Leaps and Bounds: Writer Ariel Levine Makes Her Ascent on Better Call Saul

Sports and writing share no similarities in action. Their crossover is in practice. Long hours, a clear sense of discipline. “Commitment” and “sacrifice.” Writer Ariel Levine once had Olympic gold and a career as a ballerina in her sights, then discovered the glory of television. Now she’s writing for one of the most celebrated TV dramas in history. Still learning, still practicing, and still proactive in the pursuit.

Ariel Levine had a plan. Now she had to execute.

She’d been working her way through the assistant ranks of the "Breaking Bad"-verse for nearly a decade: post-production assistant on the final season of "Breaking Bad"; post-production assistant on season one of "Better Call Saul"; writers’ PA for season two; writers’ assistant for seasons three through five. Writing the finale for the critically-praised fifth season (which aired April 20th on AMC) with "Saul" co-creator Peter Gould. Not to mention the Emmy she’d won for writing a collection of shorts tied to the show.

Yet here she was, about to make the biggest pitch of her life: requesting a promotion to staff writer on the sixth and final season of a show some call the best on television.

She was done with assistant roles.

Pitching is a given for television writers. So, too, is planning for conceivable obstacles your characters can face in any given episode—skills that were especially valuable for Levine in this moment. Leading up to her meeting with Gould, she envisioned every possible point and counterpoint that could come up that day. She imagined a dozen conversations, a hundred scenarios. Levine tried to have answers for everything.

“I had a whole speech, I wanted to finish out the show,” Levine said.

“But,” she added, “I was ready to be a writer.”

All throughlines came back to one, inescapable point. She wanted to write for television, and this was the moment to make it happen.

When the time came to meet, Levine sat down in front of Gould, took a breath, and leaped in.

Anyone who’s gone for a staffing gig in Hollywood—or taken a general meeting—knows selling yourself is key.

Oftentimes, the industry speaks of identifying your “story” and pitching it succinctly. Have key anecdotes ready at a moment’s notice, they say. Questions can range. What incident in your life makes you uniquely qualified for writing this particular thing? What gap do you fill in a writers room? When did you know you wanted to write for television?

The answer to the last question might seem especially surprising when it comes to Levine. Growing up in Dallas, Texas, Levine hardly watched dramatic, narrative television. She readily admits she didn’t consider TV writing a possible career until entering college. Her parents: firmly in the TV-rots-your-brain camp (except for sports), and instead, were keen to see their daughter reading a book or playing outside.

Over two weeks in 1996, she recalls watching the Summer Olympics in Atlanta. The year when the United States women’s gymnastics team would become the first in American history to win gold in the team competition, and the now-iconic moment of Kerri Strug sticking the landing on one foot. Levine watched, entranced, specifically with Strug and Shannon Miller, two members of a squad that would later be crowned as “The Magnificent Seven.”

“I thought to myself, ‘I want to be that. I want to do that,’” Levine said.

“I spent all my time doing competitive gymnastics for years. I was convinced I wanted to go to the Olympics.”

An eventual injury sidelined her for months—an eternity for gymnasts—and once she recovered, she transitioned to ballet. Many of her skills transferred. Her middle and high school years were routine: private lessons in the morning, rehearsal in the evenings. For her, it was the ballerina life or bust.

“If you’re going to pursue that as your career, you have to know that that’s the only thing you ever want to do. It’s such a commitment and a sacrifice,” she said.

But the injury bug bit once more. She broke her foot and sprained her ankle at the same time, something she describes as the single most painful moment in her life. Also painful: rehab. Stretching her foot and ankle as the bone healed proved draining. She began to think ballet wasn’t her only option.

She would later apply to college and begin her freshman year some 1,700 miles away from her home in Texas.

Depending on who you ask, the timeline for the Golden Age of Television is, at best, nebulous.

Does it begin in 2002, with the debut of "The Wire" and "The Shield"? Is it a few years earlier, when "The Sopranos" became synonymous with mobsters? "Mad Men" and "Breaking Bad" introduced the world to AMC as a dramatic powerhouse in 2007 and 2008, respectively. Are they the arbiters of “Peak TV?”

Entering Boston University, Levine had no reference point when it came to any of these shows, but she would spend the next few years rectifying that. Her roommate, shocked at the lack of television in Levine’s life, threw everything she could at her. Comedies, dramas, prestige content. Levine binged all of "Lost" in preparation for its series finale.

“It was kind of this deluge of TV all at once. A lot of 'The Office' and 'Friends' and 'Six Feet Under,'” Levine said.

“And I sort of realized, wow, I really enjoy this. This is great!”

Amidst the glut of TV, and missing the creative expression of her ballet performances, Levine started pursuing other artistic outlets. She auditioned for an a capella group, but it went nowhere. Dance was out of the question, as the thought of returning after stepping away was too painful. She finally settled on acting. And it so happened that Boston University was home to "Bay State," the longest running college soap opera in the country.

Levine signed up to read for the role of a character named Alexis. It was a dark scene involving a suicide attempt, and she practiced with her roommate before going in for the audition. She arrived at the show’s studio and stood in front of a table of four or five people, including producers and writers, and performed the scene.

It didn’t go well. Perhaps because she employed the same method to act out her suicide attempt she’d used when practicing with her roommate.

“She didn’t warn me against using finger guns, which I definitely did when practicing!” Levine said, adding that when she checked the cast list later, “I noticed I was not on that list ... And I was like, ‘Yeah, that tracks.’”

One good thing she took from the audition was how it felt to be on set, and onstage, with creators who seemed like genuinely creative people. These were artists she would love working with. The following semester, Levine joined the crew of "Bay State" as a production assistant, doing a little of everything. She shadowed directors and producers, sat in on the editing process, operated the cameras, set up sound equipment (“holding a boom mic during long scenes is a great upper body workout”) ... But what fascinated her the most was the writers. She wanted to do what they did.

“I realized what I loved most about TV was the story. I wanted to help decide what happens to the story, what happens to the characters,” Levine said.

“The thing with TV versus film, or any other medium, is that you can start with this set of interesting characters and watch them grow and change and evolve over an extended period of time.”

The next semester, Levine applied to join the writing staff. The process sounded simple. She would be given a list of characters, and she’d have to write a spec scene, showing she understood the voice of "Bay State." Simple. Except Levine had never written a script before. She’d only started taking screenwriting classes that semester.

And so one weekend, she spent about 48 hours writing 30 (... 30) drafts of a spec scene using the most humble of all screenwriting software: Microsoft Word. She wrote, edited, rewrote, re-edited. Levine admits she’s a slow writer in general, but part of what made the process difficult for her was the feeling that she was working in a vacuum. She’d only worked on the show for a semester, a total of three episodes, and she’d only seen six episodes altogether. She fixated on getting the voices and characters of the show right, when she didn’t have a full grasp on either.

She finished. Turned it in. And waited.

“It’s hard, because you want it to be perfect, but it’s art, so it’s never going to be perfect,” Levine said.

Two weeks later, she heard back. She’d gotten in. What followed was a feeling she can only describe as pure ecstasy—the validation that comes with positive reinforcement, and the excitement that comes with the opportunity to grow, learn, and develop. She dove right in, and it couldn’t have come at a better time. While getting the practical application that came with writing for "Bay State," Levine was settling into the more advanced theoretical screenwriting courses encompassing her major (which, surprisingly, she’d only officially declared the semester before). She was learning and doing simultaneously.

When she looks back on that experience, her first foray into creating scenes for actors to perform, she can’t help but do so with fondness. The writers would get together in someone’s dorm room, 5 or 6 total, and break story, craft scenes, assign characters. Each semester, they got to introduce new characters and situations. Levine grew as a writer, learning her own process and becoming familiar with what worked and what didn’t for her as an artist.

“It was a blast. You get to do the thing you love for real. You’re not just sitting, watching. You’re participating,” she said.

“There is something to be said about working with a group of writers, seeing it all come together, getting and giving notes, sitting around editing. This was a really unique experience to see it all and to get your hands dirty.”

She would write for "Bay State" for three semesters. On track to graduate a semester early, Levine left the show at the end of her junior year and wrapped up her Boston University studies on a satellite campus. But she wouldn’t be studying anywhere.

Her final semester would be spent on the opposite coast.

After growing up in Texas and going to school in Boston, how does Levine describe her first exposure to living in Los Angeles?

“A little bit of a culture shock,” she says, laughing.

“Learning how to drive around Hollywood, what it’s actually like here. I was still kind of figuring things out.”

During that last semester, Levine finished her degree by tackling a workload which included two internships. One in development at Bravo, the other in the film music department at Universal. She graduated, and two months later, she took a job that she found on a BU alumni board, in reality casting with MysticArt Pictures.

Casting reality TV can be an arduous process. There’s outreach, interviewing, re-interviewing, then condensing a potential cast member’s story into a one-page document. Every show looks for different people who fit into varying categories, oftentimes tied directly to the program’s premise. From March to November, Levine cast three different shows: "The Moment," "Wipeout," and "I’m a Teenage Bride." The first two seemed fairly standard. As for the third:

“[Bride] was an interesting one to do outreach for. We’d have to find places to advertise, where we might attract, you know ... teenagers who were getting married,” Levine said.

“We went to bridal shows just looking for young people. It was insane. Very outside my comfort zone.”

After months of reality TV, Levine had enough. Her heart was in scripted television.

She’d kept in touch with one of her mentors, Jenn Carroll, the head writer of "Bay State" during Levine’s first semester, and Carroll knew Levine was unhappy in reality TV. Carroll was on the west coast now, too, and she had an opportunity for Levine: interviewing for a post-PA position on the final season of "Breaking Bad." She reached out, and Levine took the interview.

She didn’t get the job. She’d made a good impression, but let them know she wanted to get into writing. They preferred someone whose future was in post, so they went with another hire. Levine remained in reality TV, continuing to work on "Wipeout." A month later, casting wrapped, and MysticArt offered Levine an opportunity to stay on with them for another show. She called Carroll seeking advice, and Carroll had more to offer than guidance.

Fortuitously, a temporary spot on "Breaking Bad" had opened up, and because she’d been vetted for the previous position, she could have it if she wanted it. Now, the once ballerina-to-be who a few years prior had never seen an episode of ""Breaking Bad was working on the show’s explosive final season.

“It was the opportunity of a lifetime,” Levine said.

“I would say if there was ever a pivotal moment for me, it was that. Being there at probably their craziest time. They were breaking the last episode of the series, and I’m running around not knowing what’s going on!”

It ended up being a stressful, intense, but educational two-and-a-half weeks. She says she was basically a writers’ PA—doing runs and answering calls—and while everyone was great to work with, she couldn’t help but feel self-conscious. Levine likes to know she’s doing something right, and doing it well. When she’s learning something new, she wants to learn it quickly and do it the best she possibly can, but here, in the throngs of a production that was at its peak and had been going strong for years, it was easy to feel overwhelmed.

“It was just a well-oiled machine at that point, and they needed someone who could jump in and go, and it was stressful for me,” Levine said.

“But they were insanely nice and amazing, all of them. These are the most talented people in the industry, and it was so much fun to work on a show that I was a fan of, something I obviously didn’t get to do working in reality.”

Another thing she didn’t get to do while working in reality: interact with "Breaking Bad" creator Vince Gilligan. Specifically, interact with Vince Gilligan in a way she describes as “hilariously embarrassing.” One week, Levine was about to make a run when she realized her car wouldn’t start. In addition to analyzing every part of her job to make sure she was doing it to the best of her ability, she had to get her car started. She was telling Carroll the situation, when out of nowhere:

“Vince comes out and says, ‘Do you need me to jump your car for you? I have cables.’ I almost cried,” Levine said.

“I was like, oh my God, Vince just offered to help jump my car, and all I could think was, ‘No, it’s OK! You go back to the writers’ room, the temp will handle it. Thank you for offering!’”

She ended up calling AAA, her car was resuscitated, and she finished up her temp job with high marks. Levine spent the next several months being a post-PA on an assortment of shows, including "Twisted" on ABC Family (now Freeform). Eventually, she got onto a post-production team working on the show "Enlisted," the same post team from "Breaking Bad."

Then came the news. Gilligan and the "Breaking Bad" team were creating a prequel—a risky and unenviable move—following up what some considered to be the best dramatic show of all-time.

A month before the debut of "Better Call Saul," Variety, on the cover of its January 2015 issue, distilled the show’s goal down to one crucial thing: “Escape Breaking Bad’s shadow.”

Indeed, "Saul"—Vince Gilligan and Peter Gould’s prequel series examining lawyer Jimmy McGill’s descent into Albuquerque’s "Breaking Bad"-verse—faced a barrage of questions from critics and fans alike. Did we really need more to a story already hailed as perfect? What more could be added? Most importantly, could you craft an entire series from a character who was known more for his comedic relief? Spin-offs were notoriously tricky to execute, and Gilligan himself had already been part of a short-lived one. After writing for "The X-Files" in the 90s, he’d branched off to co-create and write episodes of its spinoff, "The Lone Gunmen." It only lasted 13 episodes. As Variety pointed out in their piece, “For every 'Frasier,' there’s a 'Joey' and an 'AfterMASH.'” (For what it’s worth, five years later, all 'Saul' has accomplished is more than 30 Emmy nominations, including Best Dramatic Series noms four years running ...)

None of the above mattered to Levine, whose priorities were focused elsewhere. She had a decision to make. Should she work on "Saul" as, yet again, a post-PA? Conventional wisdom said that might not get her any closer to her ultimate goal.

“I was a little torn at the beginning. I wanted this chance to be in the Vince Gilligan universe once again, but I also knew I wanted to make the transition to working in a writers’ room,” she said.

“What really kind of clinched it for me was when I found out the post-team was going to be in the same office as the writers. At that point, I knew I was going to have exposure to the writers, get to know them, help out, and it made the transition a little easier.”

As a post-PA on "Saul," Levine did everything from getting lunches to handling and watching dailies. She always made herself available, chipping in to do whatever she could, whenever she could. Levine especially enjoyed the editorial process, because it meant sitting in the editing suite and watching Gilligan and Gould work.

“That was just unreal,” Levine said.

“You can’t really be a writer without understanding what happens in the other arms of production. What happens on set, what happens in post, it’s such a great opportunity and it’s such useful information.”

With work on season one winding down, word got out that a writers’ PA position was opening up. Levine asked to be considered, and just like that, she was one step closer to the people she hoped to emulate. Her duties in season two included writing casting sides, which she would do by adapting a scene from the script, changing names and locations to avoid spoilers. Research was also a priority, and for a show that actually took place nearly two decades in the past, that ended up being vital. How was a particular thing done in New Mexico? How was it done in Albuquerque? How was it done in Albuquerque in 2003?

Levine became fluent in legalese, from knowing the different types of pre-trial hearings to the authenticity of circa-2003 legal documents. She took the initiative of getting a membership to the Los Angeles Law Library, a crucial resource in her endless quest for research.

“What I love about the fans of "Breaking Bad" and "Better Call Saul" is they’re so detail oriented,” Levine said.

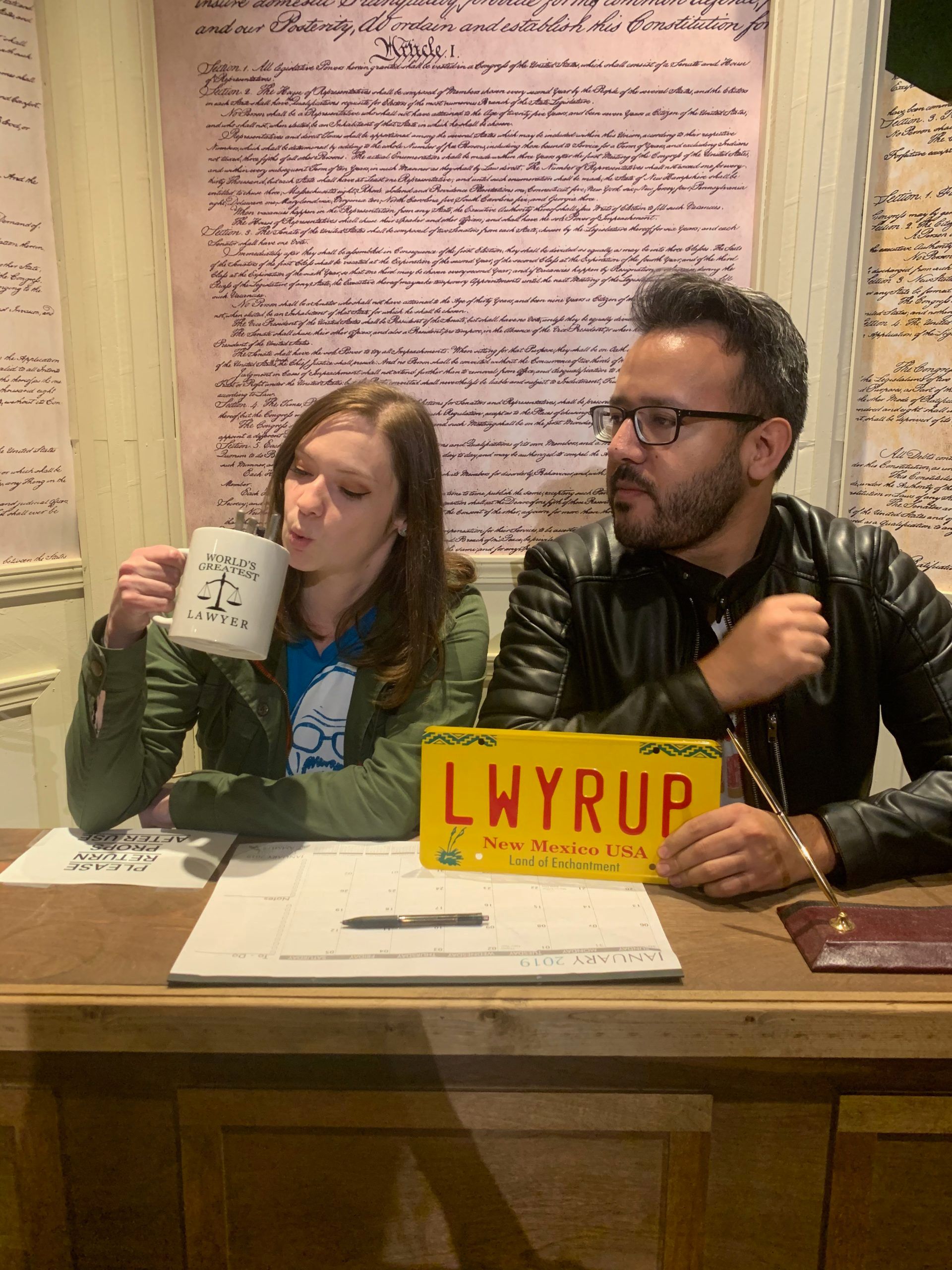

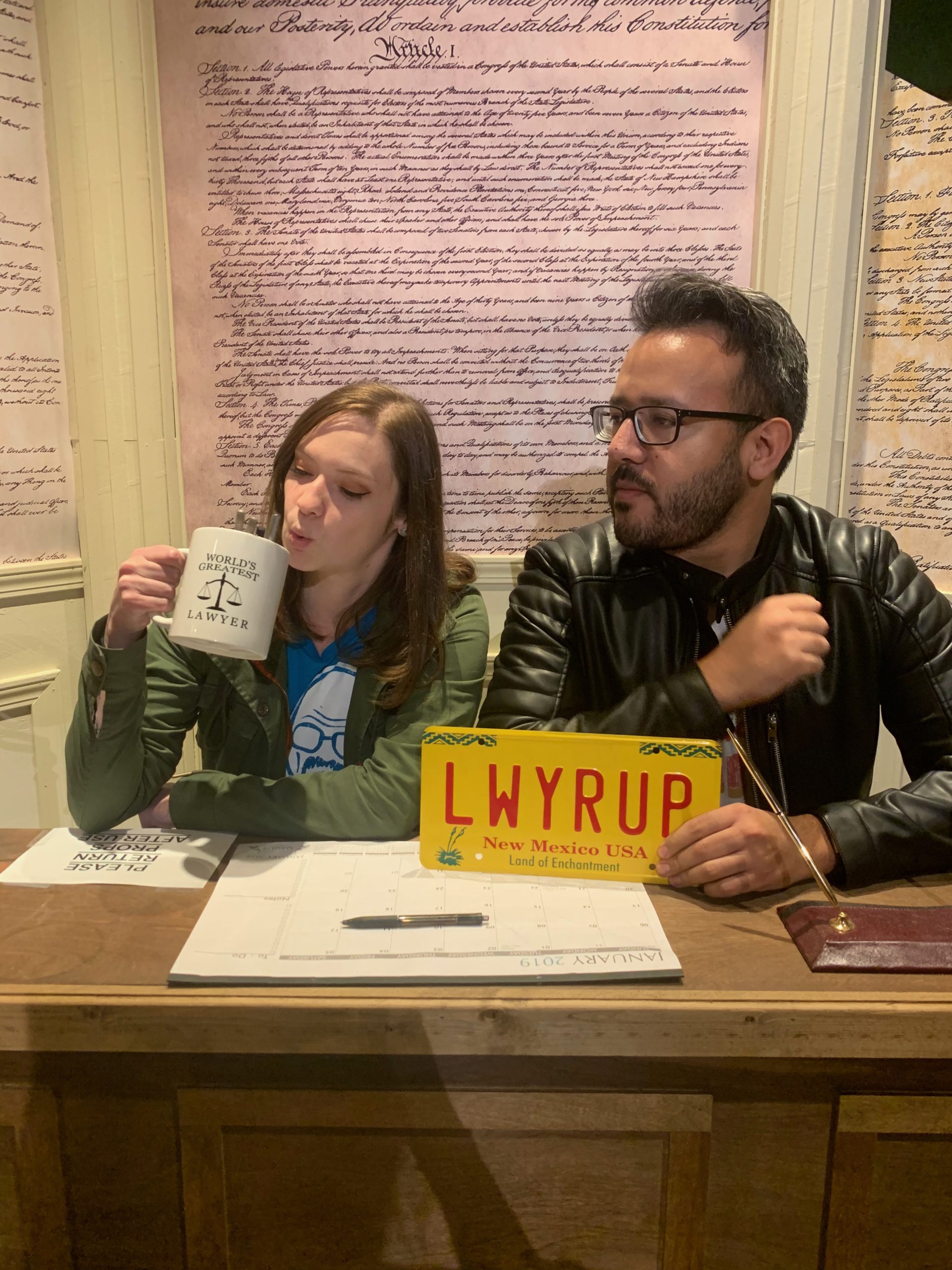

“And we’re now in a world of 4K, where you can pause and zoom in and see everything. Every piece of paper and every legal document is a real document that has been drafted by the writers’ office in collaboration with our fabulous props team—they do so much work, and we are unbelievably grateful for their patience, ingenuity, and attention to detail! They deserve all the ... props. I was more than happy to take on as much of that as I possibly could.”

Season two came and went. For season three, the writers’ assistant was promoted to staff writer, and Levine bumped up from writers’ PA. As the new writers’ assistant, she’d get to spend the majority of her day in the writers’ room, paying off her gambit to continue doing post-PA work back in season one. It was a role she’d carry for the next three seasons. Levine would track the pitches that landed in the room—and occasionally, got to pitch.

But the majority of her responsibilities lay in maintaining and referencing a database of the established world of "Better Call Saul," and, if it applied, "Breaking Bad." How did Jimmy take his coffee? What were Kim Wexler’s habits, likes and dislikes? Had Mike Ehrmantraut mentioned a past moment in "Bad" that would come to pass in "Saul"?

As she grew into her role, Levine began working with the AMC Digital team to write “training video” digital web shorts meant to accompany the show. During season three, she wrote the ten-part series, "Los Pollos Hermanos Employee Training," featuring Giancarlo Esposito. Each short, running around two minutes, combines tips from Fring, animation, and Easter eggs from the show to witty effect. The Academy of Television Arts & Sciences certainly thought so: Levine won an Emmy for Outstanding Short Form Comedy or Drama Series at the Creative Arts Emmy Awards in 2017.

“Even getting nominated didn’t feel real, and then when we won, it was a mass amount of excitement mixed with a lot of impostor’s syndrome,” Levine said.

“Like, ‘Oh my God, how did this happen? What is this thing that’s sitting in my office now?”

When season four wrapped, Levine inquired about a staffing position for season five, but "Saul" had a full room. Gould made it known, though, that he wanted Levine to co-write an episode. If that went well, they’d revisit the topic at the end of the season. Sure enough, halfway through writing season five, Levine found out she’d be co-writing an episode with Gould himself.

But she wouldn’t be co-writing any episode: they were tackling the season finale.

While credits oftentimes name one or two writers for episodic television, the process is usually far more all-encompassing.

Rooms take months breaking season arcs and individual episodes. Episodes are then doled out to assigned writers, who then receive notes from everyone from the showrunner to network execs.

When the time came for Levine and Gould to break and co-write episode 5×10 of "Saul"—later given the ominous title “Something Unforgivable”—the two parsed out how best to divide the script, and then got to work. Gould gave Levine notes on what she wrote, and then asked for Levine’s feedback on what he’d written (“That was wild, because he’s brilliant!”). It was an entirely new experience for Levine, who was used to being in the writers’ room not as a writer, but as an assistant.

“As the writers’ assistant, your brain is kind of bifurcated. You’re focusing on the notes, the research, making sure everything is where it needs to be. The other half of your brain is just trying to be creative,” Levine said.

“Being able to put all your energy toward thinking about story was new to me in this setting, and Peter is such a great teacher and collaborator. It really felt like we both had a hand in creating the script together. It was wild. It was so much fun.”

Co-writing the episode also ensured Levine would be on set during the episode’s 14-day shoot in Albuquerque. While she had been on the set of "Saul" previously as a fill-in during a season four episode, she’d never officially travelled there as the writer. For “Something Unforgivable,” she got to make changes to the script as it evolved and give notes to Gould, who also directed.

“Getting to be there for all the rehearsals, watching the monitors, sitting in Video Village or over by Peter, watching him give feedback and seeing how he works, was really, really fun,” Levine said.

Something else that stuck with Levine: working with the incredible actors. When Rhea Seehorn, who plays Kim Wexler, was mentioned, Levine couldn’t contain herself. “She deserves all the awards, in perpetuity. She’s incredible, such a hard worker. And I love Kim’s story this season. She’s such a fascinating, interesting character.”

Once the shoot was over and the writers’ room called it quits for season five, Levine set an important meeting with Gould—the one where she’d ask to join the writing staff for season 6.

The one she prepared for by thinking a dozen steps ahead and imagining every direction the conversation could go.

Turns out, there was one direction she hadn’t envisioned.

“Before I could tell him what I wanted to talk about, he said, ‘I want you to be on staff next season,’” Levine said.

“And I went, ‘Oh, well then, I have nothing else I need to say!’”

Levine’s journey from post-production PA to staff writer was complete.

April 2020.

A lot has changed for Hollywood and the world at large. The emergence of COVID-19 and the shuttering of a large portion of the country has upended the U.S. economy, including the entertainment industry. Film and television shoots have been suspended. In lieu of in-person writers’ rooms, virtual rooms are emerging left and right. “Zoom conferencing” is the term du jour for rooms now, both new and old.

Count the "Better Call Saul" group among them. The team is hard at work breaking the sixth and final season, which AMC confirms will be a 13-episode run airing in 2021. Levine says “Zoom fatigue” is a real thing, but between making jokes and the occasional cat walking across someone’s screen, the writers’ room is settling into their new normal.

“It’s a challenge, it’s a pandemic. That’s tricky. We’re up and running and figuring it out,” Levine said.

“It’s of course always going to be different, but it’s not as different as I expected. We’re all still there talking about story.”

Season five’s finale aired a few weeks after the newest writer’s room convened. Though Levine had already seen the final cut—she co-wrote it, after all—watching it with her boyfriend was still an experience she was looking forward to. (In a twist, she didn’t get to watch it the way the rest of us did. She admits, sheepishly, that she doesn’t have access to AMC.)

If all goes as planned, Saul will be finished airing by the end of 2021, at which point Levine will hopefully be on to her next show. Her ultimate goal is to be a showrunner, but she’s in no rush to dive into something she’s ill-prepared for. She still clings to those desires she had way back when she was a post-PA on "Breaking Bad"’s final season. She wants to make sure she’s doing the best she can at whatever she does.

“Being a showrunner is the end game, but I’m not in a hurry,” Levine said.

“There’s a virtue to having a lot of experience before you step into that leadership role. You want to know the right way to do things, the wrong way to do things. It’s one thing to be a member or a part of the team. It’s another to be the person in charge. You have to learn and grow before you get there.”

Follow Ariel on: Twitter