Art in Politics: An Abridged History - Propaganda

This is a series that explores the historical impact of art on politics through propaganda, censorship, and freedom of expression.

Part I: Propaganda

Prop·a·gan·da (noun): information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote or publicize a particular political cause or point of view.

Toni Morrison once said that “all good art is political.” But what happens when that art goes from simply being influenced by politics to explicitly endorsing a political opinion? That, comrades, is when art becomes propaganda.

The word “propaganda” originates from the Catholic Church, referring to a committee of cardinals convened by the Pope to “propagate” Catholic beliefs amongst the population through a massive public relations campaign of commissioned scriptures, paintings, hymns, etc. However, the idea of propaganda—using art, fake news, or stories to persuade the masses to adopt a particular political ideology (or to drum up nationalism)—is as old as civilization itself.

One of the first cited instances dates back to 500 BC: the Behustian Inscription, a carved, cuneiform-inscribed stone depicting a heavily-whitewashed history of Persian Emperor Darius I and his conquest of the tribes in the area. The stone was put on prominent display for his citizens, reinforcing his rule and simply “informing” his people that he’s started all of these wars and killed all of these people for the good of Persia.

Scythians only exist to die or serve Persians, obviously.

Going off this example, an argument could be made that the concept of propaganda is actually much older. Is the Behustian Inscription so different from Ancient Egyptian depictions of Pharaohs on temple walls as Gods? Or could these pharaohs indeed control the path of the sun and help crops grow because they’re just that *special*?

If those Israelites had just quit whining and built the damn temples for their masters, perhaps their families wouldn’t have died from a famine that decade. Pay no attention to all that extra grain being traded to Kush for some nice dyes for the Pharaoh’s robes. Respect the drip, peasants.

But the most visceral example of artistic propaganda—this idea of demonizing ‘the other’ by stereotyping and dehumanizing them through offensive media depictions in order to gain support for a war or colonization effort—is much more widespread. Roman propaganda literally invented the word “barbarian” (which we still use in the same context to this day) to dehumanize the Germanic tribes they conquered in order to promote the idea of “civilized” Roman rule among the population. After all, many of them had been conquered by Rome in previous wars and would thus need sufficient “re-educating.”

During the Renaissance and the dawn of industrialization, The English—whose empire was modeled after their Roman forebears—employed the same strategy with the term “savages” to justify colonial expansion. The term was spread widely in newspapers and magazines, but it was classic literature (The Jungle Book, Heart of Darkness) that cemented the idea that Britons were inherently more “civilized” than their non-British counterparts.

One former English colony—the USA—even went so far as to appropriate the “savage” terminology for their “Manifest Destiny” campaign against First Nations people. Political cartoons in newspapers, posters up in establishments across the west, and even early radio programs like “The Lone Ranger” helped to ease citizens into the idea that the open frontier was free land for the taking, rather than what it actually was—an invasion by an occupying force of sovereign land. Once indigenous populations were sufficiently defeated, the United States promptly revised and whitewashed the brutal history of this genocide through folksy 20th-century Western films (Little Big Man, Two Rode Together, Hombre, The Last of the Mohicans (1920), Dances With Wolves). Because fun little gunfights on horseback are much easier to stomach than native children being forced into “re-education” schools, having their hair cut off, and stripped of all semblance of their culture.

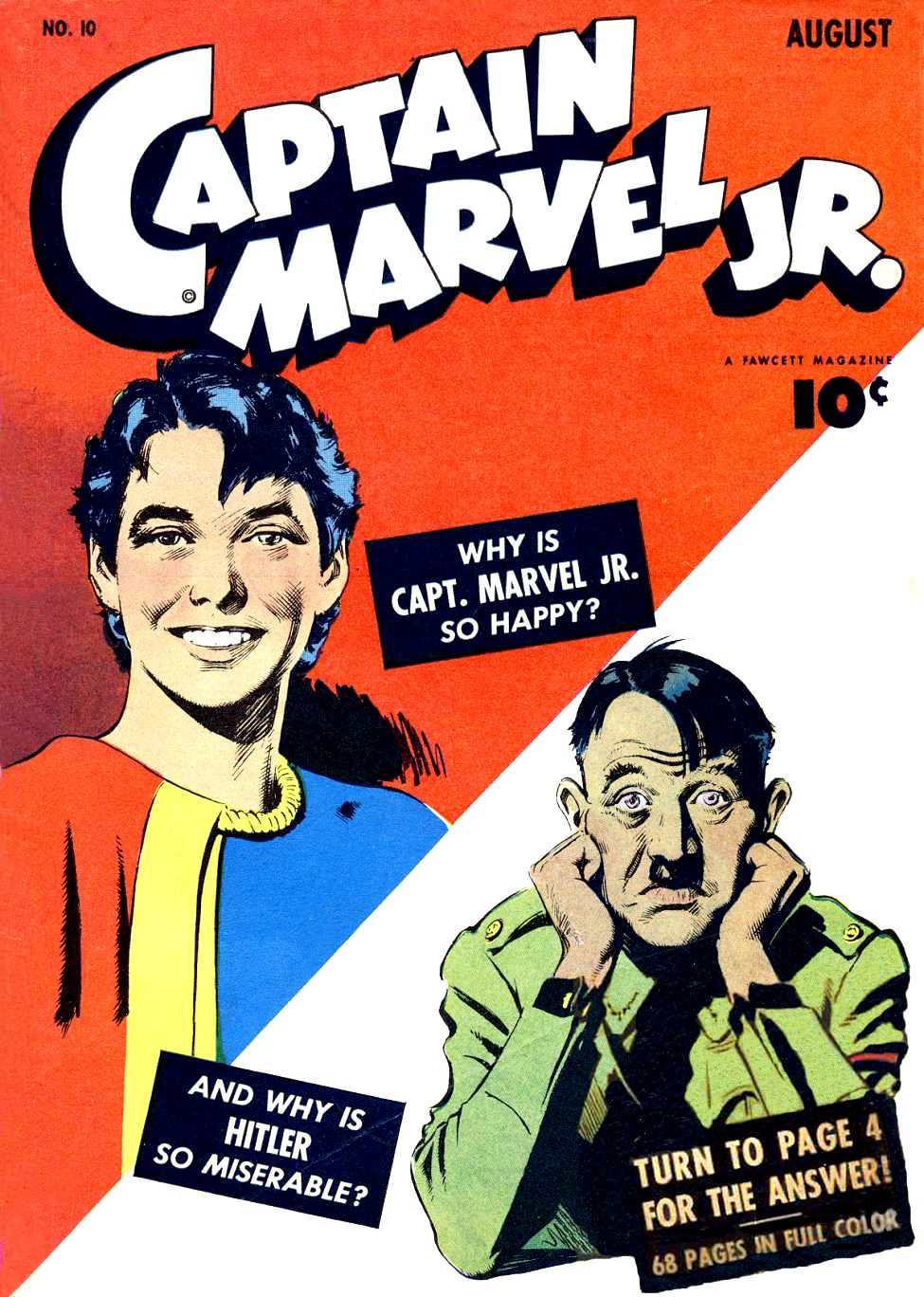

This trend of propaganda being used to further authoritarian conflict has continued throughout the ages. From the Soviet space program posters from the 1950s to kick off the Cold War, to the classic Uncle Sam “We Want You” American recruitment poster, to Leni Reifenstahl’s seminal films that played a central role in shaping the Nazi propaganda machine.

However, propaganda is not exclusive to fascism or authoritarianism by any stretch. It transcends political ideology. If you’re a youngin', and currently live in the United States, you might even be thinking of the bombardment of political memes—either far leftist or alt-right—depending on how the algorithm perceives your political position.

“But wait,” you say, “Memes aren’t commissioned by the government! Neither were all those Western movies! People came up with them all on their own. How could they be propaganda?”

This comes from a common misconception that propaganda MUST be directly commissioned or created by a sitting government in order to be classified as propaganda. Although, incidentally, a not-insignificant amount of the memes you’ve seen (on both sides of the spectrum) actually were commissioned by a government: the Russian government. But that’s just fake news, right?

In reality, there are only two required qualifications to be considered propaganda: that the art explicitly advocates for a political stance, and that it uses misleading, false, or biased depictions to do it.

Take the United States’ surge of post-9/11 ooh-rah military movies: Blackhawk Down, The Hurt Locker, and Restrepo, to name a few. Unlike Reifenstahl’s films for the Nazis, the U.S. military did not commission these films, and they did not require government approval to show in theaters. However, the military did give each of these films direct financial assistance and donated plenty of tanks, guns, explosives, and other equipment for use as props—vital competitive advantages that films more critical of the military might not have, or might need to pay more for.

As an added benefit—or perhaps, as intended—the films boosted military recruitment during the worst years of the Iraq and Afghan wars.

Even without that help, the narratives of strapping American soldiers fighting almost-demonic stereotypical portrayals of Muslim “terrorists” belie the political stance that these films advance: the United States military is an absolute force for good in the world, and that the people in these countries are all rabid terrorists that need to be stopped at any cost.

While propaganda can be an effective tool to warp the viewer’s political opinions through art, it’s nothing without the secondary ideological weapon that often accompanies it: censorship.

*Feature image: Cover of Captain Marvel Jr number 10, as published by Fawcett (August 1943). Note: This image has lapsed into the public domain, due to Fawcett failing to renew the copyright.