What Makes a Script Great?

I love movies. I always have. I grew up during the 1980’s and 1990’s, and during that time period, the cinematic landscape was rich with the types of films we don’t really get anymore. Tastes evolve, trends change, but one thing stays the same—it always starts with a script.

Hopefully, a great script.

There are so many ingredients that make up a “Great Script,” and it takes an enormous amount of time, dedication, and self-preservation to get something completed that you can truly believe in. Or maybe not—because judging by some of the submissions I’ve read over the years—it’s as if people sometimes don’t have any idea what they’re doing, and yet they firmly believe that they do. In that regard, the cause is most likely lost; it’s tough to reverse course if self-delusion is the name of the game. But in many instances, screenplays do nothing but get stronger and more evolved and more satisfying after countless revisions have been made, and after all creative options have been exhausted.

I’ve never written a screenplay. So, what makes me qualified to tell those who have written their screenplays that they are good, bad, or indifferent? Art is nothing more than a series of opinions, and the fact that people compensate me for my words and my opinions, means that they value what I have to say, and they trust my instincts. I’ve read countless screenplays and have viewed thousands of movies. Many other people have, too. But not every person is consumed by cinema on an all-day, every-day basis. From the early morning and all the way until it’s late at night, stories and movies and trailers and scripts and images are floating around in the brainpan, and when you see life through eyes that are calibrated for 2.35:1 anamorphic widescreen, you can’t help but compare everything you view on the big screen to all that occurs during real life. The old cliché that life imitates art (and vice versa) reveals its beautiful head every single day.

When I first started reading screenplays in an academic fashion, I was working at Jerry Bruckheimer Films (JBF). I’d relocated from New Hampshire to Los Angeles during my junior year of college, and my dream-come-true experience of interning at JBF led to my first paying industry job, immediately upon graduation. I received a crash course in all areas of production, and I saw my idol working at the absolute peak of his powers. Films like Black Hawk Down and Pearl Harbor and Remember the Titans and King Arthur and National Treasure and Bad Boys II and Pirates of the Caribbean and many others were all being prepped, shot, or posted during my time spent at his compound, and the flurry of activity in those offices was equal to nothing I’ve ever seen anywhere else. And most importantly, I got a chance to read scripts. TONS OF SCRIPTS. Scripts that never got made, some that got made and share no resemblance to how they were initially conceived, some that cost extraordinary amounts of money to commission, and others that, quite simply, weren’t up to par.

It was overwhelming, as I’d only read a handful of major screenplays during high school and the first couple years of college, but there I was, getting handed drafts of Bad Around the World (the United Kingdom would have never been the same …!) and Affirmative Action (wish that one had been made) and Gemini Man (if only they’d use the early drafts!) and countless others. These were the days of the high-concept spec script, the big splashy sale.

The various executive assistants taught me the basics: how to retain bits of information in a fast-paced manner, how to know within the first few beats whether or not the writer had a confident grasp of the basics, and how to “lose yourself in the writing.” I remember one of the assistants using those exact words—it’s all about giving yourself over to the process of experiencing someone’s artistic creation, and that plays a large part in how someone potentially connects with a piece of material.

So, what makes a script a successful endeavor? I’d argue that it’s a combination of many things, but for me, the most important items always come down to these:

- Am I in the hands of an assured writer who absolutely knows, front and back, the story they are telling, and are the characters compelling? Not likeable—not everyone needs to be likeable in the movies, contrary to popular opinion—but compelling.

- Are they taking part in action that makes me want to continue reading?

That’s the goal. Those, I think, are the two biggest things that immediately stand out to me when I read a spec script.

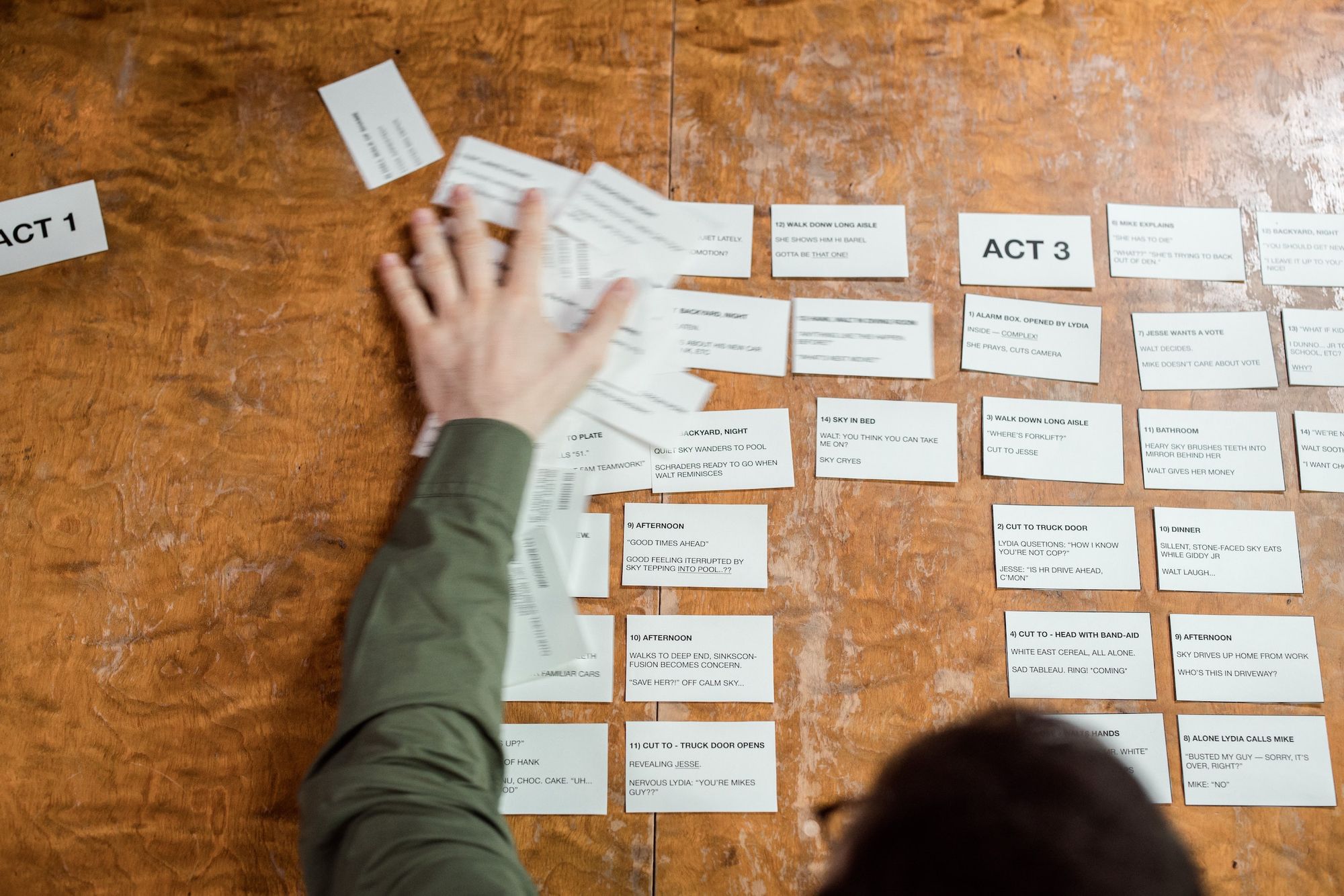

And along with that—comes perhaps the biggest thing I can think of: THINK VISUAL.

Far too often, writers are insistent upon featuring scene after scene of either boring exposition or back-and-forth dialogue. Movies are a visual medium, and ultimately, it’s a director’s medium. True, everything starts on the page, and a film is, more often than not, only as good as its screenplay. But for a writer to be consistently successful and to attract strong filmmakers, thinking on purely visual terms is of major importance. I’m not asking for silent screenplays, but, I will say, some of the most memorable items that I’ve read in recent years contained a limited amount of actual spoken dialogue.

Relying on visual storytelling allows the reader/audience to invest themselves into the material on a totally different level, rather than having everything explained to you with words. Be big and bold and dynamic with your choices when coming up with ways to visually express the narrative and the emotions that your characters are facing.

Oh. Commas. Please know how to use the comma. A lack of commas, or the mis-use of commas, can be an almost immediate deal-breaker, at least for me, when reading and assessing a screenplay. Incorrectly used commas (or un-used commas) can ruin the flow of the reading experience, cause the reader to have to double-back on themselves, and can turn context around in unintended ways. In general, solid grammar, punctuation, and spelling is of critical importance, as those stories you’ve heard of over-worked development execs and their super-over-worked assistants tossing poorly-worded screenplays into the trash are very much real. They don’t have the time or energy to waste on scripts that are marred with amateurish mistakes, and one of the best things that can happen for someone who is a reader of numerous scripts per week, is to receive submissions where it’s clear that the writer took the time to edit and clean up their work. If you don’t have the patience for the editing process—I totally understand that. But hire an external reader and have them assist you. Your final product will thank you for the attention that it deserves.

And ultimately, it’s not about the story, it’s about the characters. I’m sure you’ve heard someone say this phrase, when asked about a particular movie: “Yeah, you know, I knew nothing about that world, and to be honest, I wasn’t sure if I’d like it, but damn, it was great—the characters were just terrific.” You never hear it the other way around. Not many people want to spend time with poorly developed characters that aren’t fun to be around. Audiences will surrender themselves to the same narrative formulas and templates, just as long as you bring fresh characters to the table, and provide them with a new spin on classic scenarios.

And my biggest piece of advice would be this—if you love writing—never stop doing it. Write a little bit, each day. Read other people’s screenplays, and seek out classics from each genre. Trade scripts with other newbie writers and give each other notes. Pay for a round of professionally crafted feedback from unbiased sources. And be prepared to face rejection and silence. That’s part of the game. But you have to be persistent.

Unless you’re the nephew of an Oscar winner or you catch the luckiest break imaginable, it takes more than talent to succeed. It takes an unwavering sense of spirit and an almost ridiculous degree of intestinal fortitude, with an eagerness to learn every step of the way, and to face potential challenges at nearly every turn. But the rewards are worth it, especially when you can say to yourself that you’ve done everything you possibly can to tell the best possible story.

*Feature photo by Ron Lach (Pexels)