The Limited Series Isn't Just Having a Moment

The limited series genre is having a moment. A ginormous one. One that goes well beyond the binge.

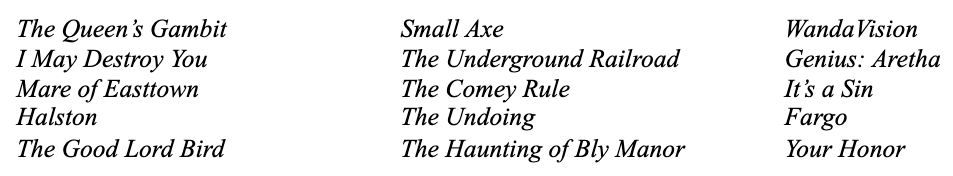

Just how big a deal are limited series these days? Well, imagine you’re an Emmy voter and these are the choices you must whittle down to five or six nominees as the year’s crème de la crème in the Limited Series category:

"The Queen’s Gambit" may be the frontrunner, and I think it should be, but in any other year, "Small Axe," "I May Destroy You," "Mare of Easttown," or maybe even "WandaVision" would likely win in a walk. This year, they may all have to settle for runner-up, to say nothing of the half dozen other notable limited series that may not even make the final cut.

During the first decade of this century, television drama enjoyed a renewed golden age with series like "The Sopranos," "Mad Men," "The West Wing," "Breaking Bad," "Lost," "The Wire," and "Dexter" … just to name seven. Yet, as we’re into the century’s third decade, the limited series is now attracting most of the heat. Not since the 70s and 80s have they been so heralded and popular.

For those old enough to remember, that period was the last time the miniseries, as they were called then, made such a splash. The likes of "Rich Man, Poor Man," "Roots," "The Moneychangers," "Captains & Kings," "East of Eden," "Centennial," "Shogun," and "The Thorn Birds" made appointment television for record-breaking audiences when they ran.

Perhaps you noticed those titles listed from 40 years ago were all adaptations of books. Indeed, one of the reasons limited series flourished then and now is that they can tell longer stories, like those adapted from novels, in a format ideally suited to dramatize more expansive works. Episodes of limited series like "Big Little Lies" and "Normal People" spooled out like chapters, perfectly modulated for their running times.

Limited series included the anthology variety as well with the likes of "American Horror Story" and "Fargo" running multiple seasons with a general theme, horror, and noir in their instances, but with different settings and characters. If it’s not a regular series, or a TV movie, it most likely qualifies by today's standards as a limited series, and audiences are drawn to the catch-all of variety such a format can house.

That range of storytelling has also become a boon for those above and below the line in the industry. Film actors can work on the small screen without making a five-year commitment to a regular series, and writers of all stripes can cross back and forth without getting tied up for years either. Additionally, television production values are now wholly equal to those in movies. In fact, the limited series really must be considered long-form filmmaking, a brilliant hybrid of the best of the big and small screens.

Indeed, for years now, many limited series make up the best work coming out of Hollywood. A-list stars go back and forth between TV all the time these days, and nobody bats an eyelid when the likes of Reese Witherspoon, Nicole Kidman, Hugh Grant, Al Pacino, or Kate Winslet take on television roles repeatedly. Often, limited series scripts are more appealing to them than various film scripts they’re being offered, so they go where the best work is done. That’s most certainly true with women’s roles.

And the writing in limited series is, more often than not, wholly richer, deeper, and ultimately more satisfying than two-hour theatrical releases for actors and audiences alike. Having more time to tell a story is part of it, of course, but how many Best Picture Oscar winners had stories that truly surprised and became water-cooler conversation in the last decade? Outside of Parasite, few winners have truly startled and become hot topics the way limited series such as "The People vs. O.J. Simpson," "Watchmen," or "The Queen’s Gambit" became.

Additionally, a limited series that appears on an unrestricted platform like Netflix or HBO can show as much nudity, violence, and profanity as any R-rated theater fare. Limited series are also more unpredictable than either films or regular television. In a regular TV series, a recurring character isn’t going to be killed off. The same is true within a movie franchise. In a limited series, however, such rules need not apply.

Anything goes, and often does.

All of this is especially exciting for the screenwriter. Gone are the rigid rules governing a two-hour movie and a weekly series of 30 minutes or an hour. And the limited series allows writers to zig more than they can elsewhere. In movies and TV these days, the familiar tends to bore audiences, or lets them get ahead of the story. They know what’s coming based upon hours of watching such constricted stories. But the limited series has none of those time constraints.

Instead, they are unpredictable because their form isn’t predetermined.

Which brings me back to "The Queen’s Gambit" ...

Some of its success can be attributed to a captive audience stuck at home during the pandemic looking for fresh content to watch, but much is due to its utter brilliance at every level. Creator Scott Frank adapted the clever 1983 novel by Walter Tevis and turned the piece into not only a vivid character study but a suspenseful thriller. That was no mean feat given that the lead character Beth Harmon (Anya Taylor-Joy) was an introverted young woman in the 1960s who becomes a chess champion.

That premise sounds sleepy. It never is.

Frank took his time with the story, doling it out carefully and precisely. The series built up Beth’s complexities bit by bit, never giving away too much too soon. She was also surrounded by fascinating supporting characters, played by an expert cast.

Most importantly, chess was treated with great care, executed more like tense boxing matches than a sit-down board game. "The Queen’s Gambit" was wholly cinematic with its full-orchestral score, production values, and costumes. (Beth’s clothing was almost always color-blocked, like a chess board.) Why, her hairstyling even created a stir, becoming physical metaphors for chess pieces. As a powerless child, Beth wore a pageboy cut that made her look like a pawn. By the end, the triumphant lead was adorned like the all-powerful Queen in winter white.

Beth’s story twisted and turned, never going quite where you expected it to either, and the climactic final match was somewhat anticlimactic in that her true victory occurred earlier when she learned to accept herself and her friends. A two-hour movie might have made such an arc too quick or blunt, and a long-running network TV series would probably never have allowed her to be so flawed, so drugged out, and so sexualized. In the limited series format, however, "The Queen’s Gambit" found a perfect fit.

Indeed, the limited series offers storytellers a variety of possibilities that seem utterly limitless.

*Feature image by Jeff York