONG LYRICS AS DIALOGUE

For a couple of reasons.

Number one, dialogue takes up a LOT of space on the page. One of the fastest ways to cut down on page count in your spec is to cut speaking lines galore.

But the second and more important reason not to do this is that 99.99999% of the time, I’m not going to read this anyway.

Why not, you ask? Because what am I supposed to do? Imagine the song playing in my head? I have no idea what the musical accompaniment is like. I don’t know if the tempo is fast or slow. And even if your song lyrics are witty beyond belief, not being able to hear the music is a HUGE issue for me. It basically cancels out, like 80% of why you’re including this in the first place.

So, if you’ve got a scene set in an old-timey bar where a beautiful gal is serenading the crowd, I really wouldn’t include the lyrics. Yes, even if they somehow tie into the theme or tone of your film.

The only exception to this rule MIGHT be if the lyrics are an important plot point for later ...

But even then, I’d probably recommend you find a different way to do that.

#3 – DON’T OVERLOAD YOUR SCRIPT WITH HANGERS

And no, I’m not talking about that thing in the coat closet that you never use (seriously, learn to do laundry).

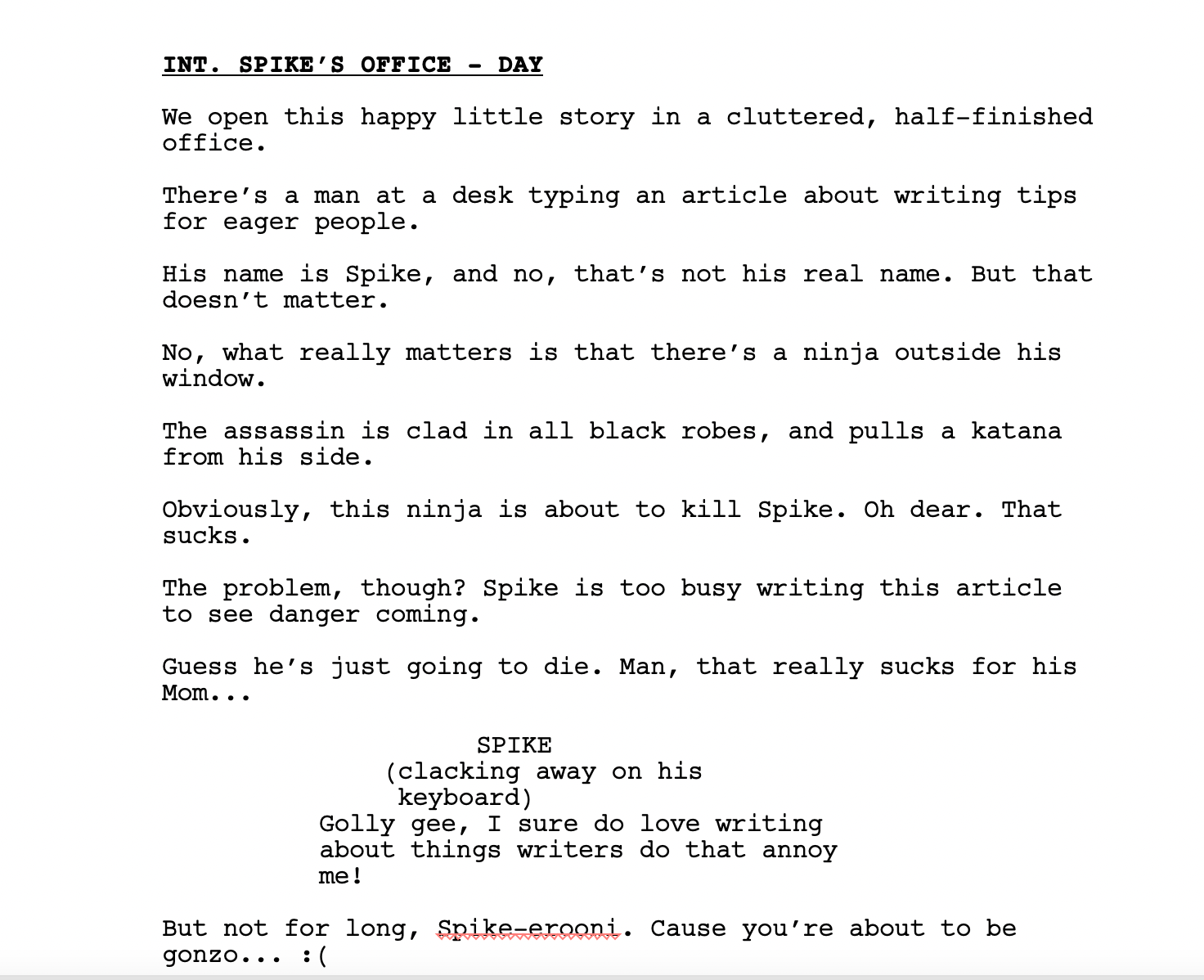

I’m talking about script hangers—those little one- or two-word bits that don’t fit cleanly on the page. Instead, they hang out over the edge, creating an entirely new line which then takes up a lot of space. Like this:

Do you see what’s happening here? In this happy little example I just wrote, I’m wasting almost half the page with hangers! If I were more efficient with my verbiage … if I cut a few words or, hell, even a few characters from what I was writing every line, I would have SO MUCH MORE SPACE with which to tell this story! Heck, we might even find out if Spike succumbs to that troublesome ninja or not! The world is our oyster!

“But Spiiiiiiiiike, I like how this sentence sounds! It’s perfect and showcases—”

SMACK!

“NO! Stop that!”

Find a different way to say what you want to say! No arguing. No discussion!

In 99% of all circumstances, there’s a different way to get the same point across in your writing. Even if that different way is only a few characters shorter than before. Because sometimes, by changing those few characters, you can delete a whole line, and move an entire scene heading from one page to the next. And if you do that enough times throughout your screenplay, you’ll save pages and pages and pages off your read.

And if you’ve read any of my other articles on writing, you already know how goddamn important it is to cut length off your story by any means necessary.

#4 – DON’T INCLUDE INFORMATION THAT IS NOT ABSOLUTELY ESSENTIAL TO THE SCENE

This one seems really simple, but I’m writing about it so clearly, it’s a problem.

Imagine for a moment that you’re writing a courtroom scene. The defendant is your protagonist, and he silently watches the judge and his lawyer discuss his case.

In this scenario, you know a few things that DON’T matter to the story?

The bailiff. The stenographer. What the floors are made of. What you can see out of the windows. Or how many people are in the stands watching (unless, of course, one of the spectators is important to the story and comes back later).

My point is—too many young writers include far too many extraneous details! Go back to my point above about asking a reader to keep track of too much. If it isn’t an important detail that impacts your larger narrative, why would you waste precious time on it??

Yeah, yeah, yeah. I know what you’re about to say, Spike. “I’m setting the scene, Spike.” “I’m painting a picture.” “Don’t cramp on my artistic vision.”

Look, do whatever you want, man. But know that whenever I read a script with a bunch of things in it that don’t matter, I get bored really quickly. And in this game, you can’t allow your audience to get bored.

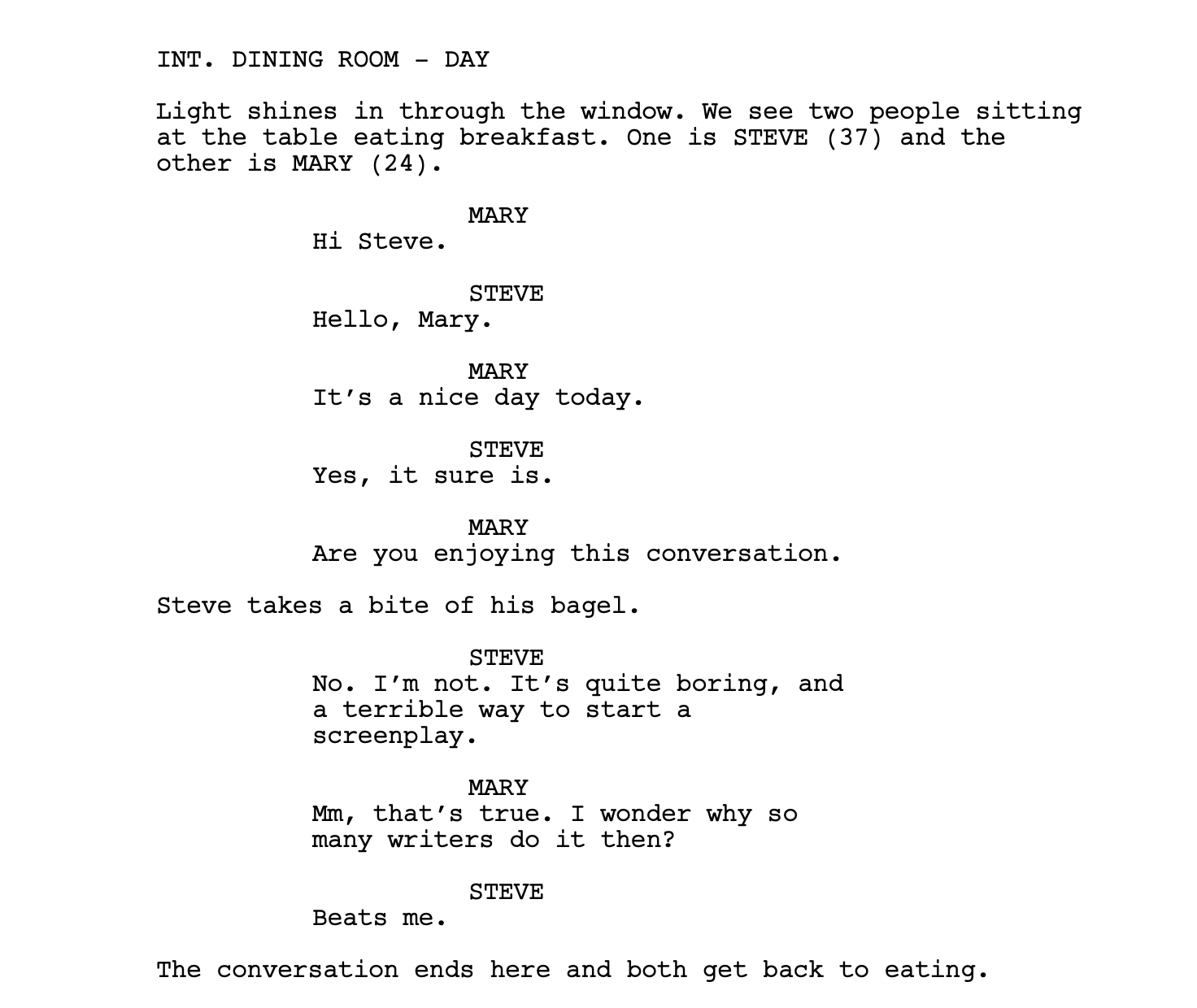

#5 – DON’T START YOUR SCRIPT LIKE THIS!

Because no one EVER wants to read a script that starts with this kind of opening. It’s the clearest possible sign that someone isn’t ready for the big-time.

Ignore the sarcastic dialogue that I wrote for this example … just think about if you were to pick up a brand new spec, start reading, and immediately be thrown into a scene … There’s no introduction, no unique opening image, no character descriptions that help you as the audience understand who is talking or what is happening …

This script basically just plops you down into the middle of an already active universe, one you don’t understand at all, and expects you to get up to speed immediately. And it’s an expectation that is frankly unreasonable.

Readers shouldn’t have to do all the hard work ourselves (we should do SOME but not all). Instead, you (the writer) should guide us through your story in a clear and deliberate way.

Rather than just dropping us in the middle of the woods with no guidance on where to go or how to get out, instead take us by the hand and walk us to where you want to go. Take us on a curated tour of the wilderness, showing us exactly what we need to see when we need to see it.

Because I guaran-fucking-tee that if you don’t, we’ll be all but out of your script by around page 10. Just being honest here.

Godspeed y’all, and happy writing.

*Feature Image: Portrait of Anna Maria van Schurman by Jan Lievens / Wikimedia Commons