Think Small

As screenwriters, we’re used to thinking big.

We work on features that track a character’s life-changing arc, moment by moment. We develop television ideas with complex plot lines that will span at least four seasons. With the advent of comic book cinematic universes, it’s not uncommon to think of your stories as one component of an even larger timeline.

This is part and parcel of being a screenwriter. You must learn to think of story within a 30-minute framework, a 60-minute framework, a 90-minute framework—and possibly beyond.

But there is a huge drawback to constantly working in long-form storytelling, and it has to do with the nature of the medium.

For a script to feel like a story, it has to be built on a solid foundation of storytelling principles. You fumble the set-up, your script doesn’t feel like a story. You fumble the middle, your script doesn’t feel like a story. You fumble the ending … you get my point. Before you do anything else, you have to get your story right.

However, the necessary work involved in getting your story right can leave little room for creative expression.

We all know it’s foolish to spend time on that snappy voiceover when the character speaking it doesn’t have a clear motivation. We all know that experimenting with flashbacks and flashforwards isn’t going to fix a premise that barely has the legs for a short film, much less a feature.

It’s not that you can’t take risks or that anyone is stopping you from taking them, but elements like character, structure, and theme naturally (and rightfully) take priority over pure artistic play.

While any development exec will be happy to see you forget about that voiceover and finally work on the real issues in your script, this mindset can be dangerous in the long run. If you get too accustomed to putting voice and style on the back burner, you’ll never get a chance to develop it.

You’ll have a story, but it won’t be yours.

It’s the problem I’ve been up against for years. I can analyze a script’s structure or track a protagonist’s arc with the ease of a genius hacker in a heist film (OK, genius is a strong word), but ask me to describe my style in a fellowship application, and I’m staring at that blinking cursor for hours.

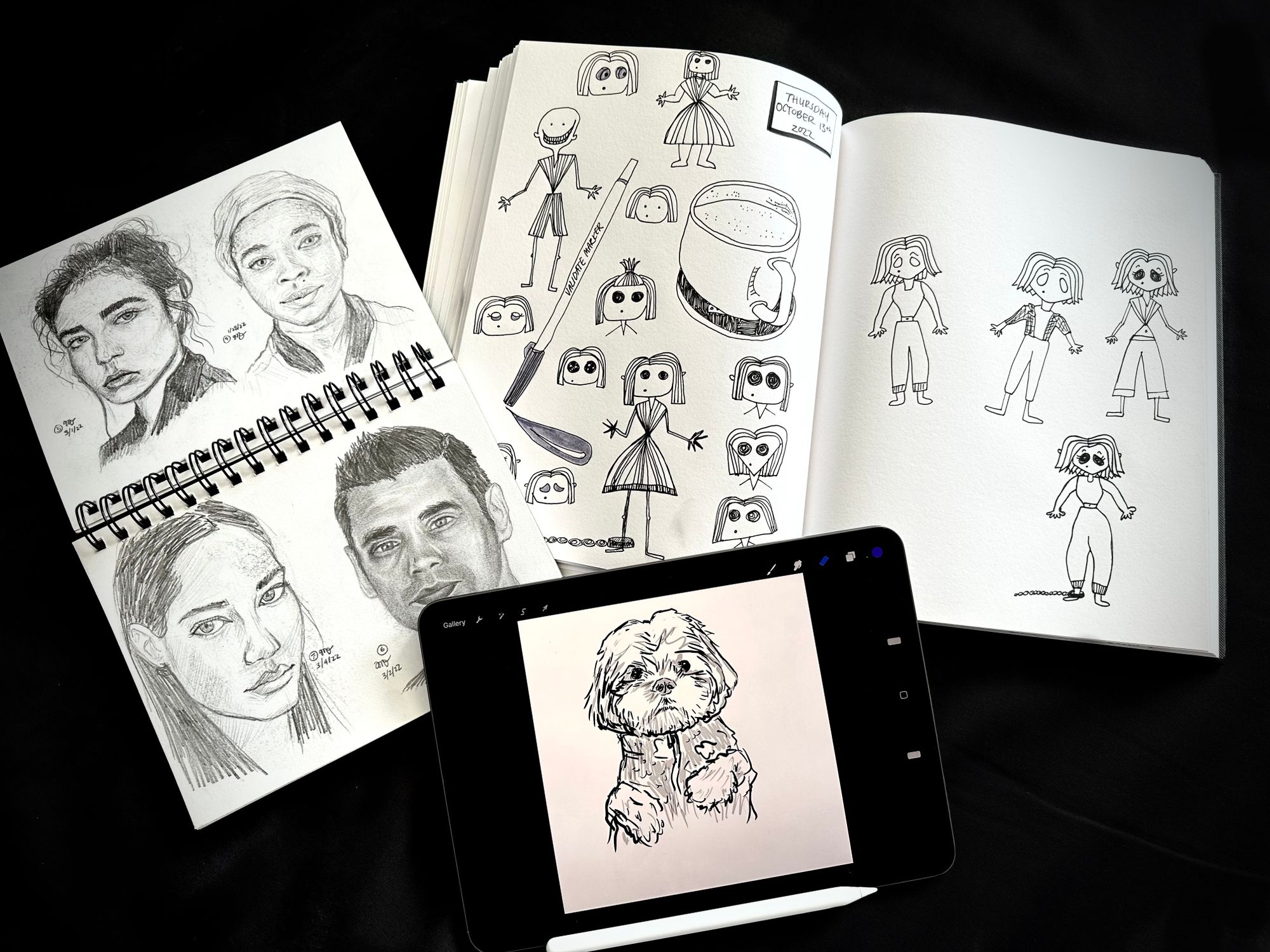

Of course, I didn’t think this was my problem. I just thought fellowship applications were hard and that "style" is a tacky word, anyways. It was only once I started drawing again that I realized how much I had stilted that artistic side of me.

I don’t know exactly what led me to pick up my sketchbook again. Maybe it was the stress of daily life and the hope that drawing could relieve some of it. Maybe it was a secret desire to reconnect with my art school days, a time where I didn’t feel immense pressure to make it in Hollywood. Maybe it was an internal drive issued from Destiny itself, guiding me to a better path.

Whatever the reason, I started a daily practice of filling white pages with lines and color. It turned out to be incredibly healing—there's an importance of having a secondary artistic hobby.

Then, after a few months, I became obsessed with the idea of turning my drawings into short films. I closed my sketchbook and opened Final Draft, where I poured my linework and color discoveries into a handful of short scripts, some of them as short as a single page.

I knew immediately there was magic in these pages. Not in the storytelling frameworks per se, but in the visual language I had transformed into my own unique writing style. It was the first time in a long time that I read my own writing and recognized me in it, as clearly as though it were a handwritten scrawl instead of Courier font.

When I got back to work on my feature, I naturally wrote with my old-as-time-but-newly-discovered voice. In terms of its merit, I can’t exactly play development exec to my own script, but I can tell you it has that same magic.

Well, it’s been some time since I last picked up my sketchbook or opened my desktop folder of short scripts, but I do think there is a lesson to be gleaned from this experience, and it has less to do with medium than it does scope.

While drawing obviously helped strengthen my visual sense as a writer, its biggest gift to me was providing the space to approach a single blank page at a time. In this tiny, contained sandbox, I could take all the risks I wanted without the stress of building something that has to stand.

On a daily basis, I pushed myself to think differently. I wouldn’t hesitate to combine random images, creating meaning out of seemingly disparate objects. I’d experiment with color palettes, seeing what went together and what didn’t—and then asked myself what was more exciting to me: harmony or dissonance? I played. Without bashfulness or restraint, I played.

Drawing didn’t heal me. Risk taking did.

I believe that my shift into short scripts was my inner artist’s way of testing whether I could take these same risks in my chosen medium. It knew I wasn’t afraid of my sketchbook, but I was afraid of the keyboard. Once I proved I could take my sandbox with me into Final Draft, my desire to work in long-form storytelling came back.

For any writer who feels disconnected from their work, I heartily encourage them to carve out time for a small-scale project, whether that’s a poem, a drawing, a short story, or even a song.

Sometimes, in order to find your big swings, you have to think small first.

*Feature Art by Michelle Domanowski