Art vs. Artist vs. Optics: Why We Wrote a Slapstick Comedy About Race, Even Though One of Us is a (Gulp) White Guy

Foreword

by Cristian Duran (A Person of Color)

If you’re white and you’re reading this, I hereby grant you permission to unclench your asshole.

Signed,

A POC

Over the pandemic, one of my closest friends, Cristian Duran, and I wrote a feature comedy called Race: The Movie (it’s about race).

It's a screwball parody of all of the recent Oscar-bait race movies: from those of the white savior ilk—think Green Book, Hidden Figures, The Help—to those of the more prestigious variety—Moonlight, 12 Years A Slave, Black Panther.

It features:

a white protagonist named Wyatt Saveyer,

a black protagonist named Gene Yus,

a plantation-owning villain named Ray Cist (and his wife Ovarian),

their Brooklyn-residing daughter named Jenn Trifier and her namesake land trust company (Jenn Trifier Realty),

a wizened, advice-bestowing African-American custodian named Magic Black,

a Black-Panther-style king named T’Challa-Latte,

a black bounty hunter named D-Jango (the D is pronounced),

a cartoonishly racist overseer named Max Hayte,

A …

You get the idea.

In short, it’s really, really, really silly.

Now, I’m a white guy. No one has ever looked at my face and gone, “I wonder what race that fella is.” I have a face so Caucasian that it looks like it could’ve been on a popcorn ad in the 50s.

And if you’re wondering what race my co-writer Cristian is, you’d be like just about every person we’ve pitched the movie to or told it about.

Our first joke of the script tackles this:

To be clear, I don’t blame or begrudge anyone for wondering this. Race is certainly—and justifiably—something that is taken very seriously, and curiosity/concern over the identity of the writers can be a way for people to know the comedy comes from a good place and is underscored by a depth of thought, understanding, and experience that (on racial issues) white people are less likely to have. Race is obviously not an impeding factor in the lives of us Caucasians.

Whenever I tell people about our movie, the first thing I have to say is, “Don’t worry, my co-writer isn’t white.” Only then will people let their guard down and allow themselves to enjoy any of the gags, jokes, and satire from it.

In other words, his identity gives them a license to laugh.

Cristian and I have long joked that if our movie gets made, I’ll be the one people will get mad at. I mean, look at me: I’m the picture postcard example of white privilege, and—for some—even the thought of a fella as white as me making light of issues as sensitive as these ones will be a bridge too far.

But that’s a mentality Cristian and I couldn’t disagree with more. The way you can take the power out of something is by being willing to make fun of it. When you quarantine a subject away from the shedding-light-on-the-truth nature of jokes, you both protect that subject and give it greater power.

Jokes can be a weapon disguised as entertainment. And because of their disarming nature, they can be more effective in demonstrating a point about inequality, prejudice, or oppression than a serious speech or dramatic monologue. If you can get people laughing, you can get their guard down. And once you get their guard down, you can convince them of a reality they may not have bought into before.

Take one of my favorite scenes from Race: The Movie, which I think has one of our tentpole gags. For basic context, our protagonists—three black guys and one white Italian guy—are basically trying to get back to Kawanda to save the day when they are pulled over by a bike cop (yes, it’s anachronistic).

On the surface, it can seem offensive to have a character tell black men they are “3/5ths of a person,” but also: this was an undeniable reality of America. The 3/5ths Compromise was a real bill passed by Congress to determine how much of a "person" black people should count as in determining a state’s population for tax purposes.

In the course of writing our movie, a screenwriting friend of mine (one with vastly more experience/success than me) told me that the movie would be more likely to be made if we omitted the N-word from it. Producers, he said, are less likely to greenlight something with that word.

In many ways, I understand this impetus. It’s the most disgusting and vile word in the English language, and it’s important to be respectful of this fact.

But can you imagine how dishonest a movie about race—especially a period comedy—would feel without it at all? That would be a form of whitewashing. If we are going to face America’s dark past, then let’s face it: we had a dark past. And that was like, the fourth most used word in the English language during that era.

(FYI, let the record show that any use of the N-word in our script was in fact typed by Cristian.)

Doesn’t it feel a bit cheap whenever screenwriters have their most racist characters use other, less offensive slurs for black people? Like, the point of a slur is to be maximum demeaning and disrespectful. A racist character wouldn’t think, “I want to be racist, but I mean c’mon it’s 1950, get with the times.”

In any case, this fear to me strikes to the core of one of the problems with modern comedy: it’s really self-conscious.

Many comedians are afraid of being deemed an immoral or bad person based off of their jokes, and I want to be clear: this fear isn’t the worst thing. Good comedians, in my eyes, should be empathetic, and comedians with a concern for how their jokes come across are attempting to be empathetic. This is obviously not a bad thing, and the contingency of comedians with a flagrant or even proud disregard for the ever-evolving social mores of our society can be toilet-bowl terrible or uninteresting.

But, often, the comedians who are hyper-deferential to hyper-sensitivity are writing and making uninteresting comedy because, at their core, they’re being self-conscious.

Wokeness is not killing comedy. Self-consciousness is.

I say that because, in my eyes, the best comedy should feel and be joyful. Was Blazing Saddles a masterfully-satirical and thoughtful send-up of race and racism in America? Absolutely. But at its core, it felt joyful. It felt fun.

Same with all the best comedies.

Austin Powers. Borat. Airplane. Naked Gun. Monty Python.

The makers of them were all expressing themselves fearlessly joyfully.

The reason slapstick is my favorite form of movie comedy is because, at its base, it’s the most vulnerable.

Do the characters wear silly costumes, have goofy voices, and say dumb jokes? Yes. But to me this willingness to look stupid is what vulnerability in comedy looks like at its purest form. It's the manifestation of freedom from judgment—from oneself and from others.

So at the risk of being pretentious (and let’s be honest, this is a thinkpiece which is inherently pretentious), that’s why Cristian and I wrote Race: The Movie (it’s about race).

We wanted to write something that was sharp and silly, smart and stupid, heady but with broad appeal, playful yet critical, joyful but with a conscience, a big technicolor comedy that explored the black, the white, and the grey, and we wanted to do it with throwback slapstick updated to fit our modern conversations, conventions, and culture.

We were annoyed by the way much of Hollywood handles race in its movies, which almost always feature condescendingly obvious messages that brush over portraying actual oppression in service of making the audience feel warm and fuzzy inside—and usually feature deliverance from the moral-authority white character.

So, rather than merely complain about it on Twitter, we decided to fight art with art and write this movie.

In the course of circulating our script, perhaps our favorite piece of feedback was from a producer who rejected it because “it’s just too much of a hot-button topic right now.” Imagine that.

Race. Too much of a hot topic right now.

By “right now” do you mean for, you know, all of time?

Hopefully, we’ll be able to check back in with him after a couple weeks—once this whole race issue dies down.

If you’d like to read the script, request.

If you’d like to be a part of our movie, get in touch.

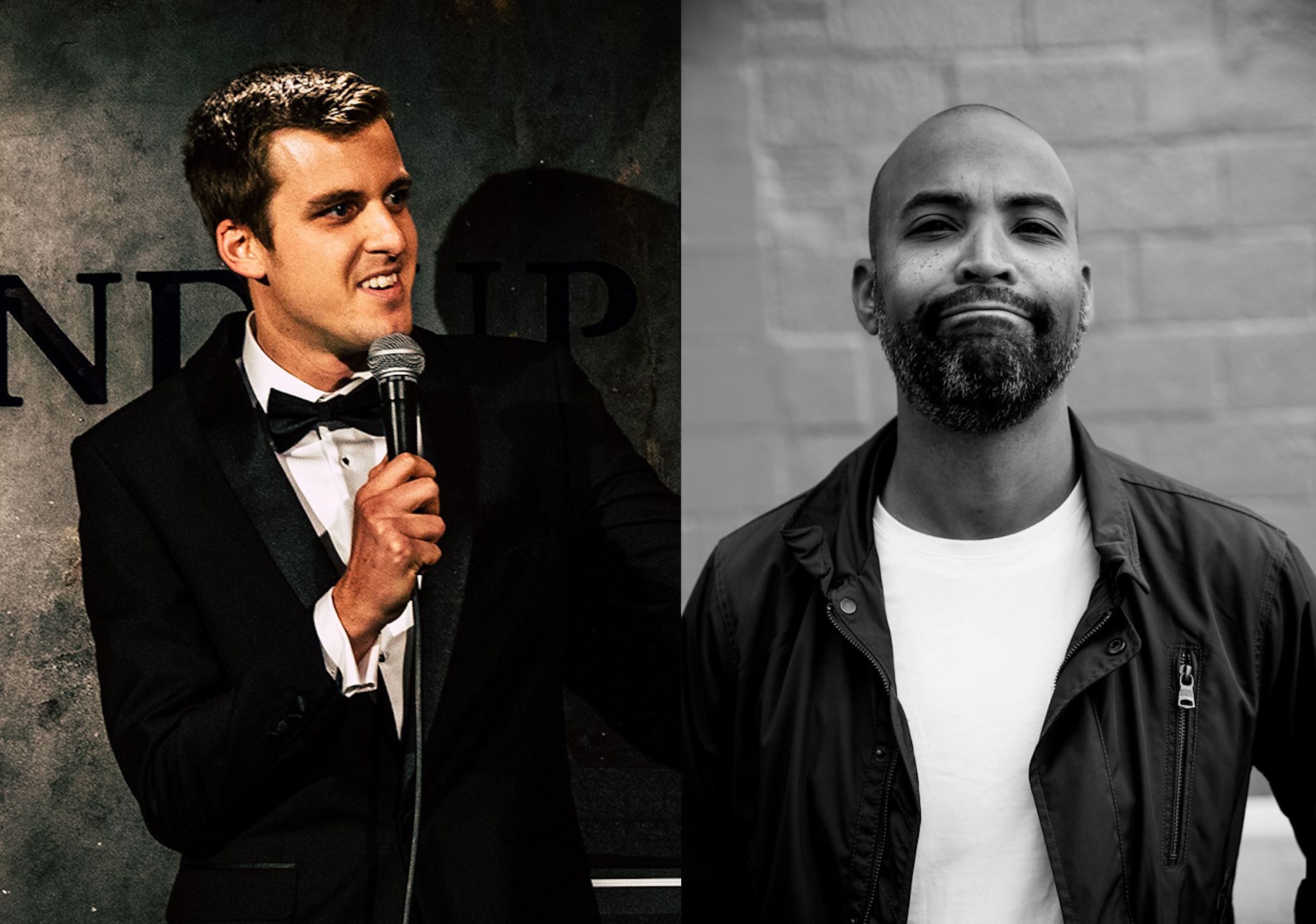

*Feature Photo: Bret Raybould (left) and Cristian Duran