Access

Mum was always an addict. She wasn’t into gambling or alcohol, but lottery tickets, the penny machines at arcades, bouts of manic shopping, and back to back episodes of Downton Abbey. She cheated on her diets with large stashes of chocolate that she would devour and instantly regret. She chewed on her inner cheek when her credit card bills came in, and snickered at her impulse buys.

Mum always needed just one more, her skin flushing and eyes gleaming like a child. We would inevitably be late if we had to stop for petrol. Can’t resist a little flutter, she would say, grabbing a handful of shiny cards at the till. Flakes of metallic rubbings would float down into the footwell as she scratched away with her fingernail, too impatient to look for a coin.

She liked to wait a beat before doing the last one, relishing in the potential. When I was young, she used to let me do the last one, inviting me into the bubble of excitement. As a teenager, it became just another vaguely embarrassing habit.

We never had little treats like this growing up, she would remind me. We couldn’t afford anything, not even new socks. The thought of darning and passing down old socks from sibling to sibling was completely foreign and, frankly, gross to me. Yet it was the way of life for Mum and my aunts and uncles, and one they told me about—often—at family functions, a giant, unorganised mess of six siblings and their respective families joining up to tell the same old stories once a year or so.

Uncle Bert was the oldest and loudest, rocking back on his heels and jabbing his finger in the air as he commandeered the conversation with Scouting tales that bored my ears off. Aunt Beth loved to tell me how she had to tie her knickers together and padlock them at the end to stop Aunt Sylvia from stealing them. As an only child, I didn’t even have to share my bedroom.

So I knew when the product hit the market, Mum would be one of the first in line. In the beginning, it was rumoured that even celebrities were doing it. Can you imagine, she said, living like one of them? Even for a moment? She couldn’t resist. Mum wasn’t the type to ask a lot of questions. Like the unerring trust the elderly have of doctors in white coats, the product was popular and official enough to warrant her complete faith.

The first memories to go were the ones of Dad.

Don’t worry, she told me, you’re not in any of them. I wouldn’t dream of doing that.

We decided it was best to pick both good and bad memories of him. I didn’t want her hating Dad, but I also didn’t want them back together.

The tricky part was choosing memories that would be worth selling. The welcome pack outlined the basic idea: the more in demand, the more you would get for them. That skydiving memory would cost more than a few dull Sundays in a two-bedroom flat. People wanted passion, excitement, love, anger, violence, sex; things you can’t always ask for in real life.

So she had to make them last, we decided. No more than one a month, and any major events had to be discussed. She agreed and wrote her promise on the whiteboard in the kitchen next to her motivational dieting quotes.

She waited until I got home from school for the first session. As I opened the door, she was there in the hallway, pacing, wringing her hands, and chewing the inside of her cheek. There was an odor of cigarettes and a strong lavender scent that almost covered it.

We sat together in the living room, and I watched it happen. I could see her heartbeat in her neck, her eyes dancing in REM, and feel the rapid pulse of her wrist in our firm handgrip. I didn’t know it then, but I was watching the beginning of an addiction seeping through her blood, spreading further and further with each thump of her heart.

For her first memory, Mum had picked something that was as far removed from her council flat working-class childhood as possible. It had cost a lot, but she reasoned she could never afford to go to New York for real, so it seemed like a good trade. A few hours in the life of a Manhattanite was the polar opposite of hers: rich Upper East Side apartments with their white-gloved doormen; crowded Chinatown streets full of delicious aromas and vendors selling knock-off designer items; smatterings of languages and dialects that hit her ears as she rounded corners or descended into subway stations. She would rewind again and again the moments she could catch glimpses of the Empire State Building or the Brooklyn Bridge, and for some reason, crazy subway dwellers that yelled random obscenities and pushed trolleys full of crap.

Her eyes remained open yet glazed over as she accessed, clapping her hands together and laughing out loud as she described the strange things she was experiencing. Her cheeks took on the familiar rouge hue, and from certain angles, she looked completely manic.

The next time she did it, she had a sneaky peek before I got home. I slipped my school bag from my shoulder and let it hit the ground, snapping her out of her trance. I just couldn’t help myself, she explained, looking hyper and guilty at the same time.

As her memory bank became richer, our conversations became more one-sided as she exhilarated in telling me the details of her mental excursions. My mother, who grew up in a two-up two-down in Northern England, now lived a wealth of exotic, dangerous, and glamorous lives, all in her mind.

She delighted in practising snippets of foreign languages she’d heard, or looking up Google street view images of places she’d been to, pointing out all the hidden details to me as if she were a local. Anniversary trips she’d taken with Dad were traded in for more exciting and romantic ventures to countries she’d never been to, without thinking about why they were for sale in the first place.

I quickly began to recognise the look her eyes took on when she was accessing the memories, like the insidious beginnings of glaucoma creeping in from the outer edges of her irises. While she was counting down the days until I was the legal age to access, I was beginning to have my doubts.

After a while, she stopped waiting for me altogether. It stopped being our shared thing and became just her thing. Every time I walked into a room, I knew she had been accessing a second before I entered. Our evenings of watching trash telly together and playing our made-up advert game during the breaks stopped being fun when I could sense her flipping over to her alternate reality instead.

I told her she should think about quitting, cooling it for a while. I’m fine, she told me, slightly irritated. Let me have a little luxury in my life. God knows I’m owed it.

So I did, because a large part of me felt that she was right. My childhood memories of trips to Skegness and Tenerife might not have been much, but it was more than she ever had. The other part of me—the cowardly part—didn’t want to face an argument with her. She had always been much better at arguing, and with her more regularly occurring moods, she was becoming irritable and tetchy.

When she was like that, our fights could last for days. I didn’t push it.

But the swaps became more and more regular and, looking back, it was probably more frequent than I knew even then. I could feel the bond between us fracturing and splitting, like an electrical cable that has seen too many years, that has been bent and twisted too many different ways.

Sundays had always been our time together. They had started one morning a few years ago when I was feeling sick. Mum dragged both of our mattresses into the living room, closed the curtains, and we watched TV in our pyjamas all day. It became a regular thing, our own little world that wasn’t like the one everyone else lived in, where adults never stayed in their pyjamas past 10 a.m., and everyone was always ‘busy,’ even on a weekend. My friends’ families were made up of parents who were still together, and at least one other sibling, their time spread out and divided amongst everyone. But in our house, it was just me and Mum.

When exactly did our Sundays stop? It was hard to pinpoint. Did I really not know her ‘important phone calls’ she had to take upstairs were just another excuse to access? Instead of our usual chit chat over tea and biscuits when she came in from work, we had an awkward five minute back and forth, like we were unable to carry on a conversation any longer. I would see her eyes glaze over—however minutely—and knew she was thinking of her latest adventure, or her next one.

I tried to ignore the feeling of being pushed away that was gnawing at me. I convinced myself I was growing up as all teenagers do, distancing themselves from their parents, spending more time with friends, focusing more on school work. With Mum’s frequently alternating moods, it became easier to make all these excuses real.

When we did hang out, she talked about accessing all the time. Most of the time we talked, she was just waiting for me to stop talking so she could tell me more details of her trips. At least in these moments she was happy, eyes gleaming, cheeks flushing, her angry mood suddenly dissipated. So I let her go on.

Her credit card bills didn’t bother her anymore as she had cut back on shopping. I started to miss her pretend-guilty creep through the front door as she arrived with crinkling armfuls of bags. She stopped her bi-monthly haircuts and manicures, no longer barging into my room and pumping the ends of her hair. Now, her skin had a noticeable pallid quality to it, and she was going longer in between washing her hair.

When had she stopped taking care of her appearance?

I must have known she was going too far. But I didn’t ask where all these new memories were coming from. I didn’t call her out when I caught her eyes glazing over in their usual way, knowing she was accessing but too ashamed to tell me, just as I was too guilty to ask. We would occasionally make time to watch TV together, but as she sat in her chair, angled away from me, I could feel her living in her new world, forgetting this one, minute by minute, leaving me alone in it.

She started talking to me about things I couldn’t remember happening. It was mostly small details, like a food I didn’t like, or a day trip I couldn’t remember taking. She somehow convinced me I was misremembering. She was good at that.

When she mentioned a holiday in Scotland, however, I wouldn’t let it go. Mum had never been to Scotland. Her school had organised a small trip to Edinburgh when she was a teenager, but her parents couldn’t afford the costs, so she had stayed home, feigning illness. It had been a constant source of humiliation for Mum, so we had pledged a trip together for my 18th birthday.

You must be thinking of someone else. She shrugged it off and changed the topic.

More and more of her stories seemed curious. Knowing I couldn’t win an argument, I began testing her. I asked her about the time we headed to Bristol and Dad accidentally drove us to London. She mm-hmmed in agreement and laughed nonchalantly. Yeh, what was he like?

Except it wasn’t London, it was Wales. We had spent a very long and very wet night trying to find accommodation along dark country roads so that we could start over in the morning. I remember sinking down in the back of the car, eight years old and all too aware of the tense atmosphere as they spat words at each other, furious at the situation. They split up six months after that.

I waited for the click of realisation, or for her to tell the story again. Mum never passed up an opportunity to tell a story, even one I’d heard a million times before. She would tell it the same way every time, just like her siblings did, savouring the memory and laughing at the same points. She carried on slicing the carrots, methodically and silently.

I changed the day I spent at Dad’s and purposely didn’t tell Mum. After he picked me up from school, I sat in his car, staring at the screen of my phone, willing for her to call, to be bothered about where I was, to remember. But she didn’t. I wept silently in the bathroom when I got to Dad’s.

News reports started to appear on our screens every week, complainants of the product popping up with one weird situation after another. If Mum wasn’t accessing—which was rarely—she always turned the channel over. But when I felt her nearby absence, my thumb lingered on the remote as I listened to the strange yet familiar things that were happening to people all over the country.

What was I thinking as I watched the helpline roll across the bottom of the screen? As people wept on live TV about the loved ones they were losing? As a tear silently rolled down my own cheek? I couldn’t admit that what was happening was real, and was happening to us. I couldn’t reach for my phone and call Dad, who would have known what to do. So instead, I let my thumb grow heavy and switched channels, pushing the alarm bells out of my mind.

She had started calling in sick at work, staying at home to access instead. She’d call me as I was walking home from school to ask me to pick up a pizza; the fridge was almost always bare. I tidied around her as she accessed, trying to keep up with the accumulation of dirt and dust that had gone ignored for weeks.

What had started as small bickers became regular, full-blown fights. We would go for days without talking. I would stay with friends several nights a week, getting a stilted OK text in reply, or sometimes nothing at all, the silent complicity of our relationship falling apart.

I stopped asking which memories she was getting rid of. With our constant fighting about the accessing, I knew she wouldn’t tell me anyway. Perhaps it would have been easier to ask which ones she kept.

I understood which memories were the most valuable. Beyond the exciting ones that people like Mum chased, there were memories that a lot of people took for granted. Big milestones in life that you celebrate with your loved ones, those were in high demand. People wanted to live in moments of love, even if they were just moments, even if they were someone else’s. Like family celebrations—you always hated those big gatherings—or my first day of school—your uniform was two sizes too big, you wouldn’t even let me take a picture!—or the day I was born—it’s really not the big deal you think it is. I can barely remember it myself, I was out of it.

My birthday came and went and I didn’t have the heart to tell her. I spent the day with Dad, making the usual excuses for Mum’s absence. I wondered how many birthdays she had to have sold to forget it entirely. By then, she had started calling me by different names.

The company responsible for the product was being sued the day Mum fell down the stairs. Taking a midnight trip to the toilet, she miscalculated the layout of the house and tumbled down the staircase, lying confused and battered on the hallway floor. Had she sold such basic memories like that of her own home, or was her brain so full of new ones that it had become jumbled and dysfunctional? Nobody could tell us.

By the time a foundation had been set up, it was far too late for Mum. She had been declared unsafe to be on her own, of unsound mind, they had said. Dad moved in to take care of both of us. And now here she sits, eyes glazed over, a small puddle of saliva collecting in her clavicle, looking grey and 2D.

We let her live in her memories, no matter what they are. The product was recalled too soon for us to share our memories with her. So now I watch her day after day—her erratic wrist pulse beating in my hand, her slow-quick breathing, her flickering eyelids—and wonder where she is.

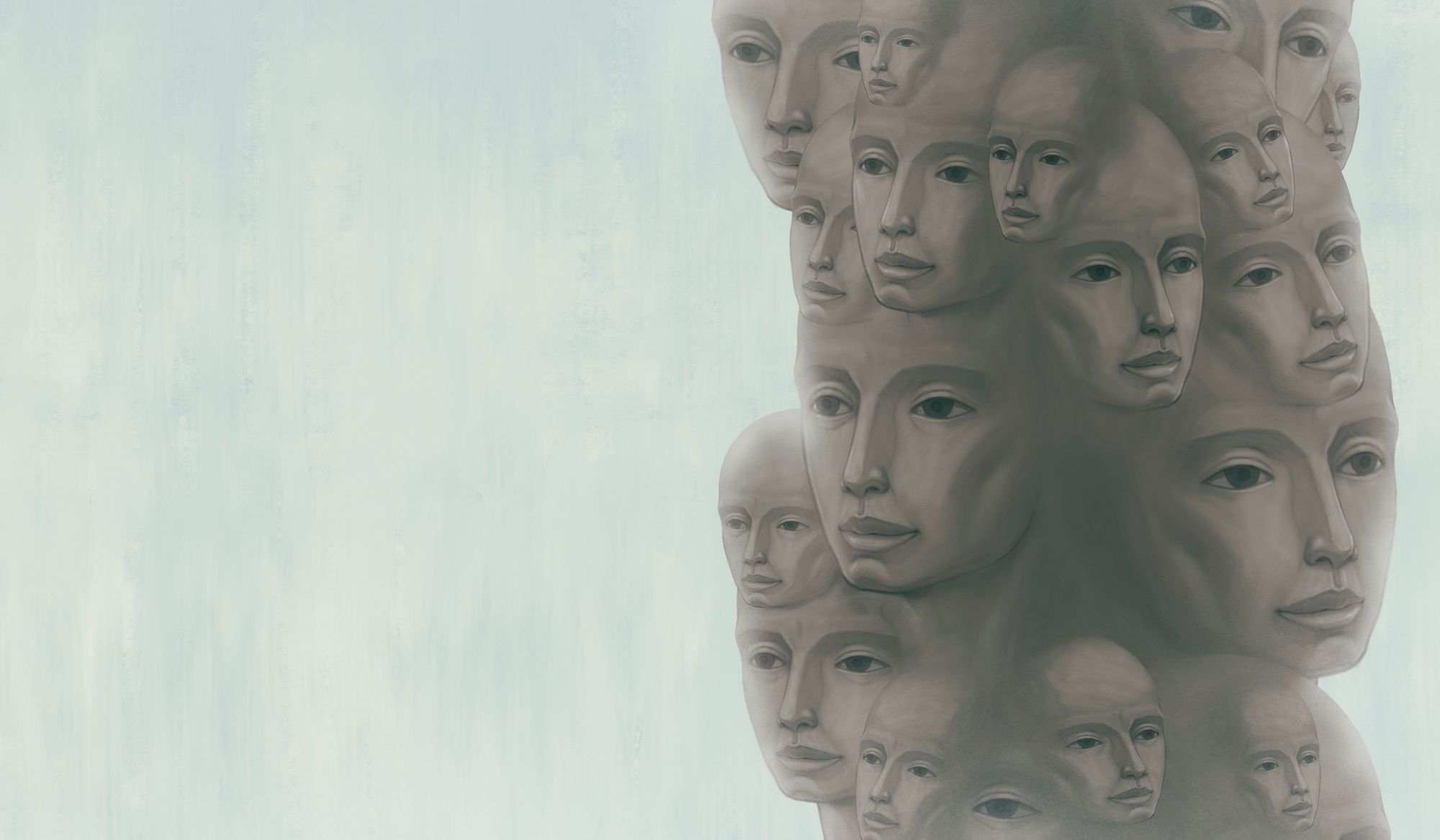

*Feature image by Jorm Sangsorn (Adobe)