Are Studio Heads Nuts?

Decades ago, I interviewed for a job at Disney’s in-house ad agency in Orlando. I turned it down for many reasons, mostly because I heard rumors that the account would be transferring to Leo Burnett within six months.

That turned out to be true, but one other matter gave me pause too: Disney CEO Michael Eisner’s management style.

I was told by everyone there that he was the final word on everything and had strong, not-to-be-questioned opinions on everything from the gift shops to the elevator music to the carpeting and drapes in the Contemporary Resort. I loved what Eisner was doing for the movie industry—he gave us The Little Mermaid, and the Disney animation renaissance—but even at my young age back then I knew his micromanagement style was a no-no that would be a problem when it came to seeing the forest for the trees.

Granted, Eisner was a pretty terrific CEO, but one wonders what else he might’ve done if he had trusted more people and not wasted his time thinking about drapes. Still, what is it with studio heads that drives them to seem so obsessive, indeed, more than a little crazed? If anything, studio heads are even more “out there” today, demonstrating destructive behavior far more egregious than wasting time on drapes.

Most studio heads did themselves no favors during last summer’s WGA and SAG strikes. As if they weren’t already despised enough for meddling or overreach, most of them went wholly on the record, wanting to deny the lifeblood of Hollywood artists from making an acceptable living. And the studios had already gotten away with such chicanery as they hadn’t renegotiated writers’ and actors’ residual contracts since long before streaming and were getting away with not paying proper residuals for such repurposing for over a decade.

It really was wholly unethical, but most studio heads would tell you they were being good businessmen, keeping costs down.

They may have been keeping costs down, but such cost-cutting didn’t keep them from gifting themselves with ludicrously extravagant bonuses year in and year out. But then, studio heads have rarely been overly principled.

In the Golden Era of Hollywood, much of the behavior of studio heads was positively criminal. Back in the 30s and 40s, Columbia Pictures president Harry Cohn invented “the casting couch,” expecting sexual favors from the female stars he cast in his studio’s films. In the 70s, Paramount chief Robert Evans missed the cautionary memo about such as well, not to mention the brief that warned of the perils of drug use in the office. And with all the sins that Harvey Weinstein indulged in during his heyday in the 90s and early part of the 21st century, it’s amazing that he found time to market and promote anything, let alone Best Picture Oscar winners like Shakespeare in Love and The Artist. Fellow Shakespeare in Love producer, Ed Zwick, has a few things to say about Weinstein’s shenanigans in his new biography Hits, Flops and Other Illusions, only adding to the list of Harvey’s many sins.

It's always dangerous in Hollywood when egotists like Evans and Weinstein are so insecure that they feel the need to become the news as much as the films they’ve greenlit. Granted, any executive is going to attract press in such a high position, but too many head honchos get the ink for shenanigans that do not help their company’s cause or reputation. And today, it seems far too many studio heads are getting the worst kinds of headlines for too many decisions that seem immoral or utterly nuts.

Perhaps the poster boy for such inanity is Warner Bros. Discovery chief David Zaslav whose become one of Hollywood’s biggest villains in the past years due to his tendency to throw finished products into the vault never to be seen. Does that make more sense than releasing them vis a vis VOD at least?

I mean, the works are done, why not give audiences a chance to take a look?

Three of such victims included the WB films Batgirl, Scooby Doo Holiday Haunt, and Coyote vs. Acme. That last one seems especially egregious considering that the buzz about the film combining live action and animation concerning Road Runner’s favorite antagonist was deemed a big winner and potential big, box-office hit.

The movie tested very well during multiple preview screenings, but none of that was good enough to persuade Zaslav to release it. So, it sits in a vault, never to be seen? Even if he gets the tax write-off, where’s the standing behind the company’s creations? That part of the equation seems to have eluded Zaslav.

He's no newbie to show biz either, having acted as the CEO of Discovery since 2006 and held the top dog role of everything regarding Warner Media, too, after their merger with Discovery back in 2022.

But in addition to canceling many nearly finished projects, or keeping completed films in the vault to claim those tax write-offs, Zaslav has also pulled titles from the company’s streaming platforms to avoid paying residuals. Perhaps most ridiculously, Zaslav was the guy who decided to remove the HBO name from its streaming service, leaving just “Max.”

Why would any businessman with any sense of acumen denigrate a beloved and respected brand name in such a way? It’s so inept that Patton Oswalt felt the need to vilify Zaslav when he recently hosted the Golden Reel ceremony. There, Oswalt joked that Zazlav gave a three-picture deal to H & R Block. That’s a very funny line about an increasingly serious problem gripping the industry—disastrous decision-making in the C-suites.

Look, I understand that it’s called show business, not show art, but still, where is the show part in so many of these tin-eared studio exec’s equations?

Back when Hollywood was founded, producers, studio heads and the likes in power came from the theater world. Those who produced shows for the vaudeville circuit or the Great White Way were really showmen more than money men, and when they came to town to make movies, they led with their entertainment savvy, not their bean counting skills.

But since then, more and more studio heads and such executives have come from MBA programs, or at the very least, applied such bottom-line, Wall Street-style acumen to the entertainment industry. And it’s an uneasy mix at best.

Risk may be poo-pooed in most businesses, but it’s part of the game in the world of creativity and art. And if any CEO like Zaslav buried a product that tested well and cost his company hundreds of millions of dollars to create, he or she would be likely ridden out on a rail.

Show biz is more than an oxymoron, it’s filled with morons who don’t get that comparing a film or a TV show to a soda or carpet cleaner is apples and oranges at best. Profits aren’t always a given, and often very hard to calculate in Tinsel Town, especially when you really can’t be sure of how anything is going to be received until you actually put it out on the big or small screen and let a genuine public, not a test audience, discover it and pass judgment.

It was screenwriter William Goldman who once famously described Hollywood as a town where “no one knows anything.” The two-time Oscar winner understood that all of the prep, testing, and educated guesses put into a film or show don’t guarantee its success. Hollywood fare cannot entirely be judged until it’s put into the hands of an audience.

Consider Macauley Culkin versus Arnold Schwarzenegger back in 1990. Both had movies coming out that Christmas, but who would have ever guessed that an unknown child star would best the world’s biggest movie star at the box office? But that’s exactly what happened when his Home Alone kicked the ass of Arnold’s Kindergarten Cop. The latter film even received some of the best test scores in Universal Pictures history, too, but none of that was a substitute for the real paying public’s willingness to hand over their hard-earned dollar at the box office. And they chose the upstart that season. Indeed, no one really knows for sure what is going to happen.

The general thinking by those in the C-suite is that their first concern is the stockholders. They’re mistaken. It’s not; it’s the brand.

Not only is brand loyalty how William Holden’s furniture designer bested CFO Frederic March in their contention for the CEO job in 1954’s “Executive Suite,” but it should be the trump card in any business discussion. After all, investors can come and go, and often do, but the brand remains no matter.

But profitably has turned into cutting off noses to spite faces. Studio heads not only damaged their own reputations but the entire town when they worked actively against writers and actors trying to make a livable wage. The fat cats threatened them by proposing they’d hand over their jobs to A.I. and ChatGPT. People who think that such apps are artists, true artists, shouldn’t be running studios.

A.I. can replicate, but it’s called artificial intelligence for a reason. It’s building on what humans have made. It’s a Xerox at best.

Oh, and anything created, be it a film, show, podcast, print ad, book, song, or article, should not be described as “content.” Any studio head regarding them as slots on a chart, mere click bait, or blanks needing to be filled in, should be fired. Immediately.

How low can you go when it comes to ambition for art? Such goals aren’t just low-hanging fruit, they’re loathsome. The product needs to be the number one concern of any creator, and it should never be described so dismissively as content.

As somebody once famously said, you cannot swim for new horizons without the courage to lose sight of the shore. Show business requires risk, investment in both time and money, and faith. Not everything comes down to the dollar. And anyone working in artistic fields must refrain from sabotaging the process in favor of cutting corner.

Greed is not good when it comes to art.

The idea that we all need to accept that the only guiding principle in our modern world is the almighty dollar reminds me of the cynical philosophy of Arthur Jensen, the fictional CEO of UBS-TV in Sidney Lumet’s pungent 1976 dark comedy Network.

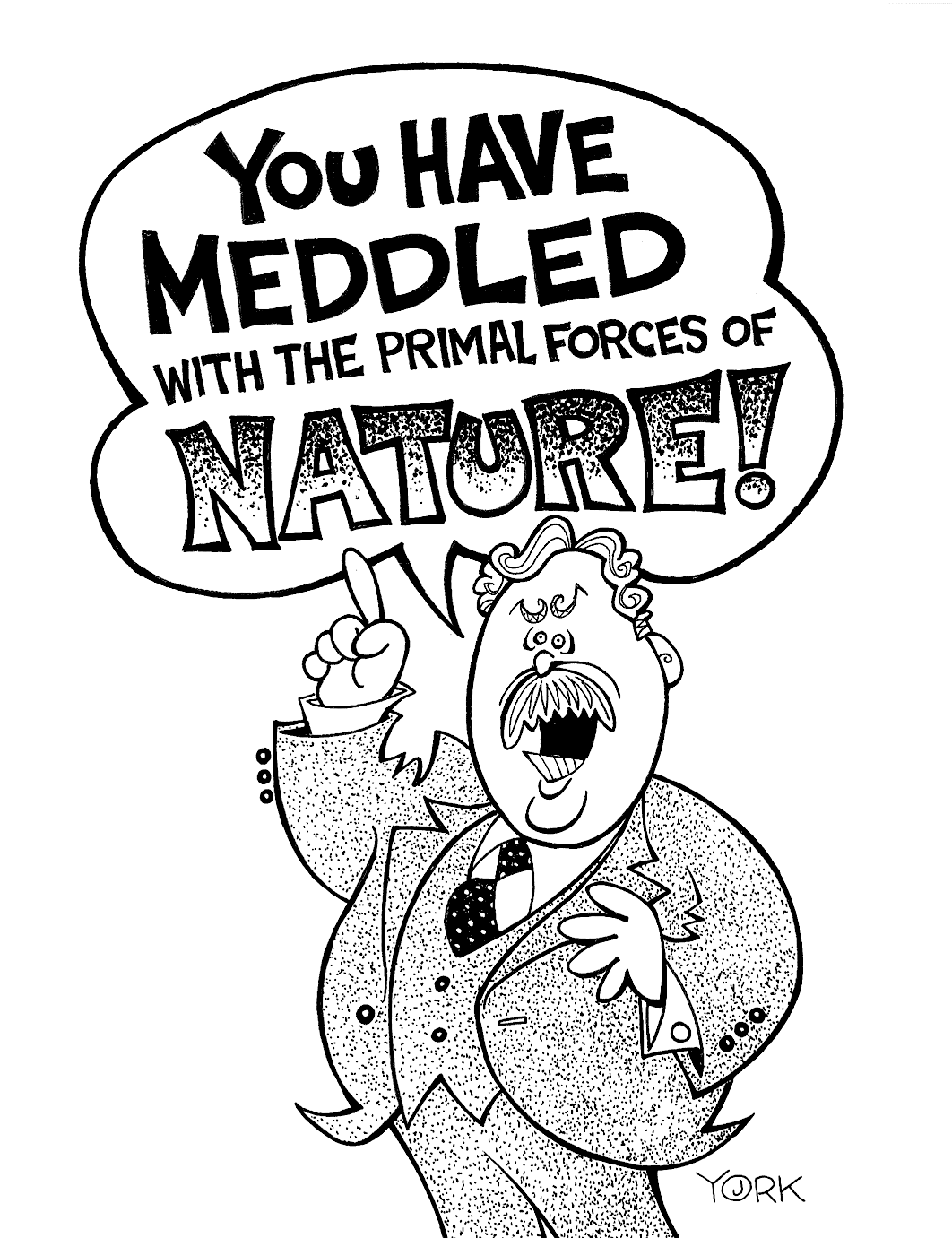

In that film, Howard Beale (Peter Finch) is a crazed news anchor who becomes a phenom due to his political rantings on TV. All is well, when the ratings are high and audiences are passionate, but then one night Beale indicts Jenson for his amoral greed and sneaky business practices out of the spotlight and Jensen blows a gasket. He summons Beale to his office where he harangues him about the ways of the business and how the dollar rules even the news division at UBS. It’s one of screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky’s most stingingly cynical monologues, and here is a truncated excerpt by Jensen:

"You have meddled with the primal forces of nature, Mr. Beale, and I won’t have it! … You are an old man who thinks in terms of nations and peoples. There are no Russians. There are no Arabs. There are no Third Worlds. There is no West … There is no America. There is no democracy. There is only IBM, and ITT, and AT&T, and Dupont, Dow, Union Carbide, and Exxon. Those are the nations of the world today."

Sure, dollars matter. But so do lives. So do artists. So do their creations. Films should be seen, not tucked away in vaults due to one tin-eared executive’s discretion. Shows should be given a chance to find audiences. And not everything can be proven by testing.

And a good studio head needs to concern themselves with truly pressing topics. Amongst them?

Safeguarding their products from copyright infringement, piracy, and yes, A.I. fakery. Finding original content. Encouraging diversity. Fighting censorship. New distribution channels. And making sure film history isn’t lost.

The more studio heads realized such things, where their real responsibilities lie, what the job really demands, the better they’ll be at doing their jobs. Who knows, they might even be worthy of those Herculean bonuses they keep rewarding themselves with, year in and year out.

But then, as Goldman said, no one knows anything. And that is certainly true of far too many calling the shots in Hollywood.

*Feature illustration by Jeff York