Whose Story is it, Anyway? POV in Storytelling

Nick Carraway. Scout Finch. Ishmael.

These three characters narrate the acclaimed literary works The Great Gatsby, To Kill a Mockingbird, and Moby Dick. Their points of view are what the readers rely on, not just for the ebb and flow of the narrative, but how to perceive what’s occurring. Their close proximity to the main characters and events not only gives their job as storytellers immediacy, but it makes them the authority to the reader. They’re as reliable as a narrator can get in fiction.

Not surprisingly, these three famed narrating characters also serve as moral commentators on the actions in their stories. The moralistic Carraway loathed the privileged elite that were Gatsby’s contemporaries. Youngster Scout was a fairer citizen than those trumping up charges against a wrongly-accused black man in town. And Ishmael was the kind of working man who suspected Captain Ahab was off his rocker almost the moment they set sail.

In film, where narration is supposed to be a no-no, the author’s POV on events is still in plain view, even if there’s never a voice-over. The way the characters are written, what they say, and how they act all showcase the author and, very often, their moral inclinations. No matter what the script, the author sends the audience a message: this is what I think, why I think so, and why I want it to matter to you.

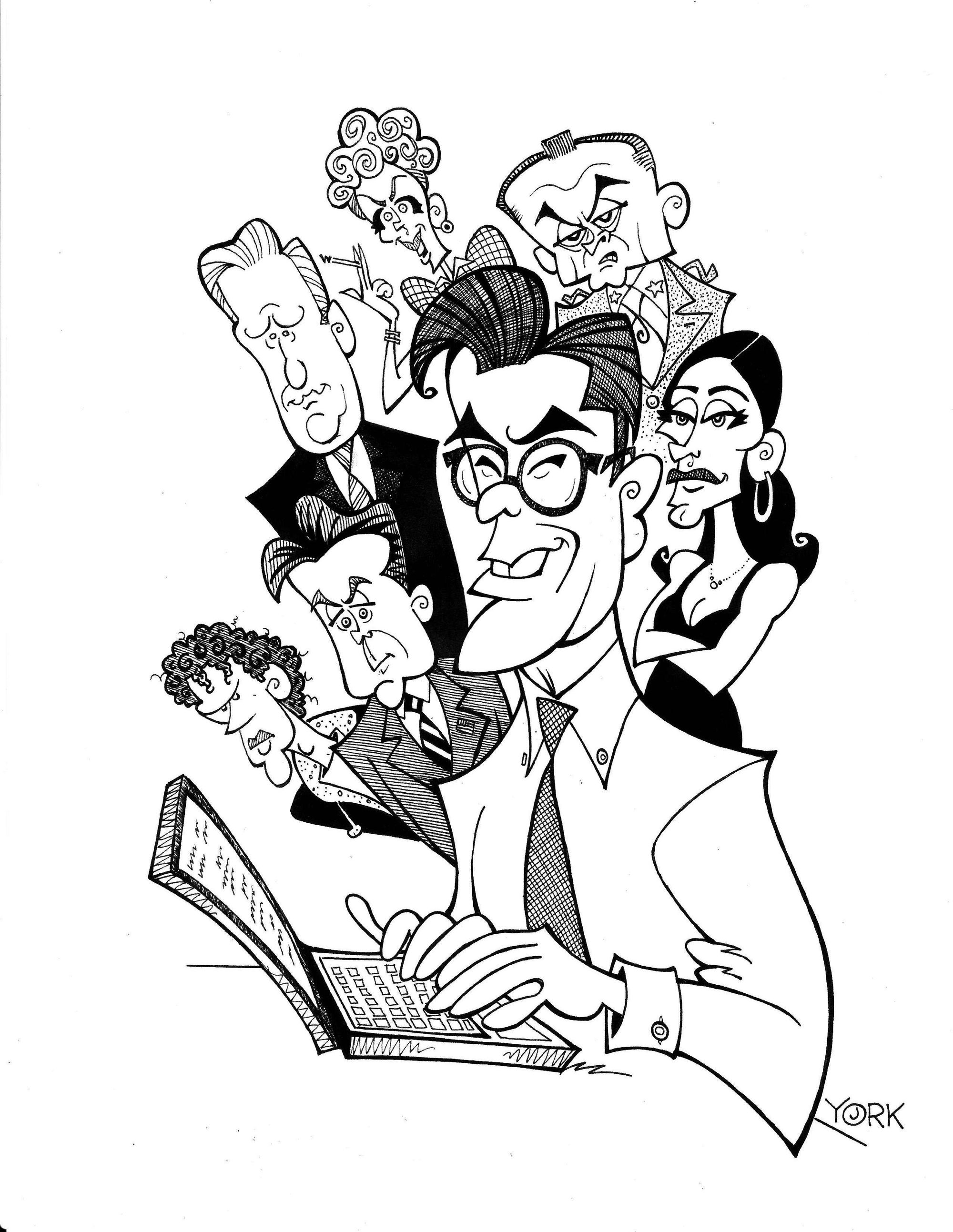

Take Aaron Sorkin, for example. Sure, the award-winning screenwriter’s progressive sensibilities are clearly on display in everything from A Few Good Men to The Newsroom to Molly’s Game, but arguably the most intriguing factor in his prose isn’t his moralizing, but rather, who he’s moralizing to. Sorkin rarely hectors the average Joe. Instead, Sorkin’s targets onscreen are those in power who abuse it be they politicians, network executives, or even social media upstarts. (Sorkin had little sympathy for anyone in The Social Network, especially Mark Zuckerberg.) And those he’s shaking by the lapels are those high up on the food chain who have the power to thwart those abusing theirs.

That’s why Tom Cruise’s Navy lawyer is the one who must take down Jack Nicholson’s corrupt colonel, why Jeff Daniels’ cable anchor is the only D.C. giant who can challenge the political elite, and why Jessica Chastain’s gambling impresario is the only one who can emasculate all the corrupt men entering her den of iniquity. Sorkin’s POV is that those on the inside are the ones who must do their damnedest to right the ship. He’s not one for David’s taking down Goliath’s. He's too savvy to be another Frank Capra.

In Sorkin’s most recent hit, Being the Ricardos, a biopic about the making of "I Love Lucy" in the 1950s, he makes it crystal clear who the real enemies of Lucille Ball (Nicole Kidman) are. They’re not the batch of insecure writers and costars she’s corralling, and it’s not her philandering husband, Desi, either. No, the greatest threat to Lucy are the network hacks who continually try to screw up her show. Sorkin’s POV has little regard for those in power in America, but he tells us over and over again that those who can change it aren’t little giant killers; they’re other giants. That’s his POV.

It's fun to watch a film or show and discover what it has to say and why. Paul Schrader almost always writes stories about little guys being swallowed up by corrupt America. That’s his POV. Greta Gerwig believes in women outwitting the patriarchy. Wes Anderson believes in quirky individuals striving to be heard. And Dick Wolf knows that American justice resembles a sausage factory—watching it in action is ugly business.

Those are the POV’s of four vaulted creators in show business. And every writer, be they an Oscar-winner or novice, needs to take a stand on whatever issue that is present in their work and ensure that comes across clearly to the audience.

This is not to say that every film or show has to have neon signs screaming out what the message is, but they need clear points of views. The easiest way to do so is by determining the obstacle keeping the hero from achieving their goal. Is it someone with power? A company? A country? Geography? God? Who or what is the antagonist? Then, once a writer has that figured out, everything his or her hero does is about trying to conquer whatever is standing in the way.

It helps to have a likable protagonist, but even if the hero is hugely flawed, they should be more relatable than the villain. Robert Downey Jr.’s Tony Stark may have been a glib and egotistical douchebag a great deal of the time, but he was a saint compared to the villains he went up against: corporate bigwigs, megalomaniac robots, and purple-skinned galaxy-enders.

Stakes are always vital to any drama, but not everything that the protagonist is trying to accomplish need be life or death. Sometimes, what an author will try to communicate is to simply live and let live. Not everything is a test of moral courage, like in Sorkin’s world. Sometimes, a music teacher just wants grade schoolers to have fun, like in School of Rock.

Occasionally, a chef just wants to ensure his customers enjoy his food, like in Big Night. (And without ordering a side of pasta to go along with the risotto.) And sometimes, an old man wants to live independently with his cat a while longer before he no longer can. That’s Harry & Tonto.

Generally, a writer expresses themselves best when they agree with the protagonist’s quest and find nobility in the actions required to achieve it. Stories where perspectives change and the author’s POV shifts as well are trickier as they muddy the waters. Such tropes used to be considered a storytelling faux pas back in the day, but that changed in 1960, with Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho.

In that game-changer, the filmmaker killed off heroine Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) halfway through the film, changing the main character and POV from her to seemingly innocent bystander Norman Bates (Tony Perkins). It wasn’t until the final 15 minutes when audiences discovered that it was the not-so-innocent Norman, masquerading as his mother, who killed off Crane, but by then, Hitch had changed what a storytelling POV could be forever.

Few filmmakers dare switch up perspectives, like in Psycho, but David Fincher did it in his adaptation of Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl in 2014. He kept her book’s conceit where the first half of the story comes from the POV of a hapless husband accused of murdering his wife, before the narrative shifts to her perspective of escaping a dead marriage. Fincher’s film succeeded, just like the book did, because ultimately, both of the main characters’ perspectives were immature and selfish, and as they chose to stay together, their perspective’s merged, too. It was a case where the filmmaker and original author were sneering at their awful protagonists, not agreeing with them. Still, this is rare in storytelling.

Having multiple POV’s is even rarer. It worked in Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon back in 1950, but struggled in a similar film just this past year called The Last Duel. Both films concerned a rape and the recounting of such a heinous act by varied parties involved. But while Kurosawa’s film let the audience fill in more of the blanks and be the final arbiters, director Ridley Scott and screenwriters Nicole Holofcener, Matt Damon and Ben Affleck hedged their bets in the final reel.

The events of the rape are shown three times, with subtle differences in actions, words, and motives giving rise to the three angles. But as the wife’s story is told at the end, a title comes up that tells us that her story is the truth. Why show different takes on the story, and show the rape three times, if you’re not going to negate things in the last reel? The POV there was conflicted … until it wasn’t. But it felt like an easy out when it was set up to be a complicated “he said/he said/she said” type of story.

In such a case, the POV felt squishy—first one thing, then another, and it seemed to reflect more of a ploy that the perspective of the storytellers. When it comes to POV’s, it’s best if they leave the audience working less to understand what the artist is trying to say, and more time considering how they feel about such a message.

And if a writer is going to present his POV in those big, neon letters, becoming almost strident in his or her moral clarity, then one should hope to be as clever as Sorkin is when he gets on his soapbox. Consider the character of the idealized American president Josiah Bartlet in seven seasons of Sorkin’s legendary TV drama The West Wing. The show presented the Commander-in-Chief as an almost saintly leader, advocating righteousness at every turn. Still, Sorkin mixed in characteristics that helped bring nuance to Bartlet’s and make his moral POV all the more fascinating.

For starters, Sorkin made the prez a practicing Catholic, hardly a religion in public favor at the time in the 90s, but it helped make Bartlet’s piety grayer. Second, Sorkin made the president extremely vulnerable by suffering from MS. That not only raised the stakes but explained some of the ill Bartlet’s now-or-never application to events. Finally, Sorkin wrote Bartlet as often temperamental and not afraid to hector God. Such dimensions didn’t change the Sorkin/Bartlet POV, but it did add empathy to the sanctimony and made such piety more palatable.

Even if you don’t always agree with Sorkin’s politics, you have to admit the guy knows how to make his POV clear, heard, and compelling. And from any writer’s perspective, trying to tell their story, that’s saying a helluva lot.