Looking for New Stakes? Shame on You

Stakes.

They make or break a story. Every story needs to have something at stake; it’s the essence of the classic “hero’s journey.” Are the stakes love? Riches? Life or death?

The risk of death is almost always the most potent of stakes. Hard to top it, really, and that’s why so many stories showcase it as the stakes. We really couldn’t have thrillers or horror movies without it, could we? But because it’s so reliable, death has become the most overused of stakes in storytelling as well. Alfred Hitchcock was once asked why he only made thrillers, and he said that telling a joke is risky. Many will laugh, but just as many may not. Hitchcock argued that if he held a gun on a crowd, every last person in it would have the same reaction: fear. Hitch found it to be simply the easiest way to manipulate an audience.

Yet, there are plenty of other kinds of stakes out there to drive a story, many that haven’t been done to (ahem) death.

One form of stakes that isn’t employed nearly enough is one that in its way is almost as palpable as death. What stakes are those?

Why, I’m referring to the stakes that have driven a multitude of British films and television programs, not to mention a slew of Academy Award-winning Best Pictures like The Bridge on the River Kwai, The Artist, and Birdman.

The stakes I’m referring to? Shame.

Call it embarrassment or humiliation or societal rejection, even guilt, shame is one incredibly powerful emotion. And it can make for fascinating stakes in the human condition when it is at the center of your story.

Shame, as Mr. Webster defines it, is that painful feeling of humiliation or distress caused by the consciousness of wrong or foolish behavior. Additionally, it is a loss of respect or esteem, and even dishonor.

Sounds pretty dramatic, doesn’t it? It is. After all, shame is one awful feeling, an emotion that is universally relatable and quite often as gut-wrenching as that gun Hitchcock referenced. Look at the statistics: 75% of people fear public speaking. 15 million American adults are diagnosed with social anxiety disorder every year. And with the advent of social media permeating our culture, more and more Americans in the internet age fear that a single mistake or embarrassing moment could ruin their lives.

Shame has become so powerful in American culture in our internet age, argues Scott McConnell, executive director of LifeWay Research, that most Americans today fear that a shameful smiting of their reputation is what drives most of their anxiety.

So, why aren’t more stories being written about shame? You don’t have to be Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter or Rodion Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment to experience shame, though those two examples are superb examples of shame driving the plot in classic fiction. Shame can happen in even the smallest of venues, like in a school gymnasium when you’re picked last for the team. Or when a potential date turns down your invitation. Losing out on a promotion can burrow into the pit of your stomach. As can forgetting a significant friend or family member’s birthday.

Shame is, in many ways, like that gun being held on a crowd. Everyone can relate.

And when shame shows up as the stakes in a movie, show, any story really, it triggers our own experiences in wrestling with it. Our blood boils, our hearts pound out of our chest, our mouths dry up, and our faces turn various shades of crimson. Shame instantly raises the drama, and provides stakes that can twist a person in knots.

Think of how The King’s Speech started out with Prince Albert (Colin Firth) having to give an address to a stadium full of people and his wholehearted humiliation when his stuttering handicap prevented him from finishing. French filmmaker Patrice Leconte’s Ridicule was an international hit in 1996, as his droll period piece told the story of how the upper elites in 18th century Versailles, held onto their one-percent stature by how well they could handle acrid insults around the dinner table. If they couldn’t come up with a quick retort to volley back, they could literally find themselves being laughed out of high society. Such was shame in that era.

Shame can be the stakes in high comedy, even on TV. Some of the best comedies rely on shame for its hijinks, like the sitcom Frasier did during its original, 10-year run. The title character (Kelsey Grammer) found himself placed constantly in the most embarrassing of circumstances, whether it was being handcuffed to a hooker, outsmarted by a Jack Russell terrier, or cuckolded by his own brother with ex-wife Lilith. Grammer and the show turned shame into a comedic art, defining the term “slow burn” for a new generation and reminding us that we often laugh hardest at those stakes we can relate to the most.

The small screen has succeeded marvelously as sowing shame for drama, too. For three years, starting in 2004, the teenage-skewed series "Veronica Mars" had shame at the center of its storytelling, often as prevalent as its whodunnit mysteries. In fact, the show’s two main characters wrestled with feelings of shame daily. Veronica (Kristen Bell) struggled as an outsider amongst her entitled classmates in high school, and her father (Enrico Colantoni) was in a constant battle to restore his damaged reputation after losing his job as sheriff in the tiny community. Together, they turned into a private eye duo, trying to solve crimes, as well as fix their own shamed reputations.

And while the stakes of shame always cause mortification, what makes shame fascinating is how it is often wholly determined by what the character cares about. In the 2018 film Eighth Grade, the film’s central character Kayla (Elsie Fisher) stresses about everything that teen girls worry about from their social status to their clique to whether or not they have a ‘cool factor.’ The film plays it for laughs, but because those stakes are so prescient to Kayla, we ache for her even if some of her anxiety earns laughs.

In one particular scene, she is so worried about making the right impression at a pool party and fears her peers will taunt her Kelly-green swimsuit. Then, they don’t even pay a lick of attention to her and her suit. She’s forced on the spot to evaluate what’s worse: the kids laughing at her suit or ignoring her completely. It’s hilarious, and yet in its way, heartbreaking.

In fact, it might be a fun game to think about some of your favorite movies and whether or not one of the central characters is dealing with shame.

Overcoming the shame of being a captured P.O.W. drove Captain Nicholson (Alec Guinness) to foolishly show off his worth by building a bridge for his captors in The Bridge on the River Kwai. Shame drove Cameron (Alan Ruck) in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off to finally mentally break and take the brakes off of his dad’s beloved Ferrari. It’s why Basil Fawlty tripped all over himself every day at work at "Fawlty Towers." It drove Jessica Lange to spend the better part of the third act of Men Don’t Leave hiding under the bed covers. Shame seemed to drive just about every character in "Veep" on HBO. Heck, shame even had a hand in Scarlett O’Hara in shaking her fist and vowing never to go hungry again in Gone with the Wind.

Shame clearly is one very dramatic, palpable emotion. That’s why it makes for such great stakes.

Still, shame is rare enough on the big screen, or small one, so that it will likely never feel like the overdone stakes of life or death. So, next time you sit down to write, consider shaking up the stakes at play and don’t be embarrassed to humiliate your lead.

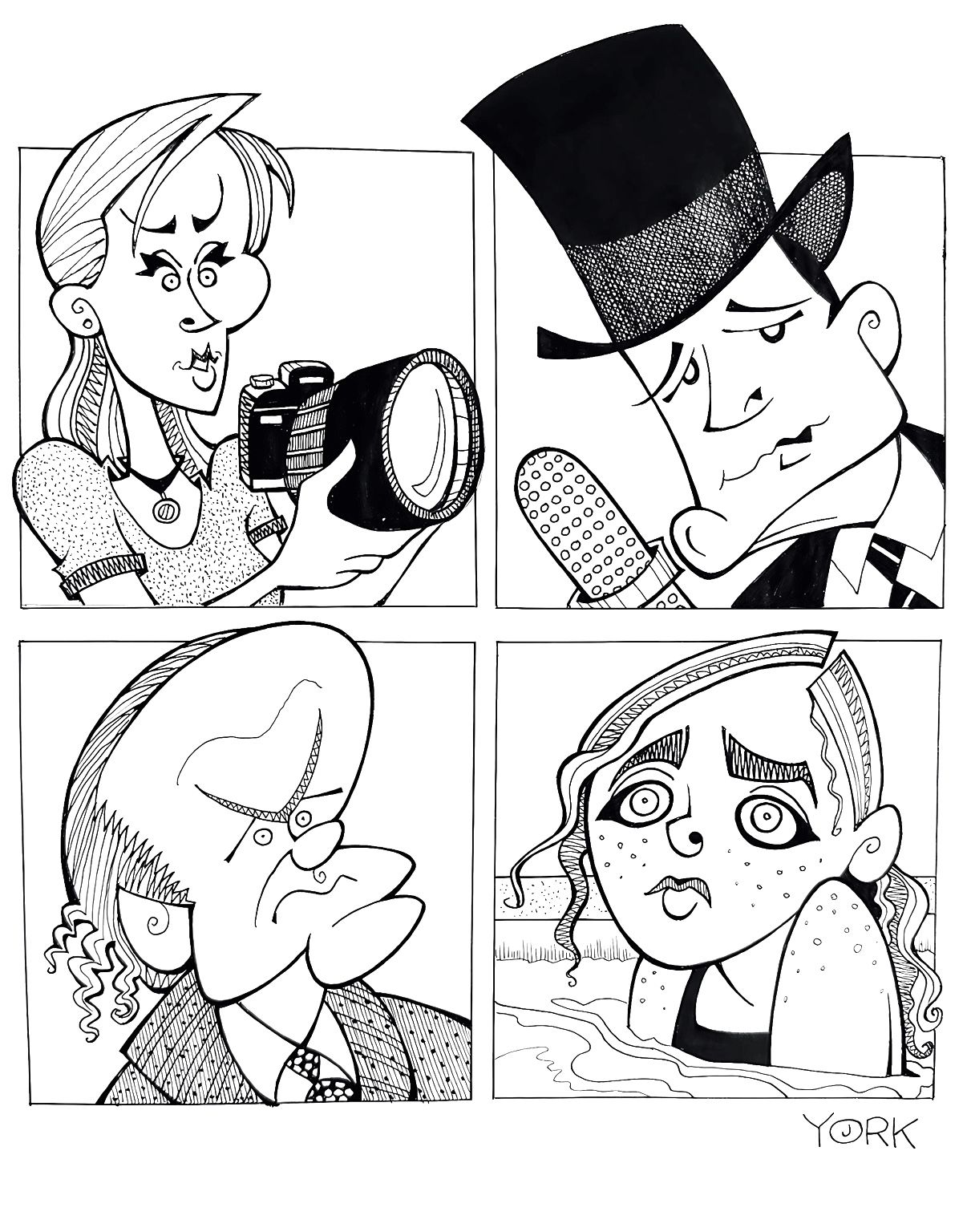

Jeff York’s caricature depicts Kristen Bell, Colin Firth, Kelsey Grammer and Elsie Fisher.