Dear Diary: A Return to Journaling

April 22, 2022. I am writing this from my living room. I left the office 784 days ago, expecting to return in two weeks. I didn’t empty my snack drawer. I think I forgot to clean out my coffee mug. I seriously regret leaving my ergonomic keyboard behind.

I’ve been told several times that I should prepare to return immediately. This time we’ve been pushed back until June. I cancel my parking pass again and consider getting a tattoo.

I really need to wash that coffee mug.

My unvaccinated child went back to in-person classes a few months ago. He’s now quarantining at home after being exposed in the classroom for the third time. They won’t tell us what happened to his teacher. I spend my days trying to swallow the lump in my throat and focus on how excited he is to be back with friends again.

I should probably throw the mug out.

I used to journal a lot in college. It was a way to process all of the complex emotions of growing up and finding myself. Eventually, life got busy and I found other outlets. Journaling seemed too melodramatic and silly for a mature professional writer like myself.

Then, 700 days ago, it became my life preserver.

While the world was learning to bake banana bread, I chose to write love letters to my friends and family. It was an act of opening my heart in rebellion against total social isolation. It began as a personal exercise, an uncensored lovefest only I would see. In my morbid fantasy world, after COVID took me, they would eventually find my last words and distribute them to their intended audience.

Then the crematoriums started to run 24/7. There was no guarantee that any of us would make it out of this alive.

There was no time for ego. No time, period.

I sent the letters.

Melissa

“Life is too enormous to fear.”

Journaling is not just penning diary entries. It is an active analysis of one’s own emotions, and can take almost any form: a poem, a screenplay, lyrics, letters to a ghost. In this case, what began as journaling became correspondence—final words to hold onto if I didn’t make it through.

Reaching out to other pandemic journalers, I found they used all kinds of media to cope with the unprecedented.

What follows is a series of excerpts from those journals. I asked each person to choose their most important entry, and to provide as much or as little explanation as they wished. These are the raw responses of writers, preserved in amber, to the most emotionally taxing moments of the past two years.

Some are conceptual thought poems. Some are direct transcripts of life events. Some are crumbs. All are gifts.

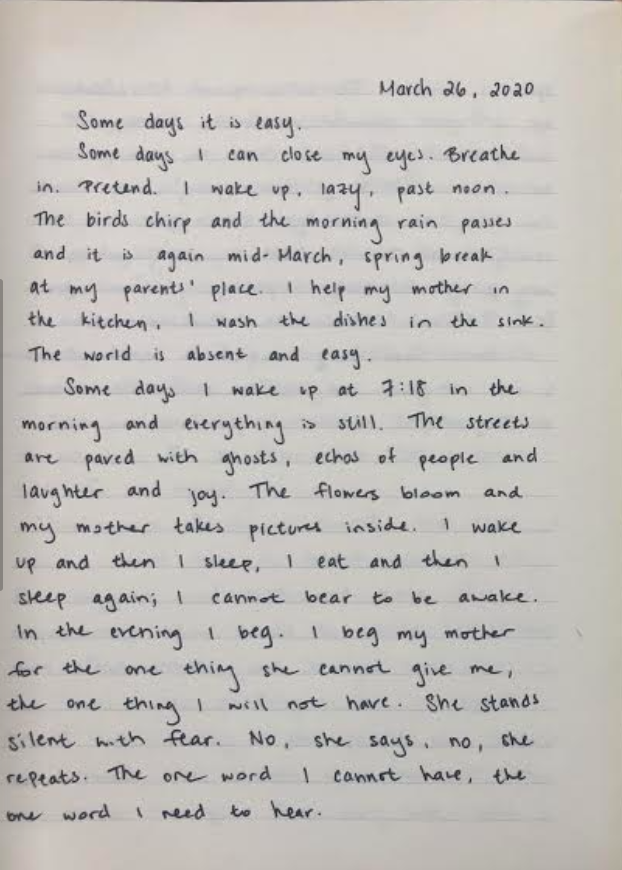

Anonymous

(Day 1 of lockdown in U.S.)

Mara

"‘Are you sure you know? Or are you just guessing?’ ... ‘I know’, I lie.”

In these early days, there were few resources to manage the overwhelm, or to grapple with mortality constantly breathing down our necks. Amid such extreme ambiguity and fear, caregivers trusted journals to keep secret what we couldn’t share with our families—that none of us knew what was going to happen—so we could put on a brave face and say, “everything will be alright”—even as “alright” felt like a foreign concept.

Journals provided us a way to acknowledge the chaos of the unknown so we could provide stability for our loved ones.

On the other side of fear lies courage. These next writers used journals to express their desire to get to the other side through courageous acts.

Phil

“IOU”

Casey

“The Probably Okay”

For some, journaling is a form of meditation; for others, resistance. Phil translated his personal experience as a funeral worker into a screenplay. In his story, the characters perform an act of radical love that he implemented in real life as a way to comfort the aggrieved. Phil handed out IOU’s to communicate the message that in the future, the distance will not be so great. We will be able to fully love one another again. Casey turned his amplified sense of doubt into a glass half-full approach to pursuing his career goals. An embracing of self-reliance.

But journals can also support our need for connection during a time when safety means pushing others away—the very literal regulation of our interactions, bodies, and emotions.

Jean

“Streets paved with ghosts”

Laura

“Lucy had come to the Buddhist wellness spa to die.”

These entries capture a specific moment in history; one we can look back on, recognize shared experiences, and gain perspective from the vulnerability of others.

Jean and Laura captured the melancholy of isolation in story-poems. The next writers, each survivors of their own tragedies, urge us to solidify our purpose, love ourselves, and appreciate the gift of life.

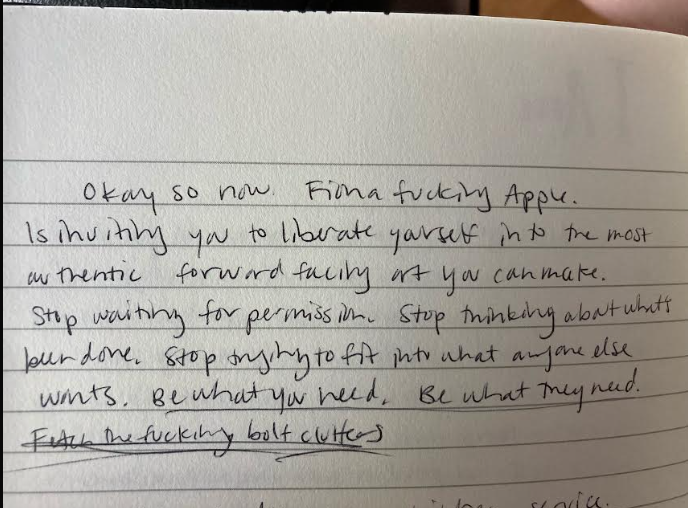

Kate

“Fetch the fucking bolt cutters”

Christa

“With time, what happens to us becomes what something that happens for us.”

While restricted from exploring our usual mediums, journals helped many artists engage with hardship on the page, and became powerful outlets for raw creativity to flow. Journalers across the world, writing only for themselves in isolation, inspired strikingly common themes: push yourself to “do something,” see the good, drop fear, and reach for personal goals. Even as we labored alone, we were united in hope.

Day 784 is crowned by an audacious California sunset. What was once unprecedented is now being billed as The New Normal. Truly, some things are better. I enjoy working from home. I’ve found peace in solitude. There are more snacks here. I’ve acquired new mugs.

Though still swimming in ambiguity and a heightened sense of anxiety, whose impacts I won’t fully grasp for a long, long time, I am reminded to push through the silly insecurities that previously plagued me, and to live boldly.

There are much greater things to fear than rejection. I am driven to make more of what little time I have on this planet.

I smile. There is still time.

*Feature image by okalinichenko (Adobe)