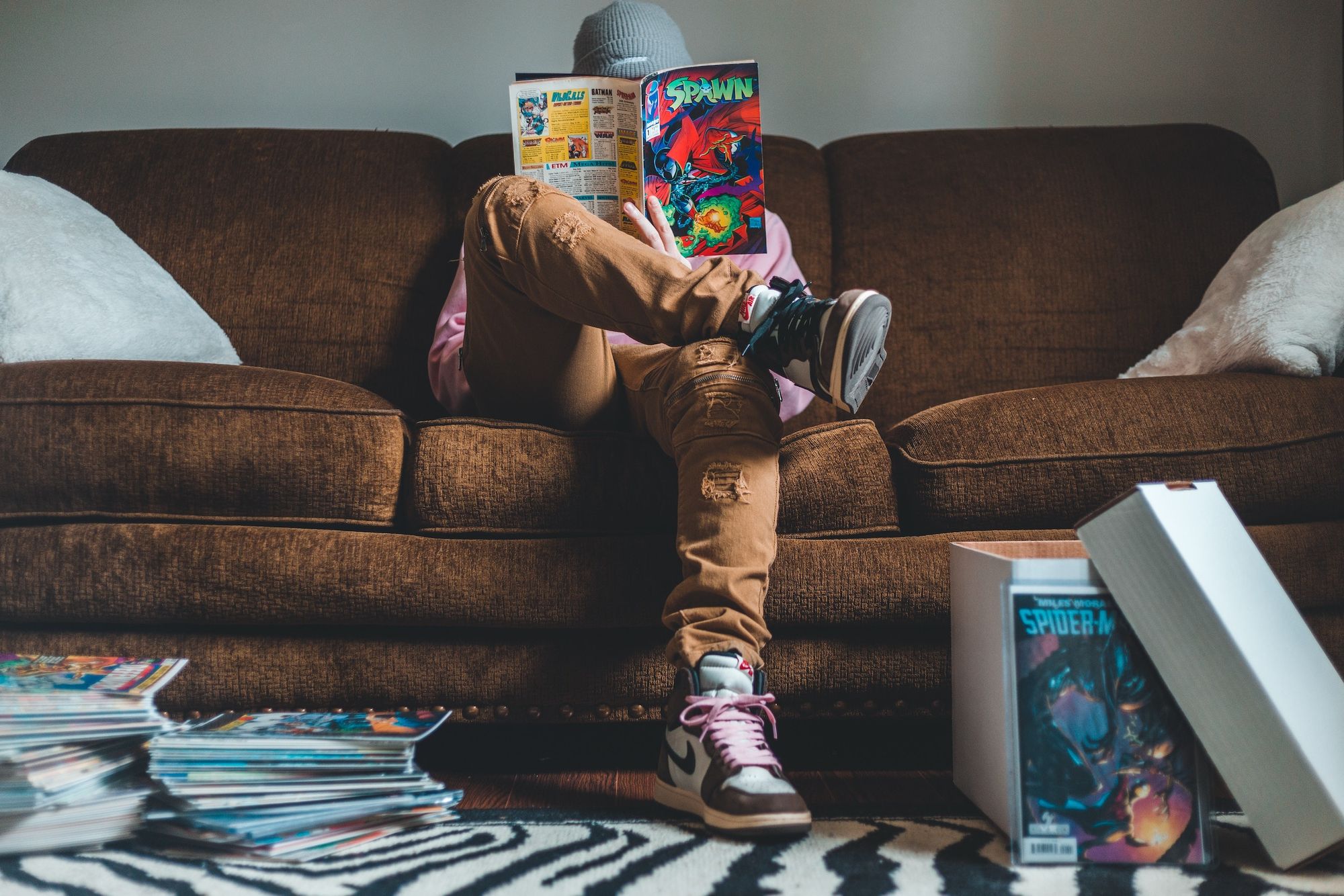

Gutter Talk: Graphic Novel Technique for Screenwriters

When learning the craft of screenwriting, one of the first tenets you encounter is that you should “get into the scene as late as possible and get out as early as possible.”

Simple enough. Great. Got it. But what’s missing here—and what I believe is equally critical to the success of your storytelling—is how you determine where these entry and exit points should be. Fortunately, the sequential art found in the best graphic novels (and in their shorter cousins, comic books) provides some answers.

On a graphic novel page, gutters are the spaces between panels. The “width” or time spent in these gutters depends on what’s going on in the story. In an action sequence, you might see a muzzle flash (BLAM!) in one panel and a wall splattered with blood in the next. Virtually no time is spent in the gutter. In other situations, the time spent in the gutter can vary considerably. It depends on what the writer expects the reader to bring to the story.

What? Are you saying the writer puts the reader to work as a sort of co-storyteller?

Yes. Absolutely. A good writer pushes the reader to draw on their common experiences and fill in as much story as is logically possible while they’re in the gutter. When they reach the point where the reader has no idea what’s coming next, that’s when it’s time to jump out of the gutter and into the next panel.

Not only does using this technique engage the reader, it also frees up pages that the writer can use to tell their story.

What I’m suggesting is that screenwriters (and novelists) think of the spaces between their scenes as gutters and then decide how much story they can realistically expect the viewer to provide while they’re in that gutter. When the viewer can no longer provide the necessary story info, that’s where your next entry point should be.

Let me walk you through the process:

Say you’re working on a screenplay called Indigestion in which one of your co-protagonists, a couple named Kanesha and John, accidentally see a hit going down in a restaurant, and this propels them into the next phase of your story. To get started, let’s say we’re in the couple’s apartment, and John asks Kanesha, “Are you hungry?”

This exit line puts us in the gutter between this scene and the next. Now we’re looking for the latest possible entry point into the next scene. To do this, we’ve first got to decide where the next scene takes place. We do this by asking what or how much we can leave out and safely assume the viewer can provide.

Do we need to see Kanesha and John walking out of their apartment? Nope. Too commonplace. The viewer can provide this.

Do we need to see them getting in their car? Nope. The viewer can provide this, too.

Do we need to see Kanesha and John talking in their car as they drive? Nah. Since they’re an established couple, seeing them isn’t necessary. Let’s save the time (pages) and let the viewer provide this. (If this were an awkward first date, the potential for humorous reveals would most likely make you want to join them for at least part of the ride.)

So far, our choices have been fairly clear-cut, but now they get a bit more difficult.

We’re at the restaurant. You know this is where the next scene takes place. Hooray. A decision’s been made. But your work’s not done. You still have to find that latest point where you can enter the scene.

One option might be to enter the scene in the restaurant’s parking lot with Kanesha and John getting out of their car. (If we haven’t seen the car before, its make, age, and condition could reveal lots about its owners.) As they walk toward the restaurant’s door, everything they encounter could reveal/reinforce their social/economic backgrounds: the building’s exterior (rundown vs. upscale chic), the type of customers going in and out (families vs. celebrity wannabees), the restaurant’s sign (Luigi’s Homestyle vs.—), you get the idea.

As a writer, I can see a viewer being comfortable with the leap from “Are you hungry?” to the restaurant. And I can see the viewer easily providing all the how-they-got-there info based on their similar experience.

But … maybe the better option is to stay in the gutter a bit longer and enter the scene with Kanesha and John already inside the restaurant, at their table, enjoying their meals with wine and smiles. The décor, background ambiance, the owner rushing over and greeting them, the types of customers, etc., all this can be utilized to reveal more about Kanesha and John. And I still think the viewer would be on board with a cut to this entry point. It wouldn’t be much of a stretch to provide the necessary info.

But … but … is this the latest possible entry point? Can we exploit the gutter even more and push the scene’s entry point back even further?

What if we jump from “Are you hungry?” to Kanesha and John walking out of the restaurant after they’ve finished eating? If Kanesha says something like, “It’s still the best veal parm I’ve ever tasted,” then it’s totally clear they’ve eaten. I think most viewers could easily provide everything we’ve left out with info from their everyday experiences. After all, it’s pretty simple. Kanesha and John are hungry. They go to a restaurant. They eat. They leave.

At this point, though—and this is huge—our story stops being an ordinary, commonplace experience. It twists, turns, takes us someplace unexpected, someplace where the viewer has never been before. Which is, after all, the writer’s job. Consequently, the viewer cannot provide any further info. And this is it. We’ve found our latest possible entry point.

With Indigestion, the latest possible entry point has to be Kanesha and John walking out of the restaurant. Why? Because that’s where the unexpected happens. John says, “Oh, damn. I forgot to leave a tip.” He turns and runs back inside. And as he passes an alcove—BLAM! BLAM!—John sees four mobsters open fire on a table of diners. For one long instant a mobster locks eyes with John.

And on that, we jump over the next gutter and right into the next scene where John bursts out of the restaurant’s door. Pushes Kanesha into their car. “We’ve gotta go!”

And before I go:

If there’s a rule here, it’s that the latest possible entry point into a scene is when the viewer can no longer provide the omitted information. Conversely, the earliest possible exit point is when the viewer can start providing omitted information.

Hopefully, this time in the gutter will help your screenwriting.

*Feature photo by Erik Mclean (Pexels)