The Orgasm Box: A New Universal Model for Storytelling

If you’ve studied enough, you’ve probably come to realize that story structure is pretty basic. Every theory more or less recycles the same formula under different headings. We have the character wound (aka the internal need), the dramatic question (aka the external goal), the inciting incident-catalyst-call to adventure, the midpoint-mirror moment-reversal, the all is lost-dark night of the soul-break into III, and nobody ever knows what to do with Act II.

All this homogeny makes sense. Most stories follow the same three-act structure that started trending with Aristotle way back in toga times. Self-appointed screenwriting gurus have figured out that if they can find a way to cram all these ideas into a simple graphic and give it a catchy title, writers will eat it up. We can’t be trusted to make good decisions when we’re scrolling Amazon in a caffeine crash at 2 a.m., desperate to find a fresh new way of resolving the same old structural issues.

“If there were only a cute geometric roadmap that could get me through this block,” we cry, “I’ll never sin again.”

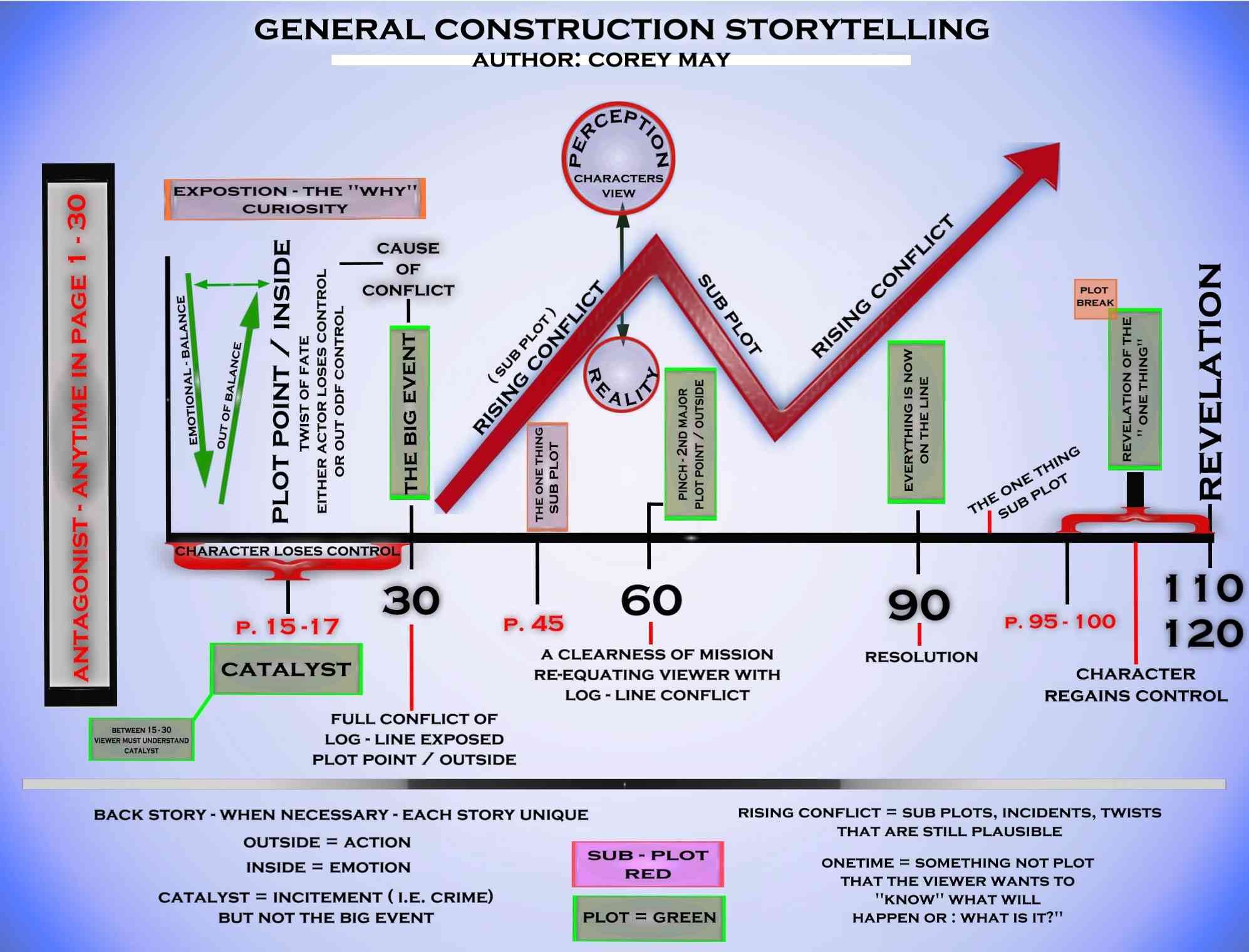

Our willingness to bargain with the devil has given birth to some pretty heinous diagrams. We have the triangles, the circles, the diamonds …

… the quarterly earnings charts …

… the, uh, circus tents? ...

… the whatever-the-hell-this-is …

… and of course this absolute abomination.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t feel any clearer after looking at those. I do, however, have a wicked case of trypophobia.

Writers, we need to break from tradition and free ourselves from the trap. I propose that it’s time for a new model; a model, not focused on what happens, but why; a model that truly captures the essence of every story; a model with guts and heart and sex appeal and bitchin’ VFX!

But how?

To start, all of the existing models focus on the wrong thing. They are about what happens (plot), but they are divorced from who they happen to (character). The same formula will merit different results depending on the qualities of the character experiencing them.

To see things differently, we need to look at who the story is about and why we tell stories in the first place.

Every single story is about some part of the human condition. Even stories about dinosaurs or space robots are about the people they represent or the people who encounter them.

The human condition is a blanket term that encompasses all of the aspects of human existence: birth, knowledge, complex emotion, ambition, conflict, death, etc. (Or, the things that raise us over other animals, if you want to be egotistical about it.)

Of course other animals experience some of these events, but the crux is how we react to and cope with them. Humans are supposedly more aware of our mortality, which makes us really, really freaking nervous. We want to have purpose beyond popping out babies and dying, which creates all sorts of big questions—the existential dilemmas that simultaneously form and plague us.

Naturally, it’s an endlessly fascinating topic for storytellers.

I have an untested theory that this fascination is what takes us off the structured path and leads us into the narrative weeds. When our characters start to become real to us, they make choices that we did not plan for them when they were only sketches. We start saying things like “that character wouldn’t do that here,” even when our handy plot diagram says they must.

It gets difficult to play God once your characters develop free will.

So, if all stories are about trying to understand what makes people tick, and we want to figure out how to voice that in simple terms, then it’s probably time to take a field trip to the Magical Realm of Psychology, baby! If there’s one group of bigger neurotic weirdos with antisocial personalities than writers, it’s psychologists. While we write to understand the human condition, those guys have devoted their lives to trying to fix it, the poor suckers.

A fun game I like to play when I’m blocked is to imagine what different psychologists would say about the topic at hand, according to their major theories.

For example:

Me: Should my main character jump off this bridge?

May (humanistic): He’s gotta’ do it, man. If he doesn’t face his fears now, he’s screwed.

Piaget (cognitive): Some idiots never learn.

Perls (gestalt): He won’t jump because deep down he knows it will hurt her, she’ll seek comfort in the arms of his best friend, and in the end, he’s only hurting himself.

Jung (psychoanalytical): It’s so against character. You can’t make a man act against his own nature.

Pavlov (behaviorism): :giggles:

OK, we might be stretching the definition of fun there. Whatever. The point is that being human is not just about going through the motions of doing tasks with increasingly higher stakes. You can’t find the meaning of life through purely scientific processes, and you can’t lead your character to the right solution by leaning on a mechanical story model.

Psychologist Wilhelm Reich laid it out pretty clearly:

The question, "What is Life?" lay behind everything I learned. ... It became clear that the mechanistic concept of life, which dominated our study of medicine at the time, was unsatisfactory ... There was no denying the principle of creative power governing life; only it was not satisfactory as long as it was not tangible, as long as it could not be described or practically handled. For, rightly, this was considered the supreme goal of natural science. [pp. 54–55. From Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich, 1994.]

So, to make our model truly original and worth the hassle of trademark registration, it has to sprout from the human search for purpose. This can be through the lenses of different schools of thought, as demonstrated above. It can be through different characters representing some element of the human condition (anxiety, death, hope, and knowledge walk into a bar). It can be a character exploring variations on the theme on a metaphysical level—what does it mean to be a person in relationships, in society, in this universe? What it will not include is an obligatory third act plot twist.

Wilhelm Reich was quite a character himself. (PLOT TWIST! This entire introduction was an elaborate ruse to create a vehicle to talk about this guy. Pointless deception: a purely human characteristic.) Reich was an antifascist, he studied under Freud, so you know he likes to party, and he is credited with coining the term “sexual revolution.” Today, he would be the most popular adjunct professor in your college psych department. His research focused on how the physical body manifests symptoms of mental illness. He thought you could discern a person’s diagnosis by observing their movements.

Full transparency: he was also a little bit nuts. He thought orgasms could cure cancer and a host of other illnesses. He called himself an Orgasm Collector and invented “sex boxes” that were basically just metal coffins where people would do their personal sinning. They were wildly popular among actors. He also made a “cloudbuster,” which was a water cannon that he shot into the air to break up excessive orgasmic energy in the air. Responsible, given how many sex boxes he was selling.

Eventually he got to the point where he saw UFOs cropdusting us with “orgone energy” and would stand on his roof blasting them with his water cannon, assumedly wearing a tinfoil hat.

But, crazy or not, he had some neat ideas.

Way before the UFO thing, Reich wrote a book called Character Analysis. “For Reich, character structure was the result of social processes … Reich proposed a functional identity between the character, emotional blocks, and tension in the body [Wikipedia].”

Reich theorized that character is born first out of emotional responses to stimuli (internal), then physical responses (external).

He called your character archetype–or your feeling stagnant in everyday routine–The Trap. He was a Marxist and generally unhappy dude, so his outlook was a little bleak, but bear with me:

“It IS possible to get out of a trap. However, in order to break out of a prison, one must first confess to being in a prison. The trap is man’s emotional structure, his character structure. There is little use in devising systems of thought about the nature of the trap if the only thing to do to get out of the trap is to know the trap and to find the exit. Everything else is utterly useless.” [Reich, pp. 470-471. From The Murder of Christ: The Emotional Plague of Mankind, 1953.]

“The trap” sure sounds an awful lot like the emotional state of a character in Act I. And the focus on the character’s internal journey is exactly what we’ve been pushing for. Eureka! We could superimpose a simple shape over the top. I suggest a cube. I don’t think cubes have been done yet. But what should we name it? Ah, yes. The Orgasm Box.

It’s got everything we need to build a model based on the human condition: a man in a hole, palpable anxiety, competing schools of thought, overzealous use of ALL CAPS, a journey to self-discovery riddled with mistakes, an ambiguous ending, and so much more! We’re going to make millions.

OK, all joking aside, there’s actually some good stuff in here. What Reich does is position the problem through the lens of the character’s internal logic. This is similar to the hero’s journey where the main character must make choices on their path that compel them to the next stage.

MAN IN TRAP: Our hero is “stuck” in their everyday routine or stunted by a flaw. He has to want to get out or he’ll never make a move. But before he can even realize he has a problem, he probably tries some things: tries to make himself feel better about the cards he’s been dealt, dreams about what it would be like with a different life, prays on it, maybe even invents an alternate reality or persona different from himself to cope.

CONFESSION: When none of that works, maybe he’ll admit to himself something needs to change. But that still doesn’t mean he’s ready to act. (We call this moving from precontemplation to contemplation). At this stage, he becomes a little more desperate for things to be different, but doesn’t yet see himself in control of his own destiny. He starts preparing for the change—dipping a toe in—but he still can’t conceive of a world different than his own reality.

MOTIVATION: Then, he figures it out. The world doesn’t need to change, he does. This is a big step. And he faces consequences for “waking up.” His friends and family don’t understand. Maybe an antagonist tries to stop him. Once he does make that commitment, there’s nothing that can hold him back, but boy will they try. If he’s cemented his internal change, he’s equipped to move forward; if not, he’s gonna’ die (literally or spiritually).

ESCAPE FROM THE TRAP: Once he’s out, everything becomes so obvious. How could he ever have been stuck in a prison of his own design? (The audience is also on the outside. To them, all is clear.) There’s no way he can be trapped again because he has changed physically and psychologically.

This heuristic shares commonalities with Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, the Hero’s Journey, etc.—Remember, all stories come from the same basic structure—but with one main difference. We’re not just watching a character take the steps, we’re thinking deeply about the inner development that results in those steps being taken.

The human condition model (aka The Orgasm Box™) can be applied to any genre:

Love (romcom)—Moonstruck, Groundhog Day

Death (horror)—SAW, The Ring

War (action)—The Matrix, Braveheart

Aspiration (sports drama)—Remember the Titans, Rocky

You might also take the approach of placing multiple “trapped ones” in conversation: the guy who wants everything to remain status quo, the one who thinks everything will be better once they get through it, the one who JUST WANTS TO GET OUT OF HERE, the peacemaker. What happens to your story when you put all those people in an escape room together? What character truths come out? Who changes, and how? Do they all make it out alive?

Ideally, you get the joke and aren’t currently trying to pre-order my new screenwriting book on Amazon. The lesson is not to put your story into a prefabricated model and see what pops out the other side, but to take a more holistic approach to the narrative if your characters are feeling thin.

One possible way to do that is to ground your plot points in the psychological evolution of your characters. Another is to dig into whatever element of the human condition you are trying to tackle and consider whether you are effectively communicating your thesis, or if there is more to explore.

Use ideas from other fields to inform your writing. And, if all else fails, you can always collect orgasms and shoot them into space.

*Feature image by Sdecoret (Adobe)