Hamlet, Mad Men, and Universals in Storytelling: An Interview with Robert McKee – Part I

From the L.A. Screenwriter collection.

Robert McKee has become synonymous with the word “story.” He is the most sought after screenwriting lecturer in the world. A Fulbright scholar, his students have included over 60 Academy Award winners, 200 Academy Award nominees, and hundreds of Emmy and DGA winners. Peter Jackson has referred to him as “The Guru of Gurus.” And, of course, Brian Cox’s portrayal of him in the Oscar-nominated film, Adaptation, has become legendary.

In this two-part interview, I discuss story’s past, present, and future with the man who literally wrote the book on the subject—Robert McKee.

John Bucher (JB): I’m often reminded of a quote from Flannery O’Connor, who said that everyone knows what a story is until they sit down to write one. What makes a good story? Is there such a thing as a bad story?

Robert McKee (RM): Well, of course there is, and we suffer through thousands every year, but the answer to the question “what makes a good story” really depends on point of view. My definition of a good story, from the audience’s point of view, is very simple. It hooks, holds and pays off.

It hooks their interest, emotionally and intellectually, and it holds their interest, and deepens their involvement emotionally, and increases their curiosity intellectually, and then finally it pays off an experience that satisfies their expectations for both the head and the heart. It hooks. It holds. It pays off.

JB: What would you say is universal in storytelling? Obviously you give your talks all over the world and the things you have to say connect with people from every country in the world. So, what is universal in storytelling and what is specific to cultures?

RM: Well, let’s begin with what’s universal. There’s a whole set of fundamentals, like curiosity. You have to take an audience through time such that they are unaware of the passage of time. An hour, two, three hours go by and suddenly they’re looking at their watch saying, “My god, it’s over.” You have to engage their curiosity so that they’re constantly looking ahead and do not notice the passage of time. That is a universal.

There must also be, at some level, conflict. It may or may not be surface. It may be inner-conflict. It may be very subdued and suppressed. It may be very overt. It may be on any level of life: physical, social, personal, inner, even subconscious. But somehow within the story, the struggle to achieve whatever it is the character needs is met with antagonism. They can’t get what they want the easy way.

There must be a value at stake, at least one. It could be very complex. It could be many values, but there has to be a core value that is the essential subject matter of the story: justice, injustice, a meaningful life versus a meaningless life, love and hate, aloneness versus togetherness, immaturity, maturity, a lacking of humanity, a gaining of humanity, and so forth. There has to be a value, and values come in as a binary, positive and negative.

The movement of a story everywhere in the world, universally, is a dynamic movement from positive to negative in terms of whatever value is at stake, building positive/negative, positive/negative and progressing in terms of the jeopardy or the risk that’s at stake in the character’s lives. And often where differences lie in terms of culture is in this issue of values.

For example, I lecture often in China, and Chinese culture is founded on respect for authority, and indeed even further than that, obedience to authority. The father figure and the mother figure, but particularly the father figure dominates culture and characters. Politicians, teachers and so forth … people in authority are looked up to and respected outwardly, at least in terms of behavior.

In America, you remember back in the 60s or 70s, there were bumper stickers that said, “Question Authority.” Here, we value independence. We value rebellion against authority because in our culture, authority has a negative connotation. And in politics today, all our complaints about the inequities in the economy, accusations of the rich abusing their money to pull strings is a rebellion against authority. So, if you make a film about rebellion against authority in the United States, it may have great success. If you make that same film in China, the censors may not even allow it to be shown.

So, there are great differences from culture to culture in terms of the perception of values. Some cultures, for example, are very romantic. Love—romantic love—has got tremendous value. I read a study some time ago when I was preparing my Love Story lecture, where they went around the world asking this question: “Are you, at the moment, in love?” They discovered that the most romantic culture in the world is Russian. 75% of all people in Russia believe that they are currently in love. The least romantic culture tended to be Arabic or Islamic cultures, where less than 50% believed that they were currently in love.

Our notion of romantic love in America is somewhere around 60%. And so our notion of romantic love is not the same as the Russians. It’s not the same as the Egyptians. They all have romantic love, but the degree to which they idolize it varies. Once you understand the core value at the heart of the story and once the audience can experience or understand that value, then the dynamic is universal. This is why we can enjoy foreign films—films from very different cultures—so long as the filmmaker makes us understand what’s at stake.

Another universal is empathy. You could have great curiosity and that might hold you through the story, but there’s no suspense. Curiosity is not the same thing as suspense. Suspense is emotional curiosity. And so when the audience empathizes with the protagonist, recognizes shared humanity, they say, “She is a human being just like me.” When they then invest in the the core character and want that character to have whatever the character wants, then they’re emotionally involved, and then you have tremendous suspense.

These things are true in every culture. How exactly those things get used is different. Take time for example. In Japanese culture they have an enormously powerful patience, and they will accept a much more static story than we Americans will. And you could reach a certain point in the story in Japan where the characters are in some sort of crisis, and just cut to an image of Mount Fuji, and leave that snow-capped mountain on the screen for two or three minutes, and the Japanese will sit there thinking about the problem the characters are facing, as they look at this image. Americans say, “Why are we cutting to the mountain?”

JB: Can you speak a little bit about the structural relationship between the protagonist and the antagonist?

RM: Well, structurally, the protagonist is one person—man, woman, or child—at the heart of the story, but it could be co-protagonists, like Thelma and Louise. You could have a trio, like The Witches of Eastwick. You could have The Dirty Dozen. The size of the protagonist, the numbers of people involved varies from story to story, but when they all want the same thing, they’re all struggling toward that desire and they suffer and benefit mutually, they’re still just “the protagonist,” no matter how many there are.

So, protagonist varies in that way. The same thing can be said about an antagonist. It could be, you know, multiple antagonists in an action film. You have archvillians, you have all their goons, and assassins and femme fatales and the societies to be rescued and armies to be defeated, and so the size of an antagonist striking, again may be massive.

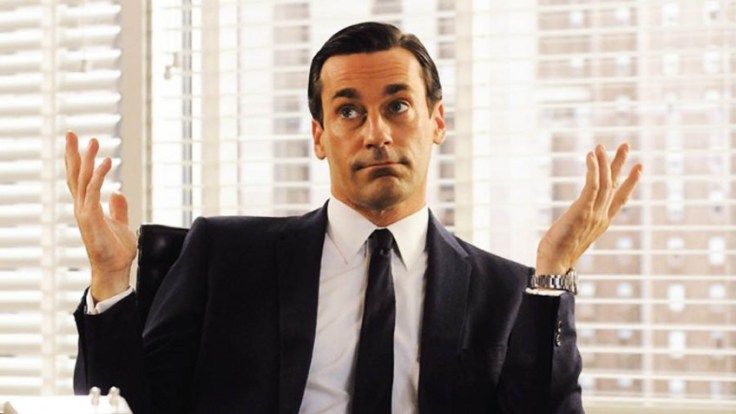

On the other hand, the protagonist can be his own worst enemy. Take for example that marvelous television series, Mad Men. Don Draper has any number of antagonists through his career—his marriages and so forth, people who are opposed to what he wants, but he is the antagonist. His damaged childhood, his experience in Korea, and his attempt to lead somebody else’s life that has been eating away at him decade after decade, driving him into alcoholism and all the rest. He is the protagonist and antagonist of the story. And so structurally, the protagonist is one side we empathize with. The other side (antagonist) we don’t.

In horror films you have victim protagonist and monster antagonist, but in many horror films, we get on the monster’s side, and we actually identify with the monster to a point because we love their power, and power’s a very attractive thing. We would really love to have the power of a monster at times. Just to settle scores. So you can’t even say that the structure is that we always empathize with the protagonist and we’re always opposed to the antagonist. It’s not always the case. In certain stories we get on both sides. Sometimes the audience is switching sides back and forth, back and forth.

In certain stories the antagonist is ubiquitous. With Samuel Beckett, the antagonist is time. Living in time and knowing that it’s going to run out. So the antagonist doesn’t even have a personality. It’s just a condition of life and bringing about what we used to call the existential crisis. I mean a protagonist is simply the character whose life has gone out of bounds and they are struggling down the spine of action to restore the balance of life. All stories are essentially that. A protagonist’s struggle to put life back on an even keel, somehow to restore the balance.

I know what people want. What your readers want is an easy, clear, concrete, straightforward statement of, “Do this, and you will be successful. Don’t do this, because you won’t be successful.” But, John, I’m going to give you answers that take in the whole of storytelling.

Part of my teaching is just to make it clear to people that when you ask a question like, “What’s a protagonist? What’s an antagonist?” there’s no single answer to that question. And, therefore, you’re going to have to use your imagination and think it through. There’s no formula. There’s just form.

JB: What you’re saying definitely feels more true than any formula anyone could approach. I’m definitely with you.

RM: That’s good. I hope you can convince your readers of that, too, because in the panic to achieve, to try to make a living doing this, often people will resort to the most simplistic cliché answers to these questions, and just copy. They copy what other people do, thinking, “Well, this is what made them successful, and I can do some little variation off of this and it will make me successful.”

But the great writers only concentrate on the relationship between them and their audience and they want to express their knowledge of life uniquely. They don’t have to resort to difference for the sake of difference, and a lot of bad filmmakers do. Look at long-form television. We’re witnessing some of the greatest writing ever in America. And these people who are writing these great series are not looking over their shoulder. They are out there exploring and doing things. A hundred hours of drama, doing things that no one has ever attempted before … The complexity of character in these great long-form series is infinitely greater than anything that was ever done in film, ever.

I do a TV day, a whole day study of what makes a great TV series, and the key is character, and complexity of character. Because, people will follow a TV series as long as the central character is changing, evolving in some way, or being revealed. I mean, there’s secrets or there’s aspects of this character that have been there since the beginning of the series and they are now being dramatized and brought out. So the character’s either being revealed for who they’ve always been, but we didn’t know, or they’re evolving into a character we didn’t know, but one way or another through revelation or change, the character is not staying the same. Once that character’s exhausted, they cannot change, there’s nothing left to reveal in them, the series is over.

I mean, this is what happened with Dexter, for example. Two or three seasons before the end of the run, Dexter was exhausted, and we just ran out of interest. On the other hand, in Breaking Bad, Walter White was still being revealed until the very last scene. We always suspected he cared for Jessie, but when he throws himself between Jessie and the bullets, he’s still being revealed.

In film, we talk about the three-dimensional character, which is a cliché. Usually characters are more dimensional than that, at least central characters are, but three is a sort of standard. I did a study of Tony Soprano as a 12-dimensional character, and I did a study of Walter White as a 16-dimensional character. They have eighty, a hundred hours of storytelling, and what brings out dimensions primarily is the relationship between characters.

Hamlet used to be thought of as the most complex character ever written, and maybe he was, or is, through his time in the theatre, but he only has four hours. And he only has relationships with six or eight other people, and so in that four hours and in those relationships, his complexities are all revealed and he changes. But, that’s only four hours and six people.

*Feature Image: John Hamm in Mad Men / AMC