Why Grumpy is Great On Screen

The great French composer, Claude Debussy, once famously said, “People don’t very much like things that are beautiful. They are so far from their nasty little minds.” He also wryly stated, “The trouble with the opera is that there’s always too much singing.”

What Debussy was getting at with both quotes referred to an essence of grumpiness in the human condition. Call it a negative attitude, or that of a misanthrope, the fact is that most folks feel more comfortable finding the fault in our stars, not the illumination.

And that’s great for drama. After all, stories thrive on problems. Something that needs to be overcome or conquered has informed more books, plays, and screen stories than all those musical notes Debussy was complaining about. And most problems in life, or in any story, generally are negative.

In life, we don’t like our boss, or we want a better car, or wish that our crush would dump their significant other. Hopeful, yes, but informed by negativity. In Hollywood, the Nazis need to be stopped from getting their hands on the Lost Ark, my best friend needs to be kept from getting married to someone else, or how does a transit cop stop terrorists who’ve taken subway passengers hostage in NYC?

All problems, all negative things to overcome.

And yet, in drama or comedy, such problems are also opportunities for any protagonist to prevail. (One man’s meat is another man’s poison, as that saying goes.) That is what makes narrative exciting—defeating the odds and returning as the conquering hero.

But here’s where writing about such problems/opportunities get truly interesting … what if the hero tackling such negatives is themself a very negative person? What happens when the lead of your story is not a happy camper but instead a grumpy one? How does that color the adventure? Darker shades, for sure, which will always add complications, nuance, and the unexpected.

Wise writers have often followed such a template in their efforts for the big or small screen. Down-in-the-mouth grinches play, creating immediately interesting characters. Think of the movie stars who’ve cultivated grumpy personas like W.C. Fields, Humphrey Bogart, Bette Davis, and Walter Matthau. Even romantic leads like Hugh Grant, Sandra Bullock or Harrison Ford often have acted the contrarian versus Cupid.

If you’ve seen anything that Matthau was in, he was all but the poster boy for grumps. (Heck, his last big hit was entitled Grumpy Old Men.) Whether he was arguing with Felix Ungar in The Odd Couple, or with the subway terrorists in The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3, or his old vaudeville partner in The Sunshine Boys, everything Matthau performed was informed by a world-weariness that he earned by being a New Yorker and a resident of this oft-disappointing planet.

The same could be said of Harrison Ford, too, albeit more galaxy-wise. His Han Solo shot first because he was a malcontent, and as Indiana Jones, a very reluctant hero. Indy spent as much time complaining about snakes, blabby partners, or sharing lovers with his father, as he did in saving the world.

On television, Dr. Gregory House was one of the all-time Grade A grumps. So were Archie Bunker, Fred Sanford, Tony Soprano. Don Draper, and Raymond Barone. These characters resonated with audiences despite such negative traits because they were still relatable.

Indeed, we might have had the same melancholy take on matters if we were in their shoes. At the very least, they were enduring as well as endearing because they were humorous, vulnerable, and even pitiable in their disgruntled world view. Such characters give actors, filmmakers, and especially writers, a lot to work with as they bring so much more to the party than Pollyanna’s do.

What makes grumps especially interesting as protagonists can be found in two vital ways worthy of consideration by any creator.

First, there is a fascinating backstory waiting to be told of why the grumpy protagonist is that way. It’s the key to understanding why they behave as they do and what that means for their adventure.

Two, the transformation of a grump into a hero is inherently more dramatic, especially if they’ve been converted from their tendencies to be self-loathing, apathetic, and even selfish. This is perhaps the greatest attribute of Charles Dickens’ beloved tale A Christmas Carol. Scrooge is very possibly the king of the grumps. It also explains why this story has been remade so many times on the big and small screen—it never gets old and ol’ Ebenezer’s transformation is beckoning all of us to try harder.

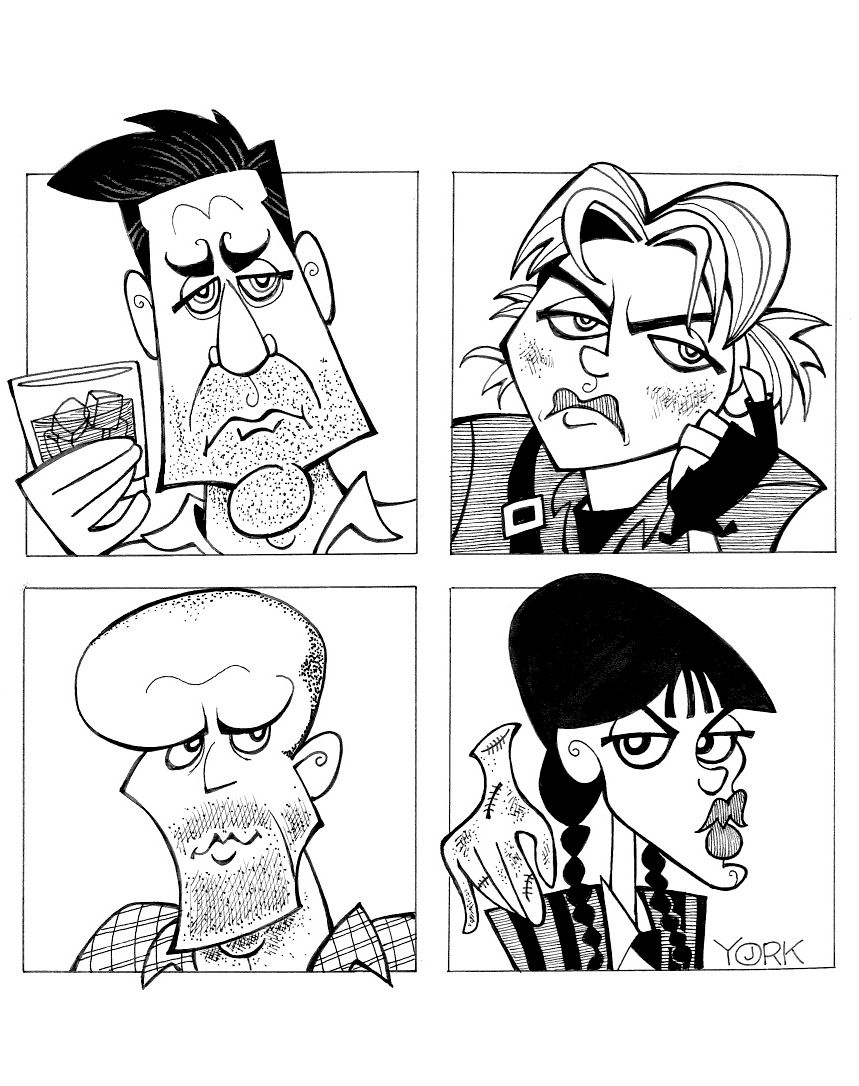

There are likely more positive, gung-ho heroes gracing film and TV overall, but since this century began, and the crazy ups and downs it has encountered, our collective psyches have grown more misanthropic. Our malaise has ended up yielding plenty of characters who in sunnier times would most likely have been the villains in a story. I’m thinking of characters like the bitter student that is the heroine Jenna Ortega (pictured) plays in “Wednesday.” Then there’s the character of Andrew Cooper played by Jon Hamm (pictured) on the series “Your Friends and Neighbors,” showcasing a malcontent who goes from fired hedge-fund manager to high-end thief. Then there’s the carping duo of Jean Smart and Hannah Einbinder playing frenemies on “Hacks.” If being so vicious to your coworkers is what it takes to make it in show biz these days, good luck to all those in Tinsel Town.

Not to be outdone by such cranks on TV, grumps are ruling the big screen often as well. Look at how big a deal Florence Pugh’s Yelena Belova (pictured) has become since fronting the Thunderbolts film. (Oh, I’m sorry … The New Avengers.) Every movie made by Jason Statham (pictured) showcases a reluctant hero pulled into action by some problem that he will gripe, grumble and groan about in between chops, socks, and roundhouse kicks. Even Demi Moore, in her big comeback year of The Substance, played a variation on the bitter, resentful grumpy characters she has played her whole career, from A Few Good Men to G.I. Jane to Mr. Brooks.

One of the great things about such characters is that they tend to be more unpredictable and that presents their creators with greater opportunities to zig when most stories zag. Even if they succeed, they may not act any happier. That makes for a more interesting ending even.

If the hero wins the love of his or her life, can they keep the good times going? Such worries may keep those misanthropes in bad moods for years and wouldn’t that make for a more fascinating sequel? And what does the protagonist do for a follow-up if they end up winning the new business pitch, saving the family farm, or keeping the world out of the hands of a fascist—what do they do for an encore?

After all, grumpy people are seldom satisfied. And the more they whine, kick up a fuss, or disengage, the story can only become more unexpected. And eminently watchable.

Such contrarian takes add up to more surprising storytelling, and we could all use more of that when shilling out our entertainment dollar. Such protagonists don’t just play with audiences’ expectations, but they also are playing more unique and dissonant chords. And those flats and sharps always make for a far more interesting song don’t they, Monsieur Debussy?

*Feature image created by Jeffrey York