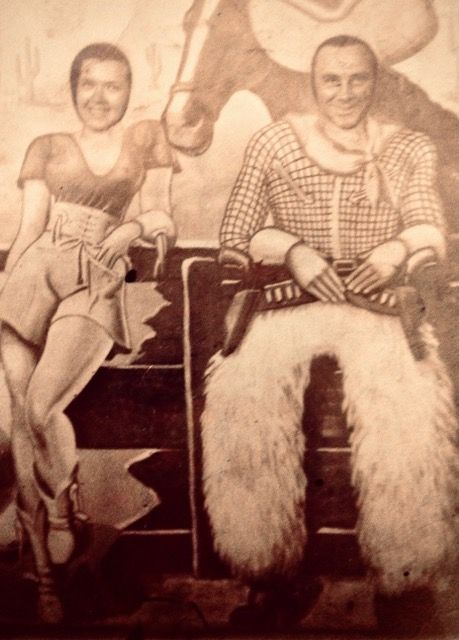

Fuzzy and June

Face facts. Grandpa told lies. Little ones. White ones. Half-truths. How much you pay for that Ford, Fuzzy? his friends would ask him. He'd say a thousand when it was really two. Lies like that. He told his friend, Mule, he got laid more than he did—but that was men's type of lying. About the biggest lie he'd told up 'til now was that it didn't matter to him that Grandma June was deaf. From the look on her face, I bet she's wondering if it was all lies—bet she's trying to figure out who that man is looking so clean and nice in that coffin over there.

It don't smell like most funeral parlors—no formaldehyde or nothing. Riley does a good job—he should for what he charges. I swore after seeing Ray in his Costco casket, I'd never look at another dead body ever again, but Mom said Grandma shouldn't be alone at the viewing, so here we all are. Funeral's in one hour over at the church in Spurger, and even though the day just started, I'm ready for it to be over. Can't wait to get back to the house, take off my pantyhose, and eat some of that food the church ladies made.

Can't wait to tell you all about it, Ray.

I wish you could see what me and Mom and Uncle Butch are watching right now. Grandma’s up near the pulpit, leaning over the open coffin, fussing with Grandpa's tie and shaking her head—like it's his fault it's crooked. Now she's working her way down to his shirt cuffs, but she knows not to touch his skin. Riley said it might tear, and God knows I don't want to see nobody's torn skin, so I'm staying right here.

Mom is walking to the front and trying to get her to her seat, but Grandma wants to sniff the wreath of red carnations the Rotary Club sent. She’s telling Mom that Fuzzy had a red carnation in the buttonhole of his white dinner jacket the night they met. Mom pretends to smile and says, “I remember.”

To hear Grandma tell it, she went to a county dance with a boy as a favor to his sister because deaf girls didn't get out much. Grandma says the boy started getting all friendly-like, so she excused herself to the restroom, and on the way, she ran into Fuzzy. She saw him, and he saw her—and the fireworks went off. She thought he looked perfect. He asked her to dance.

Their first song was "The Waltz You Saved for Me" by Wayne King. Grandpa held her close, cheek to cheek, and when he hummed along, she says the vibration made her whole body shake. When the band switched to swing, she kicked off her shoes to feel the beat through her bare feet, and that was when he finally realized Grandma June was deaf. Like a gentleman, he took her hand and led her through a few easy steps, and when the beat picked up, she followed him with perfect coordination. Those country folks had never seen the Jitterbug before, and it must have seemed like sex or something, because soon, everyone on the floor stopped dancing and cleared a circle around them … and watched.

He asked to drive her home, and because Grandma sized people up by their actions instead of their words, she knew she could trust him. On the way, he parked by the lake, and right there under the moon, he proposed. When I asked how she knew if she couldn’t hear, she said the moon was full, so she could read his lips. He sealed the deal with the red carnation from his buttonhole, humming their waltz into her ear, which she said sounded like thick gravel syrup and made her lady parts quiver. Grandma was deaf, after all, not dead.

OK, here comes Preacher John and his fat wife, Faye. He’s squeezing Grandma’s hands with his stubby, puffy ones, saying Faye’s gonna have to skip the funeral for her doctor's appointment in Jasper. Seems her sugar diabetes is getting out of control, and they’re worried. Hey, I got an idea—how about you two lay off the Twinkies and see what happens? Forgive me, Lord. I'm just edgy, is all. Truth be told, they’re perfect for each other.

Ray and me only had two years of marriage under our belt before his wreck, but Grandma and Grandpa had been married fifty years longer than that—although there were times, many times, we thought they wouldn’t make it. But when Grandpa was in the hospital in the weeks before he passed, he told her he loved her at least once a day, which was an improvement from once a year on her birthday. Seemed like he was finally coming around to appreciate what he had. She said she’d been giving him his hormone shots and their sex life had gotten real good again, but that's something I told her I'd prefer not to know details about.

You should see the big torn piece of faded yellow construction paper hanging on the door of their deep freeze. In Grandpa's scribbled marker, it says:

2-14-89 Happy Valentine's Day, Love your husband, Fuzzy. 2-14-90 Ditto.

Men don’t do that type of stuff unless they’re one, guilty, or two, in love. With Fuzzy, it was probably both.

Grandma’s still up there at the coffin while Uncle Butch hands out Kleenexes, and Mom—Mom is looking at her Timex. I didn't expect her to be broken up about it, but she don't have to be so damn obvious. She drove in from Houston this morning and leaves right after the funeral because her job's so all-fire important. That's fine, though, I'm here. Grandma's got lots of good people around her. The church ladies. Ralph and Shirley. And Rue, whose husband just passed a month ago. Rue says Grandma will be OK once she gets over the fact that Fuzzy left her high and dry—just something else she has to forgive him for.

Last Sunday, Grandpa had his stroke around 8:00 p.m. while Fat Faye snoozed in the corner, but it wasn’t her fault. Preacher John went to fetch Grandma, saying that Fuzzy had something he needed to say to her. I guess Fat Faye didn't feel like it was her place to pry it out of him, but we all wish she'd stuck her nosy-nose in their business when she had the chance.

By the time Grandma got all the way to Woodville, it was too late. Two nurses could barely hold him down—he was so agitated about not being able to get his words out. Guess I'd be agitated, too, if I felt the talk freezing up inside of me. Must have been mighty important.

Oh God. I can't watch this. Grandma's up there, kissing Grandpa on his cold, dead lips, and they aren't even Grandpa's lips. Riley made it look like he had a full set of teeth, so now he looks more like President Lyndon B. Johnson than himself. Grandpa had gotten lazy about his teeth since they'd moved up to the country, so most days, his gums would be flapping. If he were barbecuing for the Lions Club or ushering at the church, he'd be sure to have his teeth in. Otherwise, they'd sit in the Stuckey's glass on the dresser. Nothing personal, Ray, but I wouldn't kiss no corpse on the lips for all the money in China—but then stuff like that never did seem to bother Grandma. She was a nurse, after all.

Now the waterworks is happening to me. I swore I wasn't going to bawl, but you watch an old woman kiss her only husband goodbye on his stiff, dead lips—even if he was a no-good lying bastard, and it's got to choke you up. Even Bald Uncle Butch, tough Deputy Sheriff, is putting on his Ray Bans and looking up at the ceiling.

Yesterday, it was Uncle Butch who had to break it to Grandma about the money. He’d worshiped Fuzzy his whole life, kept him up on a pedestal, and then after one lousy trip to the bank, it all came tumbling down. Imagine having to tell your own mother that your own father had cleaned out their entire life savings. No money for the funeral. Or the light bill. Or Grandma’s prescriptions. All gone.

Butch said she shouted at him to get out of her house, and how dare he lie about his father? Then Butch set the bank statements on the table. Guess there’s no arguing with black-and-white, but that's a whole lot of cash for anybody's mattress. Folks around here think he blew it on some woman. Or several. But I don’t buy it. I have to believe he had a plan.

Oh, OK, here comes Riley to tell us the viewing's finished, and we should head over to the church now. Grandma whispers in Grandpa’s dead ear that she'll see him at the boneyard and fumbles in her purse for a handkerchief.

As people file out and Riley closes the casket—I'm watching them close the lid on you, Ray, and I’m thinking about all the things we had left to say. I'm wondering if you ever lied to me, and I'm thinking about the only lie I ever told you, on our wedding night. Remember when you asked me if you were the first man I had ever loved, and I told you yes? Well, that was a lie, Ray. I didn't have the heart to disappoint you, especially not that night when we were so new, but the first man I ever loved was Grandpa, and even though he never actually told me he loved me, you could tell by the way he’d hum me to sleep with his deep voice on nights when I’d feel sad or scared. I wish you had known him longer. I have a feeling y’all’ll be friends up there.

Ever since your funeral, Grandma hasn't missed a chance to remind me that "you can forgive, but you can't forget." I told her about your indiscretions, but even though I made it clear it happened before we tied the knot, she said, “Once a cheater, always a cheater.” I told her we’d been talking, and that I’d forgiven you and that we were at peace. She looked at me like I'd lost my damn mind, and I told her she'd get it someday. Maybe tonight, who knows?

Please, Lord, let her hear him when he comes.

Grandma was forty when she finally had the ear operation. Mom went away to college, and Fuzzy had started looking for someone he could talk to at a lower decibel level. June thought if she could hear, maybe they could talk about things, like baseball, or barbecue, or the gossip at the mill—then maybe he’d love her more.

When they removed the ear bandages, Grandma said it was like the world had been switched back on. The buzz of the lights, the squeak of the doctor’s chair, and then … the deep, gravelly voice of her husband, Fuzzy. The first time she ever heard him speak more than a few sentences was when he told her he was leaving her for that horse-faced bank teller, Gloria. After that, there were plenty of times I bet she wished she couldn’t hear at all.

He never did leave her, though. Until now, of course.

We’re halfway to the church, and the rain is getting biblical. The wipers are squeaking, and Grandma's bitching I'm going too slow, and Mom's yelling from the back seat to let me drive how I please. Whenever Mom gets around Grandma, she talks real loud, I guess a habit from back when she couldn't hear. Grandma secretly turns down her hearing aid whenever Mom visits now—sometimes I've even seen her turn it off. Mom asks if Grandma ever saw their monthly bank statements. She says that Grandpa drove into town every morning to fetch the mail and the papers, and do their banking. She doesn’t even know how to write a check.

I can’t believe he’d leave her with nothing. There has to be another explanation. Please, Lord, let him tell her the truth.

OK, we're pulling into the church.

Everyone's got their umbrellas out, and we're all tiptoeing across the puddles in the tiny gravel parking lot. There's Riley and the hearse. There's Ralph and Shirley. And Debbie, who cleans their house, and it looks like Mule, Grandpa's best friend from the mill, drove up from Beaumont to be a pallbearer. That's nice.

Grandma's introducing me to "the nephews," but before I can say nice to meet y’all, Preacher John takes her arm and ushers her down the aisle to her front-row seat. Mom's up there on one side of her, and Bald Uncle Butch and his wife are on the other. I'm back here with the other grandkids, even though technically, I should be up closer since I was their first grandchild. Not to mention their favorite.

The crowd is quieting down, and Preacher John pushes the button on the cassette player, and "Amazing Grace" comes out of the plastic speaker. The tape warbles, then slows down, then speeds up—and the mourners start giggling. I look over to see Grandma holding her handkerchief to her mouth, and I can feel her heart break. The congregation starts singing along anyway, but I'm making myself read the funeral program, line by line, and I'm trying to think about what the church ladies made for supper. I'm thinking about brisket and baked beans with some of Shirley's cornbread, and as hard as I know how, I'm fighting off thoughts of Ray.

Now Preacher John is winding down his sermon about God and Jesus and the upcoming bake sale, but he still hasn't gotten around to saying much about Grandpa. No mention of Fuzzy Fuesling's good deeds or life achievements. Like at Ray’s funeral, when everyone lined up to tell an amusing type of story about him. Well, no one said anything about Grandpa. Not one damn thing. Don't judge lest ye be judged is what I say.

We're all filing past the coffin now, one by one, and I'm making my eyes look like I'm looking at him, but really, I'm staring over at the peeling plastic Jesus on the pulpit. Now I'm walking back down the aisle, I'm almost to the door, almost free—and then I hear her. I turn, we all turn, and there's Grandma all alone up front, screaming into the coffin, "What was wrong with me?" Screaming right into his face, "What the hell was wrong with me?"

Oh Lord Jesus—she's grabbing his lapels, like she's trying to shake some sense back into him. Now Butch is trying to pull her away, but she’s out of control, and there's no stopping her. I'm in the center aisle, frozen in my espadrilles, but I know it's up to me to do something—I'm the one with experience. So I walk toward the front—my heart's beating, and she's shouting and Butch's screaming at her, and by the time I get up there, she's practically climbing into the coffin. She’s screeching and clawing away at Grandpa, and I'm thinking there's no way in hell I'm ever going to erase the sight of his torn, dead hands as long as I live.

Bald Uncle Butch and fat-ass Preacher John are just standing there while she’s heaving her heart out, and I'm putting my hand on her back and begging her to let Grandpa go. Let him go. I say yelling's not going to do any good and that she's in shock—the same things they told me when Ray passed. But you know what? It's all bullcrap. It won't do her a damn bit of good, 'cuz the pain still grabs onto your bones, and nothing anyone says will make it let go. Because it all sounds like "why." That's all you keep hearing in your head—over and over and over. All you want to know is why.

I'm taking my hands off her now, and I'm backing away. She's fixing his tie, and I'm leaving her be. I'll stand right here and let her say what she needs to say, for as long as she needs to. And as her “whys” continue, no one takes a breath, and all we can do is clear a circle around them … and watch.

It's late, and Rue, Uncle Butch, Grandma, and me are sitting around Grandma's kitchen table, fattening ourselves up on some of Rue's Red Velvet Cake. The church ladies outdid themselves, and we're all stuffed to the gills. My cheeks still sting from the wind at the graveyard, and I can still smell the red carnation I took off the casket just before they lowered him in. I thought I was the only one to take one, but when I walked Mom to her car to say goodbye, I saw another one on her dashboard. She’s not so tough.

Butch is pouring himself a glass of Dickel and fixating on why that Debbie girl, the bleached-blonde house cleaner, was crying so loud at the cemetery. I look over at Grandma, my heart breaking for her, but she's a million miles away.

Rue says she can't wait for Fuzzy to meet up with her husband now that they’re both in heaven. Butch chugs more Dickel and says Grandpa's going to rot in hell. Grandma smiles and nods at them—but I'm the only one who can see that her hearing aid is off.

Once the guests leave, I help Grandma with the dishes, and after that, we sit in the recliners to watch the news. I wait for her to say something, anything, but I know I cannot help her. When the newscast ends, she clicks off the Zenith and looks over at me. Her eyes are so sad. "Am I that hard to talk to?" was all she wanted to know.

"No, Grandma."

Now she's kissing me on top of my head and telling me goodnight.

As I watch her struggle down the long, dark hallway to their bedroom, I'm thinking about love and the liars it makes of us all.

Goodnight Grandma. Sweet dreams.

As I curl back up on the recliner and wait for Ray’s visit, I am surrounded by silence, except for the scrape of the crickets, the tick-tock of the cuckoo clock, and down the hall … the faint sound of someone humming.

*Feature image by Kincaid Jones