The Life, Death, and Rebirth of Film Projection

A Primer on Film versus Digital

This past summer, I had the pleasure of visiting a modern projection room at a multiplex. (One can’t exactly call it a projection ‘booth’ when it runs the length of a football field; if a football field was indoors, had sharp corners, and had oversized movie props in seemingly every available corner.)

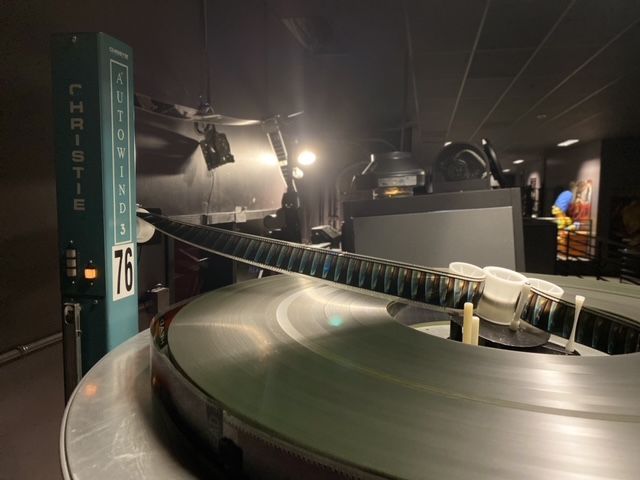

Walking past the array of DCPs (Digital Cinema Projectors), showing generic summer blockbusters to moviegoers devouring their popcorn while surreptitiously glancing at their iPhones, I wasn't sure I was in the right place. Then I turned the corner and saw this enormous three-level rotating platter, connected to an even larger 70mm film projector. A massive reel of the three-hour Oppenheimer print unspooled from top level of the platter to the projector and spooled back to the bottom platter after being projected onto the screen. The film print itself apparently weighs close to 400 pounds and would be eleven miles long if stretched out—across the city of Los Angeles, perhaps. (Note: this was the standard 70mm print, not the IMAX version that Nolan preferred and was released on only 19 screens across the United States.)

I had already seen the IMAX Laser Digital version, and I was astounded by how richly textured the 70mm film print looked—even through the small port where the projector beamed the light into the packed theatre. When I ventured down to the sit in one of the few unoccupied seats later, I was completely hypnotized by the celluloid on the screen. In fact, I was saddened that I had allowed my son to convince me to see it in IMAX. (To be fair, we both had wanted to see Oppenheimer in IMAX 70mm, as Nolan recommended in seemingly every damn interview he did, but the screenings were sold out for weeks.)

After experiencing the beauty of a pristine film print, I thought that it was time to do a deep dive in the differences between film and digital.

Was it purely aesthetic? Were we merely watching a big screen TV masquerading as theatre, as filmmaker Quentin Tarantino complains? (One of the myriad reasons QT only shows films prints at his theatre, The New Beverly Cinema, in Los Angeles.)

It was time to ask the experts and learn the answers.

Beyond the literal beauty of screening 24 frames a second of celluloid film through a beam of light versus a hard drive with binary data extrapolating the image to the screen (a sentence that almost made me fall asleep while typing it), I wanted to speak with experienced projectionists about the differences between film and digital.

I spoke to four knowledgeable projectionists, as well as a member of the next generation.

(In other words, fear not, dear reader: the unique skillset and art form will continue into the foreseeable future.)

The players:

Jess Daily: MFA UCLA, Member IA 1996. UPTE (UCLA) 1983, Former Chief Projectionist at the UCLA James Bridges Theatre.

Marc Shevick: Fairleigh Dickinson University. IATSE member since 1964. Worked at Paramount Pictures as studio projectionist and then at MovieLab.

Brad Morris: San Francisco State. He currently works for an L.A.-based non-profit that screens films on a regular basis for the public. He also continues to screen films for private individuals and is a proud member of IATSE Local 695.

Tim Kennelly: Columbia University. The Trumbull Company, Pixar Animation Studios, Academy Museum, Paramount Studios, Television Academy, & much more.

Clara Baker: Archivist at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences and protege of Jess Daily.

Scott Sanford Tobis: Can you put into your own words the difference between projecting film and the digital medium?

Jess Daily: Film is more immersive. Digital is hard, crisp like TV. I love handling film. To see it and touch it. It’s real and beautiful.

Marc Shevick: Film was more fun to run, where digital is just one big bore. When I remember my projectionist days, I only remember projecting film.

Tim Kennelly: It’s different technology to achieve the same ultimate end—to tell visual and aural stories; suspend the audience’s disbelief, and transport them into a space beyond their everyday life. I’m not an either/or person. They both have their own strong points.

Film is a fragile and mortal medium, which requires human care to maintain its quality, and there’s a lot to be said for having a medium be tactile and mortal—one really has to use a lot of care in handling & presenting. On the other hand, digital will look as perfect on the millionth showing as on the first—there’s no physical degradation from repeat showings.

Brad Morris: The major difference is that you are less involved with digital projection once it hits the screen.

With film, your actions are needed to make a moving piece of art be as its creators intended for the length of the movie.

There are small adjustments to be made throughout the film that affect what the audience sees and can shape their experience. With digital, the DCP is going to do what it's going to do, and your ability to change that is minimal. Something unique that film offers is that you're handling and taking care of a physical element, sometimes with fascinating provenance. It may be the best or only known copy of something you've been trusted to handle. Prints struck from the original camera negative, answer prints, studio archive copies, a director or filmmakers personal copy of a print, ones that screened at the premiere. The lab leaders also can tell a fascinating story. Was this recut? When was the reel printed? Was there a working or changed title? Which version is this? You don't get that from DCP's. A file is a file.

Scott: Clara Baker had a much more emotional reaction to the question. Not surprising, as the old adage goes: no one is so self-righteous as the newly converted. (In this particular case, this is a positive attribute.)

Clara Baker: Film is so much more alive and personal than digital projection. Knowing that someone took the time to inspect the print, threaded the projector with care, and is monitoring the entire show connects film projection to a live theater experience. With digital, everything happens offsite! It’s so cold and impersonal. Filmgoing is a communal experience people have enjoyed for over a century, and there’s nothing special about it. If there are problems in your screening, they don’t get fixed unless you leave the theater and report it. Why wouldn’t people stay home and watch in an environment they can control themselves?

With film projection, you know something special is happening. You’ve arrived in a magical place where you can suspend your worries, because someone is waiting to dim the lights, open the curtain, and start the show.

Favorite moments from the front lines of the projection world:

Jess: When Ali McGraw came to the booth and introduced herself at Robert Evan’s house. I was ready to start the show, but there was no one home, and she didn’t know anything about a screening.

Marc: The first time I was sent by the union to work in a theatre by myself without anyone overseeing it. Yes, I was nervous, but it was everything I had hoped it would be.

Brad: While doing a screening of a huge film for the studio executives who hadn't been allowed to see the film. Big name directors can do that. The run-through went fine, but the film system started acting up as the audience was loading in and wasn't going to work. We had a digital backup, but because there was such an emphasis on this being shot on film, and the costs involved, it didn't look good for the filmmaker to not screen it on film.

Minutes before we were scheduled to start the show, the technician fixed the issue (we hoped), and we had full functionality back again. I called down to the Post Production Producer to tell him we could still do film, if he wanted to. He told me to hold on while he asked the director. I heard him ask, and then heard the director say, "Well, what does Brad think we should do?" I told him I was confident and that we should go with the film. We did, and thankfully had no issues during the screening. I was sweating that one the entire time!

Tim: Running Baraka in 70mm at the Dubai Film Fest in 2004, on a 75-foot wide, outdoor screen. One of my favorite movies, and since it’s about Man’s relation to the divine, it includes rituals of the world’s major religions, all as equals—we are just humans trying to get in touch with our higher spirit. Images of Jews praying at the Wailing Wall, in the same sequence as worshippers at the Grand Mosque of Mecca, circling the Kaaba ... this was a historic moment in the UAE, as in the Arab world, you rarely ever see images of Jews and the Wailing Wall in the media, and here we were showing that (and all the other profound imagery) in glorious 70mm with that majestic soundtrack.

Another moment: installing a projector in David Lynch’s home in 1998. It was the same house where he filmed Lost Highway. After we finished installing the projector, at his request, we tested it with his personal print of Eraserhead. I’m a huge Lynch fan, and was tingling all over, to be standing a few feet from the creator of this film as we unspooled its haunting images and sounds.

Scott: Tim had many wonderful favorite moments, so I’ll indulge him a third ...

Tim: At the Taos Talking Picture Festival 1996, I ran a terrific film called Caught, starring Edward James Olmos. Before the start, the director, Robert M. Young, requested a projectionist to come downstairs for a word. Several projectionists were working, but I had the walkie, so I went down. He shook my hand and said something like, “I just want you to know that after all the time, money, and effort spent on this film, you are now a part of this continuum, a vital part of this project, because all of our work is in your hands, to present it well. So, I wanted to welcome you to the ‘family’ of hard workers that made this movie—you are now a vital part of it.”

It was an astoundingly gracious thing to say. I walked back to the booth, swelling with pride, and boy did my fellow projectionists and I present that show with extra conscientiousness and care. I’ve shown movies to a lot of huge directors—Nolan, Cameron, Spielberg, Tarantino, Del Toro, all the Pixar directors, but that chat with Young was one of the most memorable of my life.

Clara: Standing in the booth during a 70mm screening of Oppenheimer, my mentor called attention to a line in the credits that said, “Shot and cut on film.” The image of him standing there next to this massive projector with the screen visible behind him will forever be in my memory, because in that moment I felt connected to all the people who come together to make a film happen, both now and in the past. I am fortunate to work with production art material, so I already have a deep love and respect for the countless, often unnamed, artists who contribute to film productions.

Film projection is an extension of that—an unseen person in the booth working so that audiences will have a special experience. Films deserve to be treated like the pieces of art they are, and film inspection, projection, and preservation are in service of that goal.

Humorous stories:

Jess: Barbara Streisand came to the booth at (legendary TV producer) Norman Lear’s house. I was also working occasionally at her house. She said, “Jess, where am I?” I looked confused. She explained that she needs to go home and doesn’t know the address. (This was before cell phones.)

Tim: At Sundance in 2002, I ran (the) premiere of Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later. I was shutting down the booth and could see out the port window that the house manager was walking the aisles of the empty theater. I timed it just right, so that when she came out into the dark lobby, I burst out of the projection booth screeching and wild-eyed, running at her like an infected zombie. She nearly died from fright, then from laughing.

Marc: While still being trained, we were running a re-release of Psycho. The next film coming in (was) Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machine, which turned out to be a mag/opt print. Since the theatre had originally been set up to run mag prints, I asked the man training me if the mag system still worked. He responded, "Let’s try it," and turned the system on (while still running Psycho). Since the system had not been turned on in years, and the system was an all-tube system, (it) caused a large cracking sound to shoot through the theatre—just at the point where the dead mother sitting in the basement turned around, causing people in the audience the jump. Later, when I was leaving the theatre, I heard people saying they didn’t remember that happening the last time they saw the movie. I just smiled.

Brad: One that stands out was having a studio representative tell me they had a gun in their car, and that they'd shoot me if the studio logo opened on a partially closed curtain. Maybe humorous isn't the right word ...

There are clearly lots of opinions out there on the benefits of film versus digital. Not too dissimilar from the vinyl vs. digital debate from the not-too-distant past. Digital has some definite benefits. As Tim told me, it “will look as perfect on the millionth showing as on the first—there’s no physical degradation from repeat showings.”

The only difference is that casual film lovers can’t purchase a film projector the way someone might buy a turntable, amp, and receiver for their home. The art of film projection requires not just the technology, but the space to house a theatre that envelops the audience with picture and sound.

Tim said something else that was quite interesting: “A little-mentioned aspect is that digital cinema is a constant light source. Whereas film relies on flickering of the shutter, so half of the time you’re “watching a movie” you’re also watching darkness. There’s a floor in our optic nerve that sees these intermittent images as continuous images … so that’s a neat trick that our brain does. Some have suggested—I think Roger Ebert was one—that the phenomenon of flickering light induces more of a state of “reverie” in the human mind, closer to the beta-waves the brain produces in dream states. We don’t get this with constant-light digital sources.”

The good news is that film projection is not dead. Oppenheimer was perhaps the gateway drug that moviegoing audiences needed. Apple Films is releasing a 70mm print of Ridley Scott’s Napoleon. It certainly won’t be the last movie projected on film. Tarantino’s (ostensibly final) film, The Movie Critic, will be shot on film and almost certainly be projected on film in certain locations. Recent movies like Kenneth Branagh’s Death of the Nile had multiple film screenings and even Michael Mann, a filmmaker who has fully embraced digital filmmaking, recently screened his own 70mm (blowup) print of his seminal work, Manhunter, for the Beyond Fest in Los Angeles. And in November, the the newly restored Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood will reopen with great fanfare with their Ultra Cinematheque 70 Fest 2023. (As they own their own prints of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Lawrence of Arabia and other classics, it’s a must-see event for cinema lovers.)

Even better news is that there’s a new breed of projectionists on the horizon. Clara is just one of many, eager to learn the art of film projection. (I have to imagine after reading the article to this point, the reader would have to agree of the value of the art form.)

As I left the projection area at the multiplex where I had watched Oppenheimer in glorious 70mm, I passed by the digital machines spewing out binary codes in the form of images on the myriad screens. My cynical brain was about to kick in before I spotted the images from a beautiful, low-budget, independent film projected onto a screen. Perhaps a film that could not have been shot, nor released, in the era of celluloid film.

As it is said, film is the rare art form that the artist cannot afford the canvas on which to paint. Digital filmmaking has changed that.

The thing is both types of film can co-exist. There is no reason for film projection to disappear, and many reasons for it to remain—as it’s vibrant art form. After all, artists didn’t stop painting when photography was invented. Those two forms co-exist. My belief is that film projection will continue to exist well into the 21st Century. There are benefits to both art forms and, as the next generation of film projectionists (in the form of Clara) told me: “Art demands to be seen, and I love to present it to people in the best way possible.”

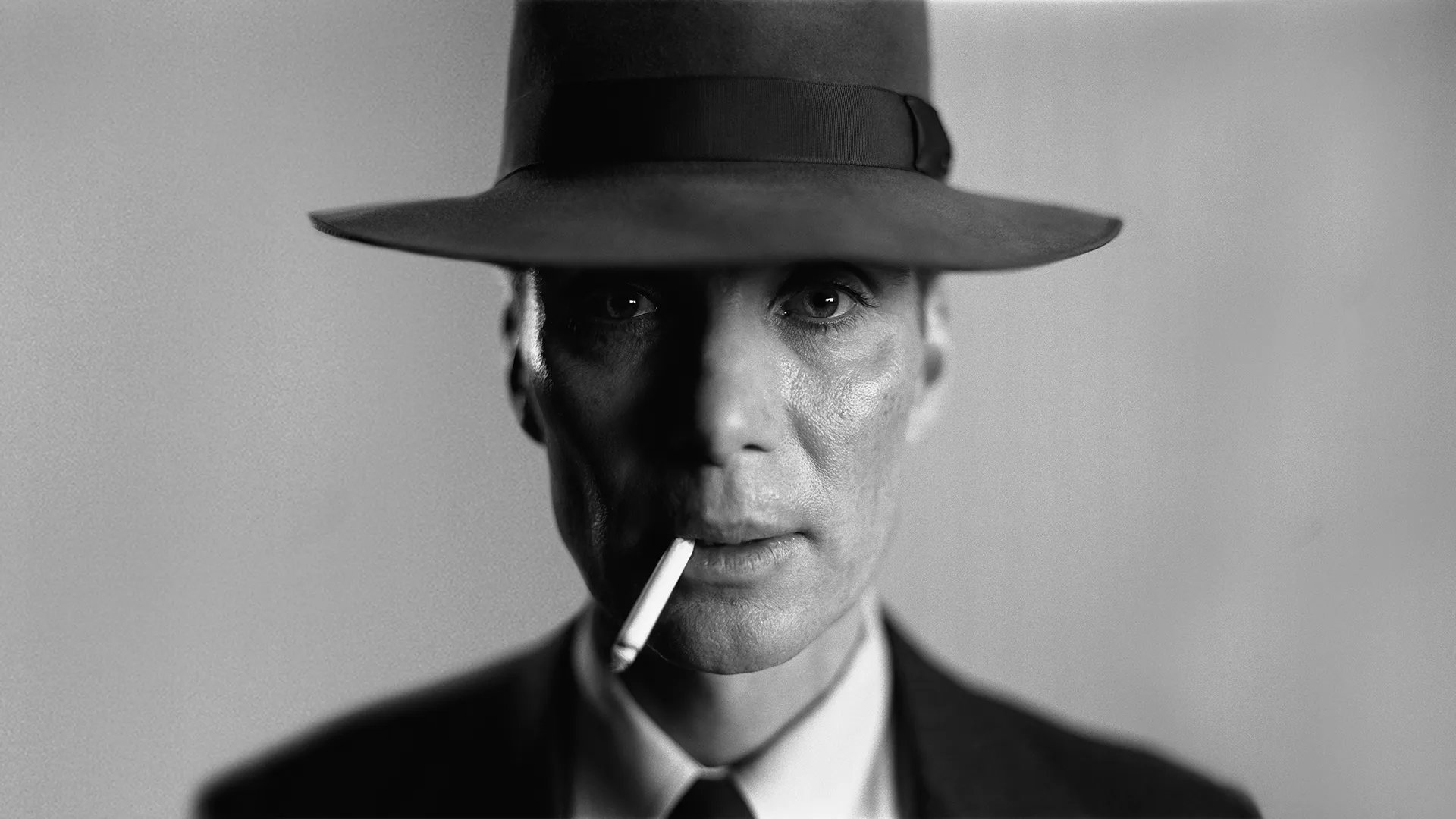

*Feature photo, Oppenheimer (Universal Pictures)