Going Off-Road: The Bold Choices of Writer Charles Ray Hamilton

Now a film and TV writer on an unimpeachable career path, Charles Ray Hamilton hadn’t always seen a clear finish line. His journey was interrupted by ‘debilitating’ false starts and ‘dehumanization,’ outweighed by opportunity and the invaluable mentorship others afforded him. All of which the Texas native can credit to a brand of persistence you only see in artists—and the belief that the payoff justifies the journey.

“It really did feel like, ‘We’ve never seen one of your kind before.’”

When he was 13, Charles Hamilton started the eighth grade as a stranger in a strange land. He’d just left the comfortable confines of Killeen, Texas–population 81,000–and moved with his family to Fort Worth, a metropolitan powerhouse with over half a million residents.

Hamilton wasn’t just starting a new school. He was starting a new life.

And what happened next was right out of Jordan Peele’s race-themed horror film Get Out.

On his first day, the white kids in Hamilton’s class grabbed him and started touching him everywhere. One white classmate asked him, disappointed, “Why don’t you talk like 50 Cent?”

Another chimed in, “My mom told me y’all run so fast because y’all have extra muscles in y’all’s legs. Is that true?” Before Hamilton could answer, the 8th grader grabbed his legs to check for himself.

“The 1950s version of racism that I was taught didn’t exist anymore still very much existed and hadn’t gone anywhere,” Hamilton said.

Now 32, living in Los Angeles, Hamilton can look back with clear eyes on the things he endured growing up queer and black in America, and how it’s affected his writing. His journey has a nomadic spark, having garnered an education from places as disparate as a Buddhist-centric university in Boulder, Colorado to the fractious streets of Ferguson, Missouri at a pivotal moment for the Black Lives Matter movement.

He’s also on an impressive upward trajectory in Hollywood. In 2019, he went from writers’ assistant to staff writer on a premium cable show, sold a pilot he co-wrote to Warner Brothers, and (as of January 2020) is one of a select few in the running to adapt a piece of IP for a major studio.

But he’ll never forget that moment in eighth grade. When asked to elaborate on why his white classmates poked and prodded him like they did, he recalls the fact there were two or three other black kids in the class. It’s not like he was the only one.

Then he laughs as he comes to a realization.

“They must’ve thought I was going to bring this kind of gangster thing that these other kids didn’t bring,” he says.

“And then I didn’t, and they were like, ‘That’s not the version of black we put in a request for.’”

“Sweet, calm, peaceful.”

Hamilton can’t hide the fondness he has for his Texas hometown.

“Killeen felt like a Steven Spielberg, suburban idyllic childhood experience,” he says, smiling.

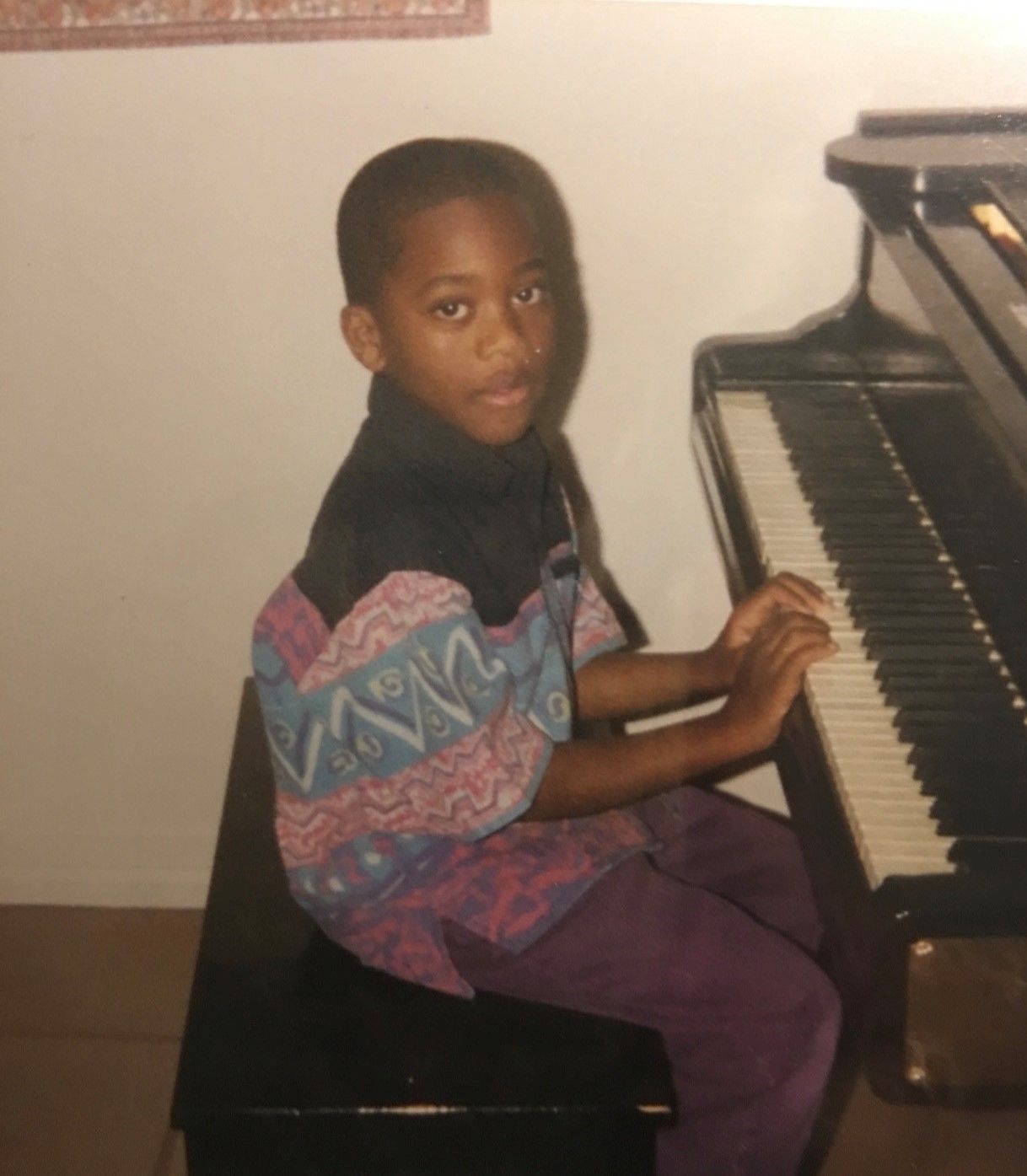

He spent the first 13 years of his life in Killeen, an hour north of Austin. For the majority of his childhood, it was him and his mother, whom he describes as his best friend, and a much-needed antidote to the toxic influences he would encounter early and often.

“A lot of the adults in my life, especially men, were about shoving things down and toughing it out,” Hamilton said.

“[Mom] really fostered the fact I was different. I was an artist. I was a very sensitive kid who always had sort of creative impulses.”

Those impulses were supercharged by an unlikely source. While at his babysitter’s house, Hamilton often watched a VHS tape of the animated classic The Little Mermaid on repeat. A behind-the-scenes segment featuring the late, Oscar-winning lyricist Howard Ashman immediately changed how he perceived movies.

“Seeing there was someone giving a voice to these characters impacted me in a really foundational way. It shifted everything for me, and I was like ‘Oh, that’s me, that’s what I want to do.’”

So his mom began enrolling him in every program imaginable: from acting classes to theatre productions to horseback riding. He spent his summers in a Killeen initiative called College For Kids. In elementary school, he started writing comic books and plays. At first, his friends would perform them; eventually, the plays would be put on by his mom’s church. He wrote three before he was 13.

Then came the move to Fort Worth. Hamilton describes eighth and ninth grade in his new city as “isolating” and absent of the community feeling he’d found in Killeen. The mentors and activities fostering creativity gave way to an atmosphere promoting homogeny.

If you were different, you were ostracized.

And that aforementioned Get Out moment proved to be a harbinger of things to come.

“That was very indicative of what the next years of my life were going to be,” Hamilton said.

“Lots of anger and hate.”

But in the 10th grade, Hamilton had an epiphany. So much of what students were thinking and talking about with their friends was influenced by media. Music, film, television, even the news–all of it fueled topics of conversation at his school. Even the existence of using the word “gay” as a pejorative (“I heard that every day,” he says) seemed to stem from popular culture.

It was 2002. And as a gay teenager in a country still wrestling with the prospect of same-sex marriage–the Supreme Court wouldn’t rule on its legality for another decade–Hamilton had an idea.

“I thought: why don’t I create my own media?”

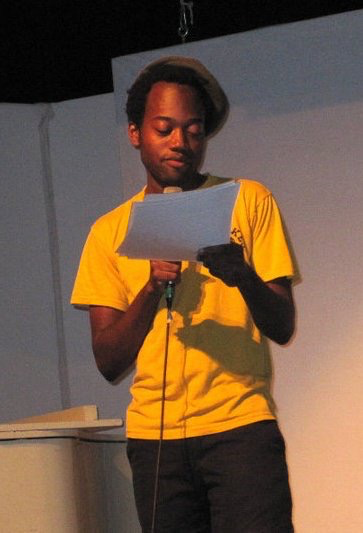

He started Bos TV, setting two milestones: it was his, and his high school’s, first TV show. It was a hybrid of news and parody, and featured skits. He wrote and produced the segments, which were funneled through an intra-network system connected to every television at Boswell High School.

The next year, as a junior, he became editor-in-chief of the school’s newspaper. Now the media he thought had such an impact on the hearts and minds of the students at Boswell High had a new major player: Charles Hamilton.

“I realized that if people who were concerned with truth and compassion took the reins, while also being funny and informative, then that could shift things.”

It didn’t last.

He says a controversy involving an op-ed about gay marriage led to the administration preventing two articles from being published in the school paper. Shortly after, they censored certain aspects of Bos TV. Predicting a loss of control, Hamilton eventually dropped both.

A couple months later, he graduated.

The city of Boulder, as Hamilton says, is home to “Hogwarts for adults.”

In 1974, Tibetan Buddhist Chögyam Trungpa founded Naropa University in Boulder, nestled in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains in northern Colorado. Though it’s nonsectarian, the institution describes itself as Buddhist-inspired. For years, it was the only accredited university of its kind in the United States. Its focus on spirituality and non-traditional educational practices are what eventually drew Hamilton to Naropa some 30 years after it opened.

But he took a wayward path. After an attempt at the traditional post-high school approach–Hamilton attended the University of North Texas for all of one semester before realizing it wasn’t for him–he dropped his classes and moved to Austin, Texas for three years. While working the theater at the University of Texas at Austin and taking online classes, Hamilton began exploring spirituality. He studied everything from Buddhism and Hinduism to metaphysics.

That’s when he came across a book, essentially a translated syllabus from a Naropa University course. The basic concepts spoke to him, and soon after, Hamilton moved to Boulder and enrolled in Naropa’s writing school, the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics.

He makes the above allusion to Harry Potter while laughing. Naropa “has a magical, sort of whimsical element to it.”

“They incorporate spiritual practices and real world experience into the classroom,” Hamilton said, detailing how the institution embraces something called “contemplative education.” Instead of multiple choice tests, for instance, students would write essays on their experiences and what they learned, and how they’d apply it in the real world. Traditional final exams were pushed aside in lieu of rapid fire, peer-to-peer group quizzing sessions.

“It can still be as rigorous as you want it to be, like any school. But it’s about what you learn and how you apply it in a social justice lens, as opposed to regurgitating information you could soon forget,” he said.

And throughout everything, he still had his eye on the entertainment industry.

During the brief semester at the University of North Texas, Hamilton created his first narrative television show, “Cigarettes and Chocolate Milk,” which explored the relationship between two best friends, one gay and one straight. The show focused on how their friendship changes once the gay character comes out to his straight friend. Each episode ran 20-30 minutes, and Hamilton recalled he was so inexperienced that he wrote the scripts in Microsoft Word.

The bigger thing he ties to inexperience: the show’s lack of diversity.

“It was about two white guys. It was a limited point of view for me in my young life, where I thought, that’s what you had to do to get something made or to get people to care,” he said.

That notion is still alive and well, he says, among some in the industry today, more than a decade later.

“Even a few years ago, a black writer in the industry told me, ‘If you want to get staffed, you have to write your first specs about white characters.’ I didn’t take her advice. I stuck to my guns, and I really believe in centering narratives around characters of color, black characters, and people who don’t fit a dominant narrative.”

Once he was settled in Naropa, Hamilton supplemented his contemplative education with screenwriting courses at UC Boulder (“More grounded and normal classes,” he says.). Every spring, he would email his one Hollywood contact–Grant Curtis, a producer of Sam Raimi’s original Spider-Man films–to inquire about an internship. And every spring, Hamilton says he would get the same basic reply: “I’m super busy, I don’t know you, leave me alone.”

Perhaps expectedly, the third time was the charm. Curtis relented.

“He said, ‘If you can be here at this date, at this time for an interview, I’ll think about it,’” Hamilton said.

In 2009, at 21 years old, Charles Ray Hamilton left Colorado and flew to L.A. for the first time in his life.

He recalls that day vividly.

He was nervous. He wore a suit that was too big. His meeting was at Sony in Culver City, and it was the first time he’d ever stepped foot on a studio lot, let alone met with a Hollywood producer. Expectations were admittedly comical: “I imagined a guy in a suit with a cigar and his feet on the desk, barking orders. All the things you see in the movies.”

“Turns out to be this super sweet guy from the Midwest who was very down to earth.”

The meeting proved fruitful. Hamilton made a good impression, and Curtis offered him an internship with Sony on the spot. He moved to Los Angeles for the summer and interned on Spider-Man 4. Though the movie never got made, Hamilton says the education was invaluable. He spent most days at a desk answering phones and reading scripts, but never let that stop him from getting as much as he could from the opportunity.

“I learned one important skill that has taken me through my career, which is going off-road,” he said.

“I was going into different departments, and they’d go to my boss and say, ‘Hey, can I take Charles to the prop house so he can see that?’”

At the end of the summer, Hamilton returned to Boulder for one final year at Naropa with a lot going for him. Back in L.A. was a producer whom he’d impressed during his Sony internship. He’d learned a great deal about script coverage, props, and storyboarding. When he reached out to Curtis right before graduation, he got a good prospect–Curtis was producing a Disney film, and Hamilton could work as a PA on it in Los Angeles.

Then, after graduation, as he was packing up to head west, his phone rang.

“I got a call saying they’d moved the production to Detroit, and they had to hire local people. So ... sorry.”

End of call.

Like that, his lone L.A. gig was gone.

Hollywood is rife with stories of debilitating false starts.

Actors attach themselves to projects just to back out three months later. Networks order pilots that never make it to air. Overcoming obstacles isn’t so much a cliché as it is the industry norm. At times, it can seem like an endless chase.

Hamilton would have to chase a little longer. After that phone call, he spent the next few years splitting residency between Austin and Boulder. He took a job as a pedi-cabber. He did some freelance writing on the side.

Then, something clicked.

“I decided, you know what, fuck it, I’m going to go to L.A. without a job or place to live, get in my car, and go,” he said.

“And my friends were like, you’re insane!”

Nevertheless, they threw him a Hollywood themed going-away party, and someone there offered him a place to stay with their parents in L.A., until he was up and running. He was told they lived in the Pacific Palisades, a place he knew nothing about.

He arrived to something he couldn’t have imagined: a house with a beachfront view in a neighborhood brimming with celebrities. Goldie Hawn. Tom Hanks. Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie.

Three years after his brush with Hollywood employment, he’d stumbled into a hotbed of Hollywood royalty.

“I was just like ... this is incredible,” he said.

Now, he needed a job. He found a gig doing “audience work”–those people who sit in the audience for talk shows, game shows and sitcoms–making $8 an hour. He’d often sneak backstage and chat up guests and employees on the show. How had they gotten their jobs? How’d they break into the industry? What advice did they have for someone like him?

Responses varied.

“Sometimes,” Hamilton said, “It was like ‘Hey, you’re under arrest! Fugitive of the law, go sit back down!’ And sometimes people would tell me, ‘Here’s a number or email address.’”

On one occasion, while doing audience work for "The Late Show with Craig Ferguson," Hamilton talked with a CBS Page about the network’s Page Program. He got the contact information for the person in charge, but was warned that getting into the program was harder than getting into an Ivy League school.

One email and interview later, Hamilton had the job. He worked on "The Price is Right" and numerous ABC sitcoms. The pay was minimum wage, and once he moved into a place in West Hollywood, he was fortunate enough to get help from his father for the first few months’ of rent.

That nomadic spark? It followed Hamilton to California.

The CBS Page Program is, technically, a two-year paid internship. Hamilton left after three months, pursuing a glut of opportunities he sought out nearly every day. He was a set and office PA on "The Bachelorette" for a few weeks. Then, through a series of wayward connections, he hopped on "CSI" for six months as an office PA. Everywhere he went, he made it known he wanted to write, and he eventually landed as a writers PA on a procedural he wishes to keep unnamed.

“Being a writers PA is the hardest job I’ve had,” he said, pausing, then adding:

“I want to be careful here. I’m trying to be precise.”

After a moment, he goes into detail.

“When you take the job, you understand the servile role, and that it’s temporary. But the difficult part is, for me, the dehumanization of that position, especially as a black assistant on a show with rich white writers,” he said.

“There is a certain level of ego and entitlement that can come with being a white Hollywood writer and what you feel you deserve. And when you have a black assistant getting your coffee and lunches, it has a certain optic you can’t escape. That optic can become very real, and it did become real in my experience.”

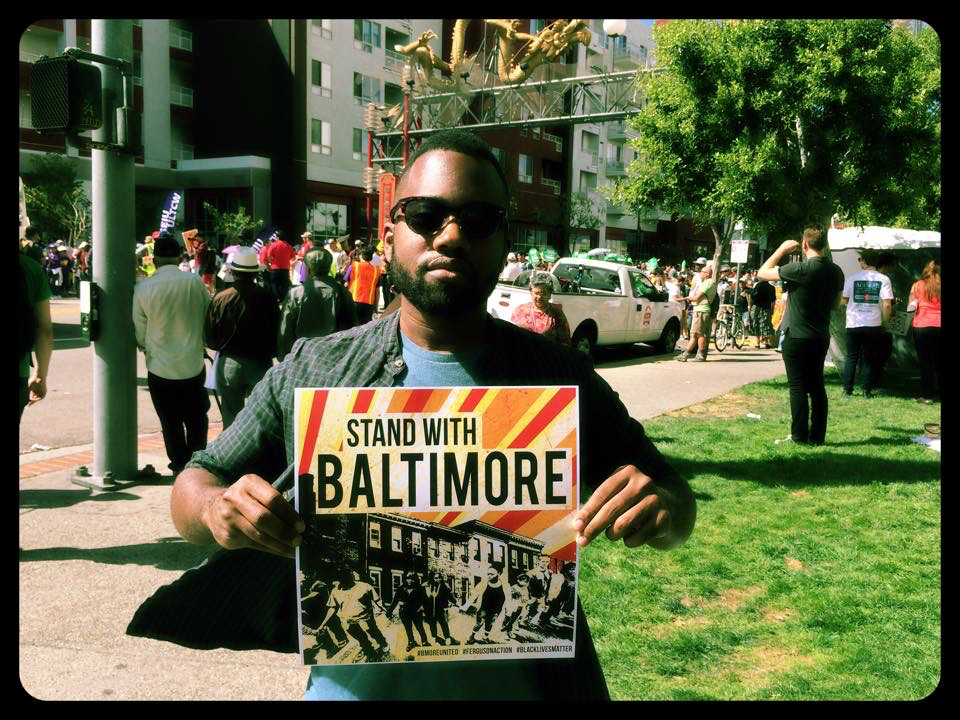

That experience was exacerbated by national events.

This was the summer of 2014. While Hamilton was on the procedural, some 1,800 miles away in Missouri, a white Ferguson Police officer shot and killed Michael Brown, a black 18-year-old. It set off state and nationwide protests, and news of the shooting, along with subsequent marches, became a topic of conversation in the writers room. As the situation escalated and protesters and police exchanged rocks and rubber bullets, Hamilton started getting questions from the white writers in the room.

“A lot of people I worked with took me aside to ask, ‘Why are people there burning down buildings?’” Hamilton recalled.

“My response was, ‘Why are you asking me about buildings and not about the person who actually died? Why is the building your priority?’”

The questions kept coming, and after a while, Hamilton decided he’d had enough.

“That led me to take a break from Hollywood,” he said.

“I wasn’t discouraged from becoming a writer, but I realized I needed to take a different path, get out of game for a minute and become a real person.”

Once out of the game, he got onto a bus headed for Ferguson. There was a national bus ride created as a call to action, and news spread on social media. Black Lives Matter, which began as a Twitter campaign in the aftermath of Trayvon Martin’s death a year prior, exponentially grew in Ferguson. Hamilton arrived amidst a swell of protesters from all over the country. The lack of compassion and empathy he saw in those writers’ questions in L.A. was replaced by what he saw as a morally necessary activism.

His group stayed in Ferguson for five days. When he returned to Los Angeles, he committed to embracing activism as much as he could, to bring everything he’d learned on the streets of Ferguson back with him.

“That was transformative,” he said.

“We began protesting police brutality cases in LA, and from there, I broadened my horizon on activism, about homelessness, poverty. I realized I could use that spark in my writing and become a lot more topical and even incendiary in what I was writing about.”

The energy and excitement in calling attention to these issues was surpassed only by the disappointment Hamilton had in the entertainment community’s response. He says he naively thought those in Hollywood and in writers’ circles would step up, march, and make public comments.

But, he says, those moments never came. It only reinforced the feeling that made him leave that writers’ room in the first place.

“There was a huge disconnect of empathy, between what I was experiencing as a black assistant and that of those I was getting lunch for.”

Hamilton spent the next year in activist circles.

He became friends with Patrisse Cullors, one of the co-founders of Black Lives Matter. He participated in weekly meetings geared toward community and voter outreach, and picketed at events protesting the school-to-prison pipeline.

All the while, his itch to write remained. He wrote a play based on his experiences in Ferguson called It Looked Like a Demon, drawing from the phrase the officer who shot and killed Brown used when describing him in court. Right about the time Hamilton needed a job, a friend messaged him on Facebook to say there was a writers’ PA opening on "Grey’s Anatomy."

An interview later, and he was back in a writers’ room as a PA once more.

Also back? That crippling sense of dehumanization.

“At that point,” Hamilton said, “I became determined not to repeat that dynamic again.”

Being on "Grey’s Anatomy" meant being part of ShondaLand, the powerful production company founded by Shonda Rhimes in 2005. Ray Hamilton became interested in development, and he knew there was an opportunity to learn and grow within ShondaLand. He researched the other shows in development and eventually tracked down Betsey Beers, a prolific producer whose credits included "Scandal" and "Private Practice."

Beers had just returned from Spain, where the show "Still Star-Crossed," a follow-up to Romeo and Juliet, was going to film. She walked past Hamilton’s office heading toward an elevator.

This was his moment. So he hopped in the elevator with her.

“She was going down in the basement where they did post on "Scandal," and of course, she knew I worked on "Grey’s" so I had no business going down there with her,” he said.

“I said, ‘Hey, I know you just came back from Spain, I would love to talk to you about the show.’”

She agreed, and they set a meeting. Hamilton was over the moon, but immediately realized he had to choose one of two strategies: play the long game and try to meet with her a few times, or take this first meeting as an opportunity to voice what he really wanted. He chose the latter, telling her he wanted to be the writers assistant on "Still Star-Crossed."

Cue the bake-off.

While the showrunner and creator both agreed to take Hamilton on, development decided they wanted the candidates to turn in scripts to see who was the better writer. The best writer would get the better assistant position, or perhaps a staff writing job. Industry people refer to this as a “bake-off,” and it can make or break careers.

There was only one problem: Hamilton didn’t have a TV script.

Naturally, he wrote one. In a week.

His script, centered around a police brutality case in Austin, won the bake-off, and got him his first job as a writer’s assistant. He immediately noticed a difference in his duties between his old gigs as a writers PA and this, and how they made him feel about the industry.

They let him pitch. He contributed creatively. It felt like he was an integral part of the process.

“Being a writers assistant, I felt like a person again. The room was so supportive and amazing, and mentored and fostered me in a way that I felt prepared to move forward to next step,” he said.

He spent six months in New York in the writers room for "Star-Crossed" until he was back in L.A.. Searching for the next gig.

It’s an understatement to say finding a job in Hollywood can prove difficult.

But for those trying not to get stuck in a cycle of assistant work, the difficulties are different. More often than not, it boils down to the dilemma of choosing between survival and your personal ambitions. Can you afford to take three months off to make a push for your first staff writing position? Or are you living paycheck to paycheck, and willing–even eager–to accept the first assistant job that comes along?

In any event, Hamilton had trouble finding his next industry paycheck. He knew he didn’t want to fall back to being a writers’ PA, so he set a meeting with his friends at ShondaLand. They’d already read all of his work, and when he arrived, they asked him for something new.

There were two problems.

The first: he didn’t have anything new. So he pitched something off the top of his head.

“I said, I have a feature, and it’s about a fuck boy,” Hamilton said.

He got a laugh. A good sign. He kept going.

“I said okay, he dies, and his ghost is still here, and there is this queer witch who can see him. He learns that, in order to come back, he has to find a way to make it up to his ex from the afterlife.”

They loved it and wanted it by the end of the week.

“I was like totally, I’m just polishing it right now!”

Thus, the second problem: he hadn’t written a word of it.

He set up shop at a coffee place, writing from sunup to sundown, and cranked out a feature in a week. While he never heard back from them, that feature ended up opening impressive doors in the coming months.

Friends and other writers read it and gave him notes. They started sending it out to other writers and industry professionals. It ended up in the hands of Bash Naran, a manager at Writ Large, who offered to represent him. Then, in 2018, it found its way to the showrunners of the Starz drama "Power." They loved his voice and offered him a job as the writers assistant for season 6 of the show.

A few months into his time on "Power," Hamilton decided to put on a table read for his feature. He used all the connections he’d built from his time on different shows and from roaming the halls of ShondaLand to find actors. He invited any–and everyone–he knew.

It was a huge success. Participants included Sheryl Lee Ralph (Dreamgirls, Sister Act 2, Claws), Jerrika Hinton ("Grey's Anatomy," "Hunters"), Darryl Stephens (the lead of the first black gay series, ""Noah’s Arc), and Raamla Mohamed (writing EP on "Scandal").

“At the end of it, I saw the audience really laughed. They were impacted. It made them feel things. People were debating about the ending,” he said.

“It was incredibly life-changing.”

Indeed, it opened several doors. Hamilton met his eventual producing partner, Etienne Maurice, who played the lead at the event. Afterward, producers at the table read approached him about helping turn his script into a film. It also led to him taking that leap all writers hope for: several months after the table read, "Power Book II: Ghost," a spinoff series to "Power," had found its newest staff writer.

The cycle of assistant jobs had finally ended.

May 2019.

Three days after starting his staff writing gig, arguably the highpoint of his career, he got a phone call while on a movie date. It was his writing and producing partner.

They’d just sold a show to Warner Bros.

He can’t say much about the show, which he’d co-written a year prior while an assistant on "Power," but he gives a few details: it’s set in the world of Hollywood, and it has two well-known actresses attached.

A few months after selling that show, another opportunity presented itself. A studio executive who Hamilton was friends with had acquired the rights to a major piece of IP. There was a big director/producer attached. And they needed a writer.

Round one was sending a sample their way. His manager submitted a script Hamilton had written called Greenwood, about Black Wall Street in the 1920s. It got him a meeting with execs (round two), and he gave them some potential directions he felt a feature adaptation could go.

They loved it. He was on to round three. They told him he had two weeks to pitch them everything: all three acts, beat by beat, of the narrative. World-building details, character arcs, plot twists, how themes would be explored. All of it.

“I was doing this while writing and producing two episodes of "Power Book II" and other things that were going on with the comedy we sold to Warner Brothers,” he said.

“At the end of two weeks, I’d gone through this tremendous growth spurt. Both for what I know and feel I can do in terms of being a writer.”

His big pitch to the studio was in mid-November 2019, and he’s since moved on to the final round, which will involve pitching to the director and the president of the company. At the time of this interview (December 2019), the meeting hadn’t been set yet.

That was fine by Hamilton.

“It gives me an opportunity to hone in and make it better with time,” he said.

And no doubt an opportunity to take a breath.

Texas. Naropa. Ferguson. New York.

With every move, Hamilton sought out and embraced unique opportunities. He learned and he grew. Yet with every move, he found his way back to Los Angeles, eager to continue where he had left off.

“When I think back, it makes me happy that a path so unlikely could lead to my exact dream,” he said.

“And at the same time, everybody’s journey to success is unique. I always tell people there’s no one way. So please do it your way. Following your intuition is the path to the truest success: personal fidelity.”

He’s thought often about how far he’s come and how quickly things changed.

After all, he began 2019 as an assistant. He ended it as a staff writer for a big spinoff series, and an executive producer, creator, and writer of his own limited TV series. He’s living–and doing–“the Hollywood thing.”

“It was really like this long build-up to everything happening at once,” he said.

“It feels really good after years of pushing toward something, to see so much of it coming to fruition, and to see people I’ve admired for years recognize my voice and what I have to say.”

Looking toward the future, his goals are broad yet specific. He craves the creative autonomy, in terms of story, casting, music and messaging, that will let him explore pure artistic expression. But he also wants to focus on work that’s healing and liberating. He says he’s turned down big projects for the simple reason that he could see vulnerable communities being harmed in some way.

He also doesn’t want to be constrained to one particular idea or medium.

“I’d always like to be doing something new. A movie, a limited series, a pilot, a play,” he said.

“This is necessarily morbid, but I always think about what I want to reminisce about on my deathbed. I want to remember the bold choices, big loves, and all the risks, whether they paid off or not.”

“But honestly ... they always pay off.”