Four Women-Written Albums That Revolutionized Music

When I pitched this story at the very end of March, I knew the article wouldn’t be published in the remaining two days of Women’s History Month. But having seen so many groundbreaking women featured during the month, I contemplated how backwards it is to celebrate the accomplishments of women for only one month out of the year. If, due to misogyny, women have been excluded or downplayed throughout the decades, then we should work to ensure that they are heard—primarily because it is the right thing to do: creators deserve credit for the amazing things they have done.

However, spreading the word about these artists helps everyone, everywhere.

Women have influenced music throughout history—if they’re excluded from the narrative, then we will never have a true understanding of humanity’s current place in the world.

As a musician, I will always appreciate the artists who inspire me, and I wanted to appreciate some of my favorite albums written by women.

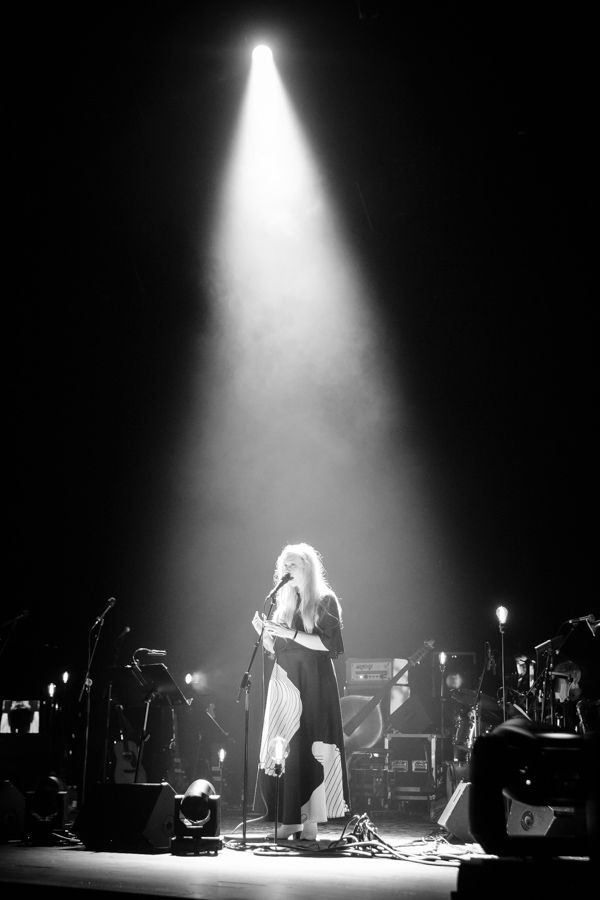

Hejira (1976) by Joni Mitchell

The word Hejira references the prophet Mohammad’s migration from Mecca to Medina in 622 AD. Joni Mitchell defined it as "running away, honourably." She wrote Hejira while on a solo road trip from Maine to Los Angeles. Between the clean electric guitar tone you hear on the album, Joni’s tranquil voice, and lyrics which embody the scenery and emotions of her travels, the album has a mysterious, windswept feel.

In the song “Amelia,” Joni likens herself to Amelia Earhart, singing that Amelia was “a ghost of aviation / she was swallowed by the sky / or by the sea like me she had a dream to fly / like Icarus ascending.”

The songs “Refuge of the Roads” and “Blue Motel Room” further cement the album’s theme of travel. Through “Coyote” and “A Strange Boy,” Joni explores topics of identity and relationships.

My favorite song on the album, both musically and lyrically, is the title track, “Hejira,” in which Joni contemplates her existence, saying, “Well, I looked at the granite markers / those tributes to finality, to eternity / and then I looked at myself here / chicken scratching for my immortality.”

Joni started singing when she contracted polio at age nine. She spent Christmas bedridden in a hospital, so she decided to sing carols to brighten the mood of the patients around her. This experience introduced her to her love of performing.

However, it also interfered with her music career. The disease affected Joni’s hand strength, which hindered her ability to form conventional chords. Nevertheless, she adapted by experimenting with the unusual guitar tunings, which contribute to her unique sound.

Her venture toward the avant-garde didn’t end with tunings. In albums like Hejira, Joni broke out of folk and pop boxes. She pushed her songwriting to new territories, crafting eccentric, jazz-inspired music. She utilized complex song structures, unorthodox melodies, and surprisingly minimal percussion.

For Hejira, she teamed up with notorious jazz bassist Jaco Pastorious, who added his haunting, soulful playing to the mix. Mitchell said in a 1979 interview that “if you change, they’re going to crucify you for changing. But staying the same is boring. And change is interesting. So, of the two options, I’d rather be crucified for changing.”

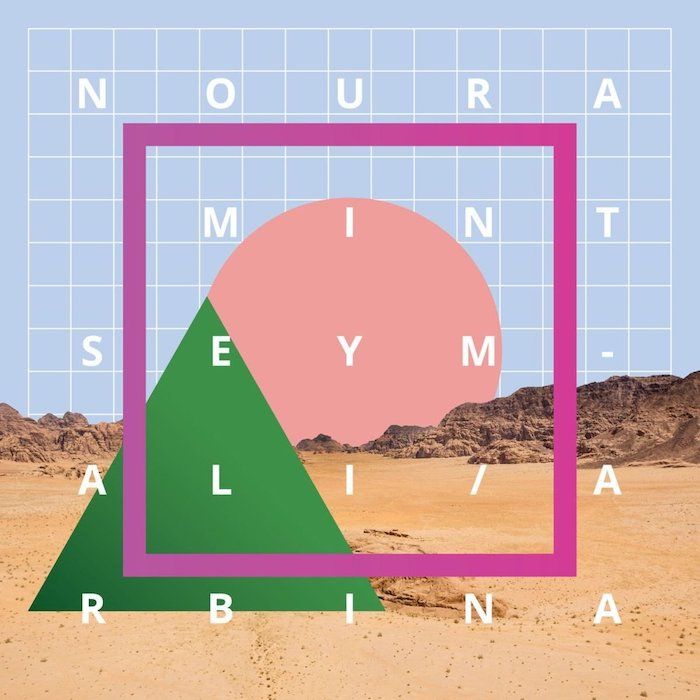

Arbina (2016) by Noura Mint Seymali

With her Moorish fusion music, Noura Mint Seymali aims to make the Mauritanian sound more accessible. Born into a family of West African griots, Noura grew up surrounded by music. Seymali’s grandma, Mounina, taught her how to sing and play the ardin, a nine-stringed harp played exclusively by women.

At age 13, Seymali started touring as a supporting vocalist with her stepmother, the renowned musician Dimi Mint Abba, who was dubbed the best singer in Africa by none other than Ali Farka Touré. Her father, Seymali Ould Ahmed Vall, invented the first Moorish melodic notation and wrote the Mauritanian national anthem. He encouraged Noura’s love of fusion music.

In a 2016 interview, Noura reflected that “growing up in a griot family ... is not an obligation but an opportunity” and that she had “profound support to pursue music.”

The Islamic Republic of Mauritania is home to a rich diversity of cultures, including the Arabic Moors and the Tuareg, Wolof, Berber, Somike, and Pulaar people. The convergence of so many groups of people gives Mauritania a particularly rich tradition of music. Noura Mint Seymali said that “many people have absolutely no idea about Mauritania or our music,” so she wants to make their music “known to the world.”

In this, she’s already succeeding.

Her band tours both locally and internationally. Arbina earned a #1 on World Music Charts Europe and a #1 on the Transglobal World Music Chart. Their previous album, Tzenni, won “Best Female Artist in North Africa” at the African Union’s 2014 All Africa Music Awards.

Noura Mint Seymali formed her quartet in 2012. She started the band with her husband, Jeich Ould Chighaly, a musician who translated the phrasing of the traditional tinidit to a modified electric guitar, and who adds a psychedelic flair to their songs. They enlisted the talents of Ousmane Touré, who worked with Seymali’s father, and who is widely regarded as one of the best bassists in Mauritania; as well as drummer/producer Matthew Tinari, from Philadelphia, USA, who met the band at a festival in Senegal, fell in love with the music, and adapted the role of the typical percussion, the t’beul, to a drum set.

Highlights of Arbina definitely include “Ghlana,” with its cool, almost confrontational guitar line. The opening song, “Arbina,” showcases Noura Mint Seymali’s impressive ardin playing and its vital role in their music. “Tia” has a really interesting introduction, and it demonstrates the band’s ability to own a more laid-back song.

But the whole album is a masterpiece. The band’s music carries a swaggering sense of rhythm—hard enough to rock, but not so fast that they sacrifice their emotion. Their melodies are as original as they are powerful. The intricate trill of Seymali’s ardin harmonizes perfectly with the other instruments. And, in every song, Seymali’s fierce and beautiful voice is the focal point, seizing your attention and tugging at your heart.

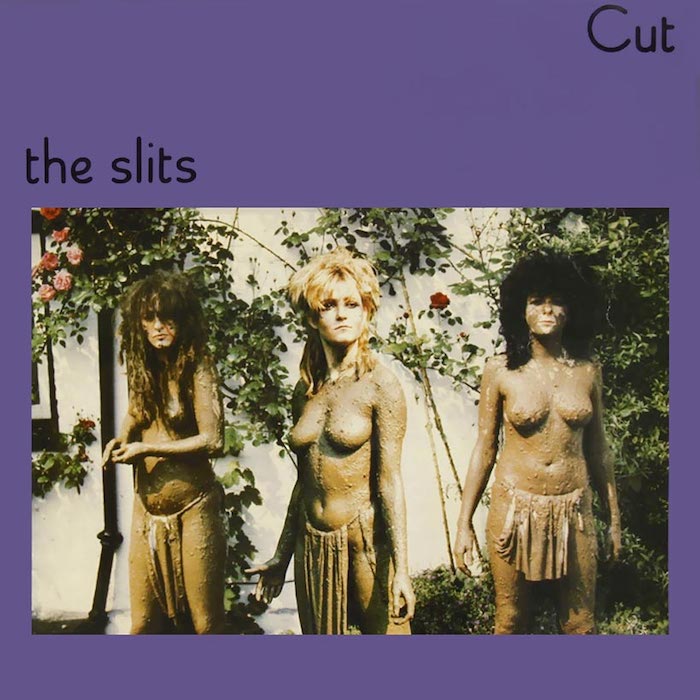

Cut (1979) by The Slits

The Slits incorporated music styles from reggae to dub, but they’re as punk as you can get. The founding bandmates met at a Patti Smith concert, decided to form an all-girl punk band, and wasted no time before diving into the music scene.

True to the movement’s DIY mentality, they went on tour with The Clash before they could even tune their instruments, and they had been playing for only a little over two years when they recorded their first album. But when you listen to Cut, it is the band’s creativity, not their inexperience, that catches your attention.

The Slits incorporate a lot of negative space, which gives them a cool detached attitude, but the songs never feel empty. Tessa Pollitt’s catchy baselines bind the songs together. Guitarist Viv Albertine attacks her guitar with the perfect balance of melody and dissonance, of tasteful playing and punk abandon. Vocalist Ari Up punctuates their rebellious, sarcastic lyrics with howls, coos, and shrieks. Even their percussion is experimental—they added materials like spoons and matchboxes to the beats.

Everything about the band defies expectations. Of course, stylistically, they expanded the domain of punk music. Their album cover subverts traditional imagery of femininity by featuring the band members nearly naked and covered in mud, wearing defiant expressions. The band name, the Slits, reclaims a derogatory term used towards women. The band’s existence itself, as an all-women punk band at a time when the music scene was extremely male-dominated, is rebellious.

My personal favorite Slits song: “New Town” because of how unusual it sounds. And the band’s cover of Motown classic “I Heard it Through the Grapevine” is excellent because of how the Slits managed to retain the soul of the song while dissolving it into their art-punk style.

But I would most highly recommend their song “Typical Girls,” which not only is the most accessible song on the album, but also epitomizes the band’s feminist attitude, mocking the stereotypes that “typical girls ... don’t create / don’t rebel / have intuition / don’t drive well” before challenging the listener, “Who invented the typical girl? / Who’s bringing out the new improved model?”

Gospel Train (1956) by Sister Rosetta Tharpe

I could never write this article without celebrating Sister Rosetta Tharpe—she changed the face of music forever. Tharpe is known as the “godmother of rock and roll” because she preceded and influenced seminal rock musicians like Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, and Little Richard. She pioneered a new genre of music while battling the racism and sexism of the systems around her.

And she rocks.

Born in Arkansas in 1915, Sister Rosetta Tharpe grew up in a family of cotton pickers and evangelists. Her mother, Katie Harper, was a preacher and singer for the Church of God in Christ. Tharpe started learning the guitar when she was four years old, and at six, she began performing with her mother in Southern churches.

After honing her craft—combining Delta blues, jazz, and gospel music into her radical new sound—she moved to New York. She performed with some of the most famous musicians of her time, including Duke Ellington and the Dixie Hummingbirds.

At 23, she snagged a record contract and became wildly popular.

Today, Tharpe is criminally underrated. She’s not a household name unlike many of the musicians she influenced. Even though she essentially invented rock, she wasn’t inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame until 2018. She wasn’t obscure during her lifetime—25,000 people attended her third wedding and watched her perform—but has likely been delegated to the margins of music history because of prejudice against Black LGBT women. Woman guitarists were unheard of during her time, and critics of Tharpe complained she “played like a man.” (Her response was that she played “better than a man.”)

Within the industry, Tharpe was open about her relationship with gospel singer Marie Knight, with whom she wrote the song “Up Above My Head.” In the 1940s, the two toured together and seized control of their business decisions. Tharpe faced further pushback from even her religious base because of the stigma against combining gospel music with secular music.

In lyrical content, she straddled both worlds. She performed in churches and in nightclubs, so she stood out in both. Tharpe wasn’t afraid of going against the norm.

Regardless of her optimism, she still had to contend with the prevailing institutions of racism. Jim Crow laws were still in full effect. When performing with the Jordanaires, a band of white men, Tharpe had to sleep in a bus because she was barred from sleeping in their segregated hotels. While on tours, she had to get food from the back of restaurants because they didn’t let her inside.

Despite this, she persevered.

I love watching footage of Sister Rosetta Tharpe shows. There’s something surreal and wonderful about watching a black-and-white video of someone stepping out of a horse carriage to play a modern rock song. Armed with a Gibson SG and a vibrant voice, Tharpe creates brilliant, tasteful song compositions permeated by her passionate guitar shredding.

She’s an incredible performer. Usually donning an elegant dress and an elaborate hairstyle, she dances in place while she plays, her voice aching with passion so genuine that anyone who listens will know that she has lived her songs. She always looks like she’s having a lot of fun, which is something that I wish more modern rock musicians would allow themselves to express.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe revolutionized not only the music world, but also the culture that dictated who was allowed to participate in it.

Acclaimed guitarist and songwriter Bonnie Raitt said that Tharpe “has long been deserving of wider recognition and a place of honor in the field of music history” and that she “blazed a trail for the rest of us women guitarists.”*

*Feature Photo: Joni Mitchell / photo by Tore Sætre, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons