Why Do So Many Sequels Suck?

I knew the Saw franchise was in trouble from the moment in its third film where the rib cage of Detective Kerry (Dina Meyer) was ripped apart by one of Jigsaw’s contraptions.

What made it so egregious in the franchise? For being a good detective, the killer offed Kerry, but that went against the grain of his modus operandi and any logic the series of films had set up previously. The premise was that Jigsaw had beaten cancer and proceeded to go about teaching painful lessons to those who stopped appreciating the gift of life. That’s a lot different from the actions of a shrewd and seasoned detective who was after him.

By betraying the series’ very premise, the filmmakers made it clear that they valued show-stopping gore at any cost over any semblance of consistency or fair plotting. By that second sequel to the original, the Saw series was not worth watching anymore.

Why do some sequels go so wrong? What eggs filmmakers on to make such dunderheaded moves as forgetting the essence of a premise and compromising the integrity of the intellectual property?

Granted, it’s never an easy task writing sequels and trying to live up to the standards of a standout original. Some wonderful sequels do exist however, even though they’re a rare breed. The Godfather Part II, Spider-man 2, and both The Road Warrior and Mad Max: Fury Road come readily to mind. Yet, unfortunately, too often sequels are simply terrible (Jaws 2 or 3, anyone?). The horror realm seems to get hit particularly hard as screenwriters will often throw the baby out with the bath water to justify any heightened sense of bloodletting or frights that they can conjure. Such wrongful thinking not only plagued the Saw sequels, but they took a chainsaw to the reputations of various franchises like Friday the 13th and Predator, too. Within each subsequent sequel in those properties, the results far too often meant utterly diminished returns.

Recently, the Paranormal Activity franchise struggled mightily to retain what was great about the first one. The original 2007 sleeper, written and directed by Oren Peli, created a simple template for horror: spook up a house with ghosts and demons and have it all videotaped. That premise should have yielded a ton of easy sequels: haunted graveyards, school dormitories, abandoned warehouses, hospitals, you name it. If there’s a camera there, it can chronicle that place’s ghost story. New characters, new plots, new locations, and all one needed to do was keep the same genius, butt-simple premise of a tranquil setting being disrupted by things that go bump in the night and filmed accordingly.

Easy, right?

Apparently not.

For some reason, that film’s powers-that-be decided that the true premise of the franchise was not how normal people handle a ghost in their midst but rather, the elaborate backstory of the female lead Katie, her sister Kristi, and a demonic coven wreaking havoc since their childhood. By the third film, the franchise had become so bogged down in conspiracies, flashbacks, and incomprehensible plotting, the franchise dithered away its opportunity to keep the videotaping story at the core and create a more sustainable series. I stopped relating to a story about normal people dealing with the supernatural and grew bored by these twisted sisters.

Writers by their very nature want to push boundaries and that often means thinking outside of the box, but when writing a sequel, it shouldn’t mean straying too far afield of that given box. Best to remember that adage about storytelling in Hollywood: What is the plot, and what is the story really about?

What is the plot? What is its essence? That’s what too many sequels forget.

Saw sequels were preoccupied with finding the most fantastical ways to hack bodies to bits, but the essence of the Saw premise is about a survivor teaching violent lessons to those who don’t value their own lives. It’s not about building better mousetraps. Paranormal Activity was about a regular world being usurped by otherworldly forces, not crazed witches.

As Hannibal Lecter explained to Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs, the essence of the serial killer she was hunting, that which was in “his nature,” wasn’t about killing women. It was about coveting. “Buffalo Bill” wanted to own what he saw, namely various women he wanted to emulate. Thus, he kidnapped and killed them so he could wear their skins and be feminine like they were. Films are about essences, too—what’s really at stake and why should I care?

Interestingly enough, for a film that talked about nature and essentials, the sequels to The Silence of the Lambs forgot what it was really about. The story was not about Lecter, but rather the fledgling FBI agent trying to do her job well. The TV series captured the flavor better, albeit concentrating on a more experienced agent, with Lecter more in support where he should be. Still, the NBC show did manage to confuse matters by giving the show the title Hannibal.

Spider-Man 2 succeeded as a sequel, whereas Spider-Man 3 did not, because it kept its focus on protagonist Peter Parker and not the antagonists. Too many villains marred the third one with Peter fighting for screen time alongside three baddies: the Green Goblin, Sandman and Venom. The essence of Spider-Man, what his story is about, is the struggles of a regular Joe to be a superhero. The MCU does an excellent job of remembering that in its films. The Avengers may be superheroes of some ilk or another, but they’re vulnerable, recognizable human beings, too.

Sometimes, a great sequel can surpass the original, as in the case of Addams Family Values. Relieved of the need to introduce the whole premise, the sequel was able to concentrate on how the addition of a new baby changed the dynamics of an already bizarre family across three generations: Gomez, Uncle Fester, and Wednesday. The baby added havoc to their story the way they brought craziness to the rest of the world—a nice twist, indeed.

Additionally, Addams Family Values screenwriter Paul Rudnick realized that the property always took a counter-culture attitude towards the status quo in America, and such themes seemed even more necessary during the hypocritical “Moral Majority” era of the late 80s and early 90s. It not only rang true to him as a gay man living in a nation whose leaders were marginalizing those not of traditional family stripes but going about it in brazen ways that only underlined the hypocrisy. Ronald Reagan may have started out his term rescuing the Americans held hostage in Iran, but less than a term later, he was funding similar foreign rebels in another beleaguered nation.

Sometimes a sequel can be quite different from the original film and still thrive. That’s certainly true of the James Bond franchise that started on the big screen with Dr. No and has now seen six actors playing the suave spy over seven decades. Each of its subsequent sequels was adapted to the times and the gifts of the actors, accordingly, and by and large, most of them worked in playing with the tropes of the formula. Roger Moore’s lighter fare befit the sillier 70s, whereas Daniel Craig’s darker spy was in times with our post-9/11 world. However, the essence of Bond remained no matter who played him. The story was always about one man making a difference, and often saving the world in his actions, no matter who the villain.

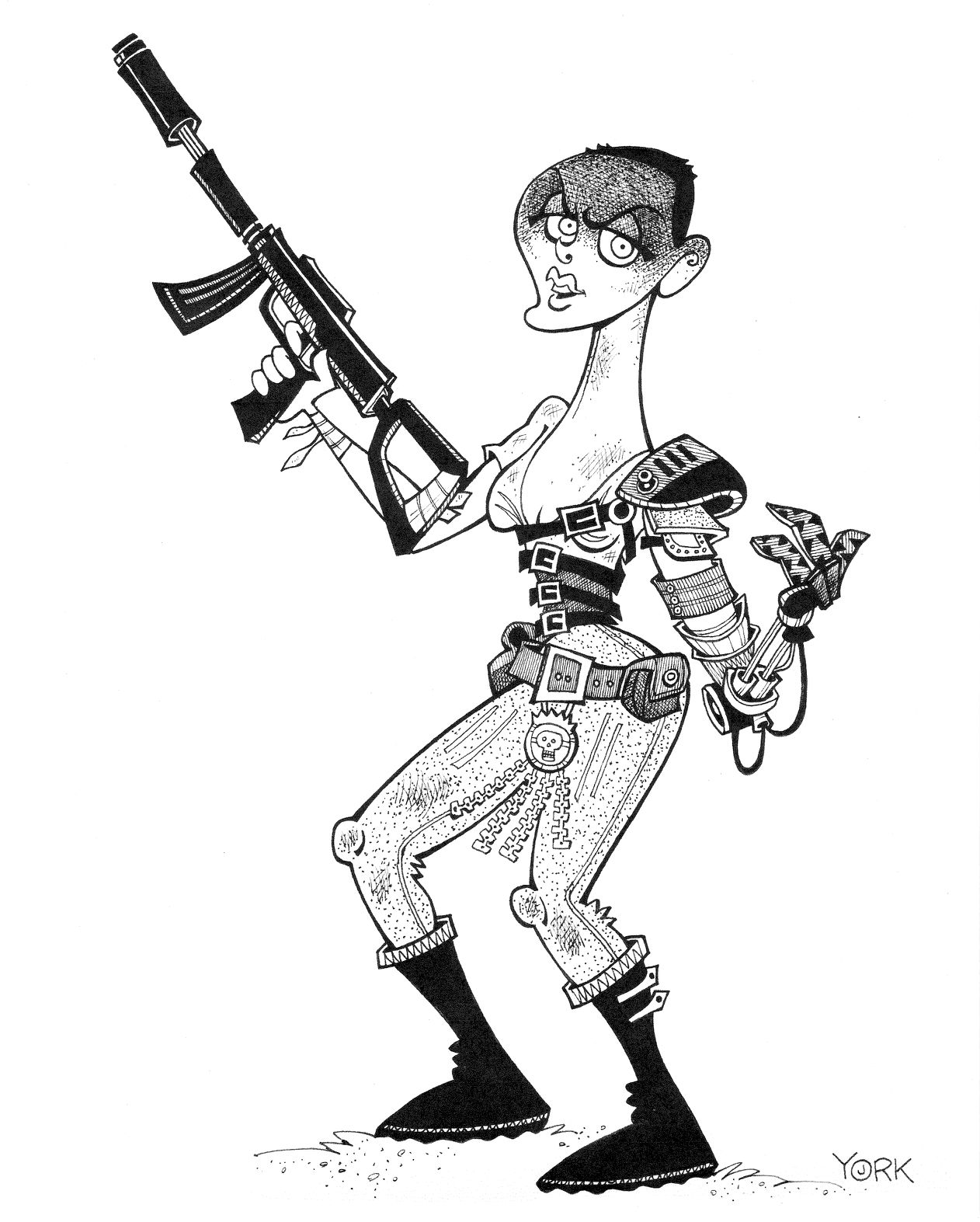

Another example of a sequel mixing things up yet still succeeding by keeping the core essences in every frame is the aforementioned Mad Max: Fury Road. Helped by the fact that it was helmed by original creator George Miller, the film kept the Mad Max essence despite moving him as a character into more of a supporting role here. Indeed, the true lead in the third sequel was Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron). She assumed the mantle of helping a group of vulnerable people escaping the control of a vicious, post-apocalyptic authoritarian, just as Max had done in the previous two sequels The Road Warrior and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. The plotting was similar, but more importantly, so was what the film was about: revenge.

In the original Mad Max, Max is a disillusioned cop who turns to vigilante justice to exact revenge against the psychotic hoodlums who killed his wife and child. In Fury Road, Furiosa is a disillusioned enforcer for the overlord Immortan Joe who rebels against him and his hoodlums by stealing Joe’s abused wives. Yes, both films have a lot of car chases and little dialogue, and a world-gone-to-hell mood, but the essence remains that of revenge. And if anything, it’s more justified in Fury Road because Furiosa is a victimized female, too, one who in fact has been maimed and condemned to living life with a prosthetic arm.

Miller’s sequel didn’t make changes for change’s sake. Nor did he make the window dressing—the fast cars, the faster editing, the gonzo characters, and over-the-top action—the whole kit and kaboodle. It’s all that, but it’s still a classic revenge tale, only here Max supports Furiosa achieve her goals because he’s been there and done that as well in a previous life. The Mad Max franchise stayed on brand, clinging to its recognizable style, but more importantly, striving to keep true to its genuine story of revenge.

If only more sequels worked that hard to get it all right. I can count the truly sublime sequels to intellectual properties in the past 30 years on two hands and still have enough fingers left over to bowl. Still, when the lights go down in the theater, I’m always hopeful that a sequel will rise to the challenge of making more out of its task than just being a quick money-grab or a sequel about surfaces. Those writing sequels face a lot of obstacles, but it helps if they understand what’s really going on in the story they’re trying to build upon.

And who knows? Maybe the producers behind Paranormal Activity can reboot it knowing full well that their franchise doesn’t need those psychotic siblings. Psychotic ghosts are more than enough, as long as you have a camera.

*Feature Image: Furiosa by Jeff York