Moments of Magic: Writer LaDarrion Williams and the Conjuring of 'Blood at the Root'

“Without access to creativity, I didn’t want to exist anymore.”

Does the world allow a Black Alabama-born boy from a financially disadvantaged background to dream big?

Growing up in the small town of Helena, LaDarrion Williams found himself drawn to the arts early in life. He re-enacted movie scenes. He wielded a make-believe magic wand saying, “I am LaDarrion Williams, and you are watching the Disney Channel.” He held concerts in the living room. As long as he could act, sing, and write, he was happy.

Those in his world thought of him as the odd man out. Why, they wondered, is a Black kid interested in anything other than sports? Is there something wrong with him? Doors that were open to others were locked to LaDarrion. He was ignored, disappointed, and discouraged. Not once or twice—so many times he stopped keeping track. When he worked 10 times harder than his peers, he was given a spot in the background. That, he was told without words, was where he belonged.

If that narrative is fed to a person over and over again, they’ll likely reach a point where they hit despondency and give up. LaDarrion didn’t. He couldn’t. He needed art to exist.

“The traditional route is the door, right?” he says. “But sometimes you have to climb in through the side window to get into the house. There, you unlock that door yourself.”

In the depths of LaDarrion’s being, a vision was taking shape. As a child, he was too little to understand. So he let himself be led by intuition. It took him on quite a journey—from Alabama and Tennessee to L.A., Nashville, Chicago, and New York. He invested every penny he made in his dream, even when it caused him to live on trains and in cars for several years. When the pandemic hit, he found himself amid the riots, fearing everything—the hatred, the virus, the lack of a roof over his head ... And, most of all, the future.

He turned to the higher forces he still believed in—his ancestors and God. His own God, not the one of the Southern Baptist culture he’d grown up with. He asked when his moment would come.

Had he not done the work? Had he not gone through enough hardships?

“I was having these outbursts,” he says, “because I was putting all I had into my career. There’s no return, I thought. At the time, I didn’t know I was planting the seeds.”

It took a long time, but reap he did. After years of having to make unthinkable choices, several magical moments occurred. Like all the bad things, all the good ones came at once. His biggest milestone to date was writing a New York Times Bestseller that catapulted him from the trenches to the top.

Despite this magnificent turn of events, LaDarrion’s life has been far from a fairytale.

“I always ask people to please, please not glorify the artist’s struggle,” he says, explaining he’s still healing from the scars inflicted during his journey toward the present.

And it’s in the present that I meet him. During our conversations, I’m struck by his optimism. When he talks about the thing he loves most—his art—his face creases into a wide, genuine smile. He radiates the uninhibited joy often seen in children. That’s remarkable for any 31-year-old, but especially for someone who’s faced the hardships that came LaDarrion’s way. Yet, despite his bright attitude, he never downplays the challenges that crossed his path. In fact, when I ask if it’s okay to address sensitive or complex topics, he immediately says, “Let’s get down to the nitty-gritty of it.”

LaDarrion calls out injustice when he sees it—or, to put it more accurately, lives it. But he hasn’t grown bitter. I quickly come to see that this is a man who deeply appreciates everything he has, tiny or major as it may be. Marveling at the beauty of post-downpour Pasadena fills him with just as much gratitude as signing a three-book deal with a Big Five publisher. Perhaps that’s because nothing has ever been handed to him. He’s had to fight for each of his possessions, both material and immaterial.

But here he is, on the other end of a stretched-out dark tunnel, cautiously enjoying the new era he’s entered. “Harsh weather will be coming again,” he says, “but now I’m prepared for it.” He’s referring to the troughs and peaks that characterize this life, of course. But we agree that the worst is hopefully behind him.

His story is not one of pure misery—or miraculous success, for that matter. It’s a nuanced personal history of an individual who found his purpose early in life, then empowered himself to realize it, even when the odds were very much against him.

LaDarrion carries within him the paradoxes that make humans infinitely intricate and interesting. He comes across as an optimist, yet he suffers from depression. In the depths of hopelessness, he tapped into a source of unwavering resilience. And with practically zero resources, he created a work that exceeds the sum of its parts.

“They just saw my size and the color of my skin.”

“I grew up in the Bible Belt, and that comes with special expectations,” LaDarrion tells me when I ask about his childhood. “There is church and there are sports. Where I’m from, young Black men didn’t see success until they were in the NFL or NBA. I had the size of a football player, so most teachers and coaches in high school said I needed to be on the football field. Some of them probably had the best intentions, but it was very limiting on a young Black student.”

Looking back, LaDarrion wonders why no one ever encouraged him to be a doctor or a lawyer. “They just saw my size and the color of my skin—nothing else. And it was very challenging for me, because I didn’t find any joy in sports.”

LaDarrion decided to follow his heart and act in school plays. When he was 17, scouts from prestigious New York and L.A. conservatories dropped by LaDarrion’s school. Several invited him to take their acting and theatre summer programs. Initially, he was over the moon. “A summer in New York represents a big, flashy life in a Southern boy’s eyes,” he says.

But when LaDarrion received the invoice and showed it to his mother, reality kicked in. “There was this harsh realization,” he says, “that I was a poor Black kid from Alabama with a single mother. The fee was $5,000—which really isn’t a lot, unless your mom has just enough to pay the bills.”

Determined to find a solution, LaDarrion went to one of the conservatories’ Financial Aid Offices. “I had to be the adult in that situation,” he explains. “So I asked if there were any scholarships available. They told me I had to pay the full amount or I couldn’t be a part of the acting program.”

Now, at 31, LaDarrion identifies this moment as the first huge setback in his career—not because he couldn’t take the summer program, but because it was the first time he realized he didn’t have the same access as other people. “There I was,” he says, “talking finances with people that were at least two times older than me, and the second I said my mom couldn’t write a check, they lost interest. The light in their eyes was gone.”

The only other student in LaDarrion’s school that was scouted was a Caucasian girl. LaDarrion remembers watching her mother hand the check to the theatre teacher. “That girl was very, very talented,” LaDarrion says. He goes on to describe her acting skills to me in detail. Not once does he speak ill of her. But to LaDarrion, the insouciance with which the girl’s mother delivered the check did confirm his lack of access and opportunity. After all, the two teenagers had both been invited to attend the summer program, because they were both talented. Yet, only one of them got to go to New York.

“I didn’t realize it at the time, but that moment greatly shaped me in my journey as a creative person,” he says. “I was 17, you know? I was on the cusp of getting out into the world, but I wasn’t yet ready to let high school go. I thought it was my safe haven. And suddenly, I couldn’t work on my art due to a lack of funds, resources, and support.”

“God, anybody, whoever exists—what is happening?”

It wasn’t only people at school who didn’t understand LaDarrion’s deep-seated desire to create art. There was a lack of support at home, too. “I don’t want to say I’m the only artist in my family, because I think we’re all innately creative,” he says. “But some people are afraid to go after it. I was the first person in my family who decided to pursue a creative career.”

LaDarrion felt his dreams were tolerated but not taken seriously. The people around him labeled his ambitions as either “cute” or “weird.” In LaDarrion’s family, success was defined as “making money from tangible endeavors.” And the problem was that, like most artists, LaDarrion had to spend a long time making art before he could earn a living from it.

Alone in his creative quest, LaDarrion turned to the place where every artist’s greatest work is born—his imagination. “As a kid, I considered it my safe space,” he says. “Every day, I went inside my head and dreamed up in-depth scenarios. I often lost track of time.”

But in the tangible world, time passed. Like most teenagers, LaDarrion explored his boundaries and made surprising discoveries about himself along the way—for example, in detention. “I got into trouble, and the teacher said we should either read a newspaper or a book,” he says. “I picked the book, which turned out to be a play—A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry. It changed my entire life. I felt encouraged to write a play in theatre class, which ended up placing first in a state-wide competition. Getting that award assured me into my purpose as a writer.”

LaDarrion was determined to break the generational chain, to do things differently than his parents and grandparents. But decisions like these come with practical hurdles. What if, for example, you deeply wish to attend college, but you’ve never heard of a college application? “I genuinely didn’t know what that was,” LaDarrion says. “And when I figured it out, I realized I didn’t have the necessary tools to prepare myself for the application—which, by the way, cost $60. I didn’t have that kind of money.”

By the time he graduated from high school, LaDarrion was too late to apply for college. He took the year off—not to give up on his plans, but to flesh them out. Little did he know that over the next few months, he’d feel increasingly lost. “I didn’t take any formal playwriting, acting, or singing classes,” he says, “because I simply couldn’t afford them. And in my family, you either go to school or you get a job. Any job. That’s the expectation. There's nothing wrong with that, but that was just a life I couldn’t live.”

When LaDarrion researched the options, he found a great college playwriting program not too far from home. He applied and got accepted into the theatre department. But he still had to pass the ACT. Since he learned about it late in the process, he wasn’t able to do the necessary prep work.

He failed the exam.

“I was very depressed,” he says. “I didn’t know what to do with my life.”

LaDarrion took a job at Taco Bell. Down the street was a community college, so he figured he should take some classes. If he’d brush up on math, English, and science, he thought, he might transfer some credits and get his college degree after all.

When this idea turned out to be unfeasible, LaDarrion was hurled into an adolescent existential crisis. “I was like, ‘God, anybody, whoever exists—what is happening? I’m trying to go to college. I’m trying to be better. I want to study and be an artist. Why are all roads being blocked for me?’”

“It’s great to have big dreams, but we need little dreams along the way.”

One thing I notice about LaDarrion: he’s very candid. For example, he discusses his struggles with depression and houselessness in such an open, matter-of-fact way. But whenever he talks about his younger self, his eyes turn to the ceiling, and he briefly retreats into himself—a blend of sympathy, pain, and tenderness crossing his face. In these moments, I assume he's picturing young LaDarrion—the child, the adolescent, and the 20-something who’ll run into seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Many times, he will think this is the biggest curve ball life has thrown him. He’ll face it head-on, not knowing it’s going to get worse before it gets better.

“A Black person’s innocence is stripped away from them at a young age,” he says. “We're not allowed to dream.”

Throughout our conversations, it becomes clear that 31-year-old LaDarrion wishes he could tell those younger versions of himself they should continue to dream. Trials and tribulations will inevitably come, but life will be kind one day. Not now, though. Not yet. Until he is introduced to those who want and need to hear his voice, he’ll have to rely on himself.

The first time he felt completely alone was during that post-high school year. “I had friends, but I really spent it in solitude,” he says. “I went through life merely existing. That’s very tough on a 19-year-old’s shoulders. As a creative person, I felt the world in a different way.”

A few months later, a new journey finally presented itself. A letter he’d written on a whim turned out to be his ticket into college. “I was so excited that I got to be a college student,” he says. Even now, more than a decade later, his face is beaming at the memory of the brief happy spell that followed. “That summer, between going to college and working at Taco Bell, I went to Disney World for the very first time. Growing up, I’d never gotten to go, because we couldn’t afford it. So I walked around Disney World as a six-foot-three, 200-pound Black man, and I got to be a kid again.”

He smiles from ear to ear, visibly reliving the joy of that day. “I got to live out that little dream, you know? And I think we should all have those. It’s great to have big dreams, but we need little dreams along the way. When I entered those gates, I smelled the candy and saw the characters, and I just became a big kid. It’s important to have moments like those. They keep the fire of creativity going.”

“The harder you fight, the more you’re going to be pushed to the sidelines.”

Shortly after settling into his dorm room, LaDarrion ran into practical issues. He didn’t have money for books. With no car, he couldn’t go to the grocery store without the help of fellow students. But by that time, he’d gotten used to working his way around problems. He met other theatre majors and made some friends. “At first, I thought it was great,” he says. “People were nice. But then we had to audition for plays, and I quickly discovered I wouldn’t get the types of roles I wanted.”

The first part LaDarrion played was that of a slave in Big River: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. He wondered if they were going to do other types of plays, too—works he and his fellow Black theatre majors would recognize themselves in. But LaDarrion didn’t speak up at the time, as he had finally gotten into college, and he’d vowed to be the best student he could be.

He received a theatre scholarship, which he was grateful for because it helped him pay for his dorm room. But he increasingly felt as if he was allowed to be there as long as he accepted he’d always play a supporting role—both in plays and in real life.

As a theatre major, he auditioned a lot, yet never got any parts that helped him grow as an actor. “I realized I had to work 10 times harder to get half of what my white fellow students got,” he says. “I can only speak to my own experience, but I felt that there was a very weird energy towards Black students. It didn’t feel like we were truly welcome.”

To clarify what he means, LaDarrion provides an example:

At some point, he joined a group of students who put up a show. He received lots of praise for the part he played, but his success was short-lived. The following year, he got to play the same character, but his part was considerably decreased. “I think that for people like me, there’s a different ‘rule:’ the harder you fight, the more you’re going to be pushed to the sidelines. That was a revelation I got as an artist. At some point, I had to acknowledge it to myself—‘LaDarrion, you’re only significant in the background.’”

That manifested in a grim way after the Trayvon Martin shooting in 2012. Protests were held across the U.S., and LaDarrion’s mother called to tell him he shouldn’t wear his hoodie.

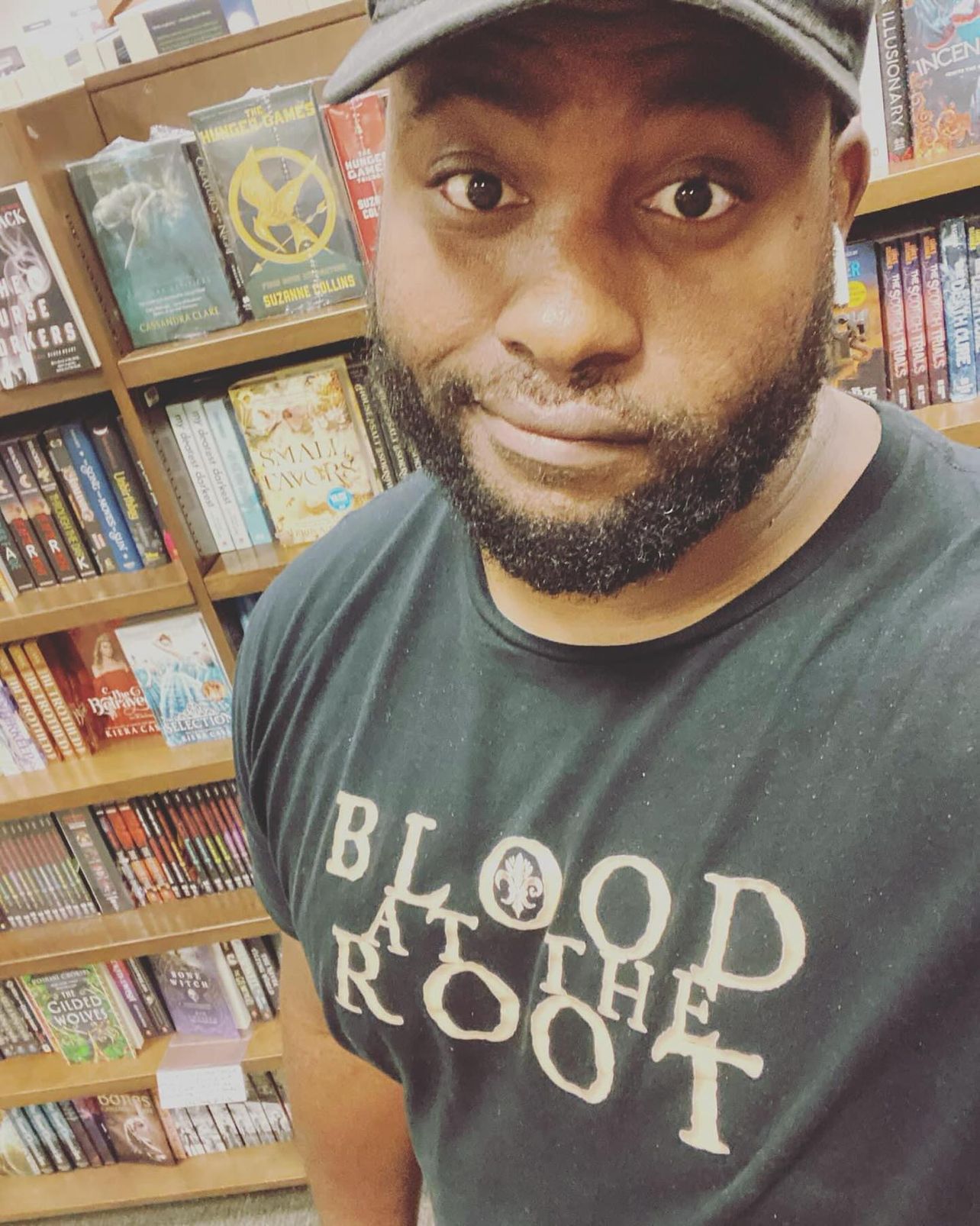

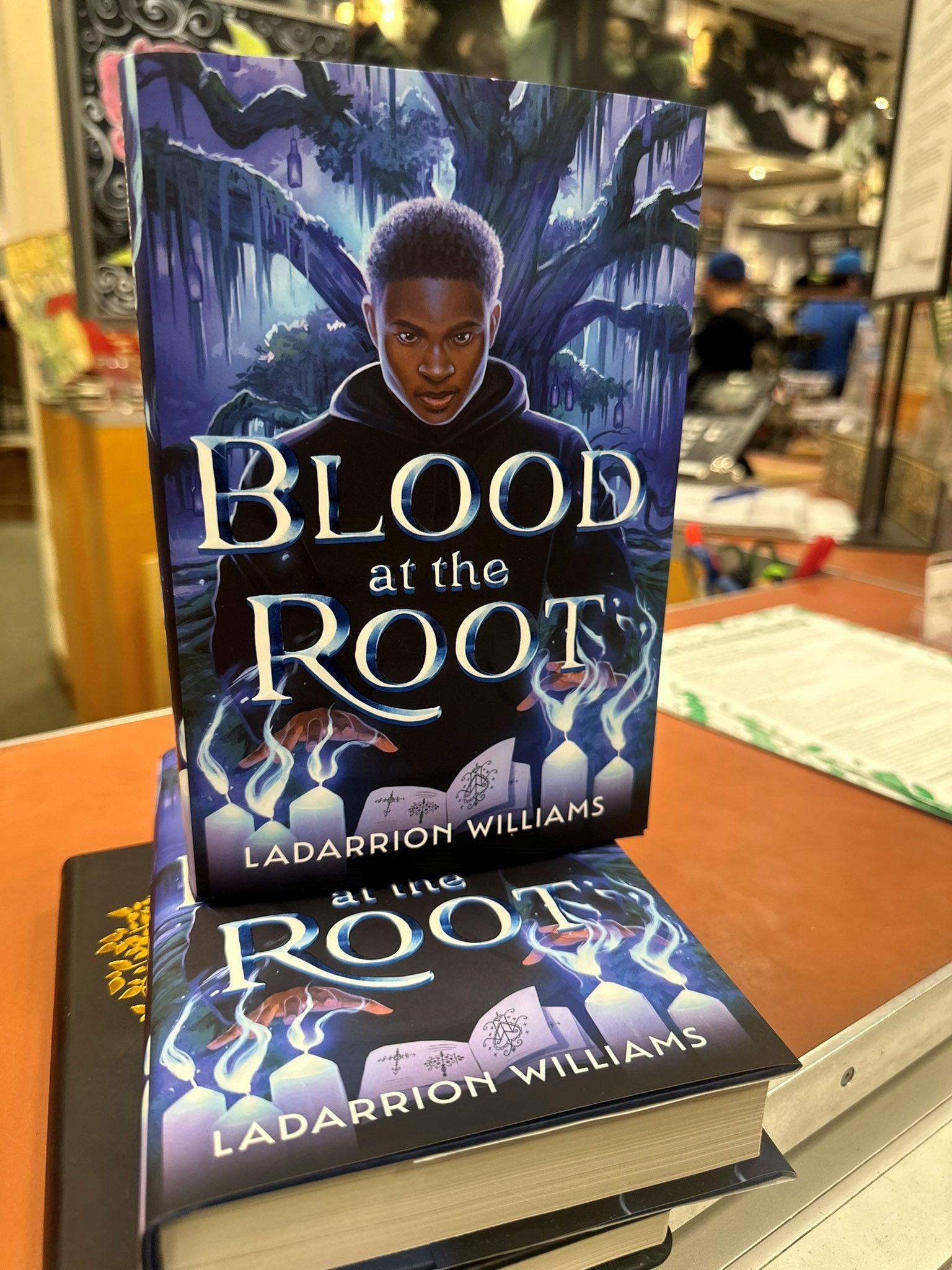

(On the cover of his 2024 debut YA novel, Blood at the Root, we see the protagonist, a Black boy, wearing a hoodie—LaDarrion wanted to combat the association of his favorite piece of clothing with crime.)

LaDarrion was afraid. He wanted to talk about it, but his environment didn’t seem to feel the same way. “We were not having conversations about it in the classroom,” LaDarrion says. “Professors didn’t ask me if I was okay—if my mental health was okay. I would have wanted someone to be like, ‘Hey, I know there isn’t a big Black population here, but how are you doing?’ I realized we lived in two different worlds. Mine was affected. Theirs wasn’t.”

LaDarrion found it all the more concerning because they had recently put up Big River: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. He explains, “A line in one of the songs is, free at last. And what was happening here—well, that’s not freedom to me. But amen.”

At first, LaDarrion thought nobody really cared. But when his fellow students misspelled another Black student’s name as ‘Trayvon Martin’ in a play’s program, the energy shifted. LaDarrion explains how his friend’s first name sounded the same, but it was pretty much impossible to mistake his surname for ‘Martin.’ “It was purposeful,” he says. “I think it was supposed to be a joke. And these were Christian people. All that time I’d thought, Cool, they’re all about love. So when they did this, I was very confused. My friend and I were just like, ‘Really? They really did that?’ Now, we look back and go, ‘Why did we not say anything?’”

He can perfectly answer that question, though. “I think you have to just sit there and take it. Because it’s like, This is all we have. And I didn’t really feel safe there.”

That sentiment only increased when Barack Obama won the 2012 election and LaDarrion watched a white student crack the pool table in a fit of rage. “I saw the hate over that victory,” he says. “This was someone who used to sing worship songs every week. How Great Is Our God. I don’t think Jesus would react that way. But I may be wrong.”

“I was being fed creatively by the works of these artists I’d discovered myself.”

In his sophomore year, LaDarrion became jaded with the whole college experience. He didn’t find himself in an environment he’d envisioned—one where he could freely explore and develop his creativity. The wish to be challenged as an artist grew stronger. If he couldn’t act, LaDarrion figured, he’d go back to that other love of his—writing.

“I took playwriting and play analysis classes,” he says. “And I sure loved learning about Greek theatre. But I did wonder where the Black playwrights were. I had read August Wilson and Lorraine Hansberry, and I thought to myself, These can’t be the only Black playwrights out there.”

LaDarrion decided to do his own research and stumbled upon Dominique Morisseau, Katori Hall, and Tarell Alvin McCraney. Reading these playwrights’ works changed him profoundly. “I was being fed creatively—not by the institution that was supposed to do that, but by the works of these artists I’d discovered myself.”

Over the summer, when LaDarrion went back home to work at Taco Bell, he wanted to save up for books and food so he’d get through the next semester. But something happened with his financial aid, and he had a choice to make—drop out of college or pay the full tuition first and try to get financial aid afterwards. “I had no idea where to find the money,” he says, “but I also asked myself if I really wanted to go back. I was tired of paying all this money without getting the full experience.”

To the surprise of his friends and professors, LaDarrion decided not to return.

The big question was, Now what?

“If you don’t have access, you have to find or create it yourself.”

Over the next few months, LaDarrion sank deeper and deeper into depression. “Without access to creativity, I didn’t want to exist anymore,” he says. “I couldn’t work on my art, and I just died a little. Many of my friends and family members didn’t get that. They didn’t understand where I was coming from.”

LaDarrion’s solution came when he got a car. Now, he could drive to Birmingham and audition for plays. The first main part he got was in a children's play. It was a milestone—he could finally call himself a professional actor. “That was the first time I got paid as an artist,” he says. “It proved to me that I could do this. And when my family came to my play, they were like, ‘Oh, you’re really good.’”

Around that time, LaDarrion also fell in love with TV writing. He wasn’t sure how to become a TV writer. But to pursue a creative career, he believed, he should move to New York or LA.

By now, though, LaDarrion had accepted that his was not a conventional journey.

“I had tried to mold myself and fit myself into a traditional box,” he says. “It took me a long time to embrace the fact that I'm not a traditional person. My upbringing was different than that of others, and so is my outlook on creative endeavors. And through all those little revelations in previous years, I’d learned one thing—if you don’t have access, you have to find or create it yourself.”

Throughout our conversations, I come to know LaDarrion as resolute, with a strong vision. His existential crises were not spurred by the age-old question, Why am I here? Depression visited him when he couldn’t do what he believes—or rather, knows—he was born to do. It knocked him down, but never enough to quit. In fact, the only way to survive was to keep making art. And in the process, LaDarrion held onto his inner child.

When I ask if that kid is still alive inside of him, he says, “Oh, he’s still there. Since I’ve started writing books, I have been talking to 17-year-old LaDarrion. He needs some healing. He needs some love. And he shows up in my work, you know?”

“I was so close to my dream, but I was literally separated from it by a gate.”

In many ways, the 2024 release of LaDarrion’s debut novel, Blood at the Root, was a dream come true. But the road to publication was the opposite. There were times when despair tried to get the better of him. Did it wear him down at times? Absolutely. But he maintained his eye for nuance, even when discussing situations of sheer injustice. He doesn’t seem to hold grudges, and he repeatedly expresses love and appreciation for his friends.

One of them is Mildred Marie Langford, who goes by ‘Millie.’

It quickly becomes clear to me that theirs is one of those rare, deep friendships tested by real-world obstacles. LaDarrion and Millie have proven to have each other’s backs, and they talk about each other with genuine warmth.

“LaDarrion is a wonderful friend and a beautiful person on the inside and out,” Millie says when I ask her how she’d describe him. “You can see the hard work, the talent, and the dedication. If you have a friend like that, you’re willing to be his ride and die.”

A writer, actor, producer, and content creator herself, Millie says being LaDarrion’s friend has helped build her own confidence as an artist. “Seeing how he remained diligent in the challenges he faced has made me more determined to make things happen.”

The challenges she refers to are those LaDarrion encountered in L.A., where he moved in 2015. It would take a while before she’d meet him, but she was there through several of his hardships. “People weren't really able to give him what he was looking for at the time,” she says. “But he stayed in the race and never gave up on himself. He believes in himself at such a profound level.”

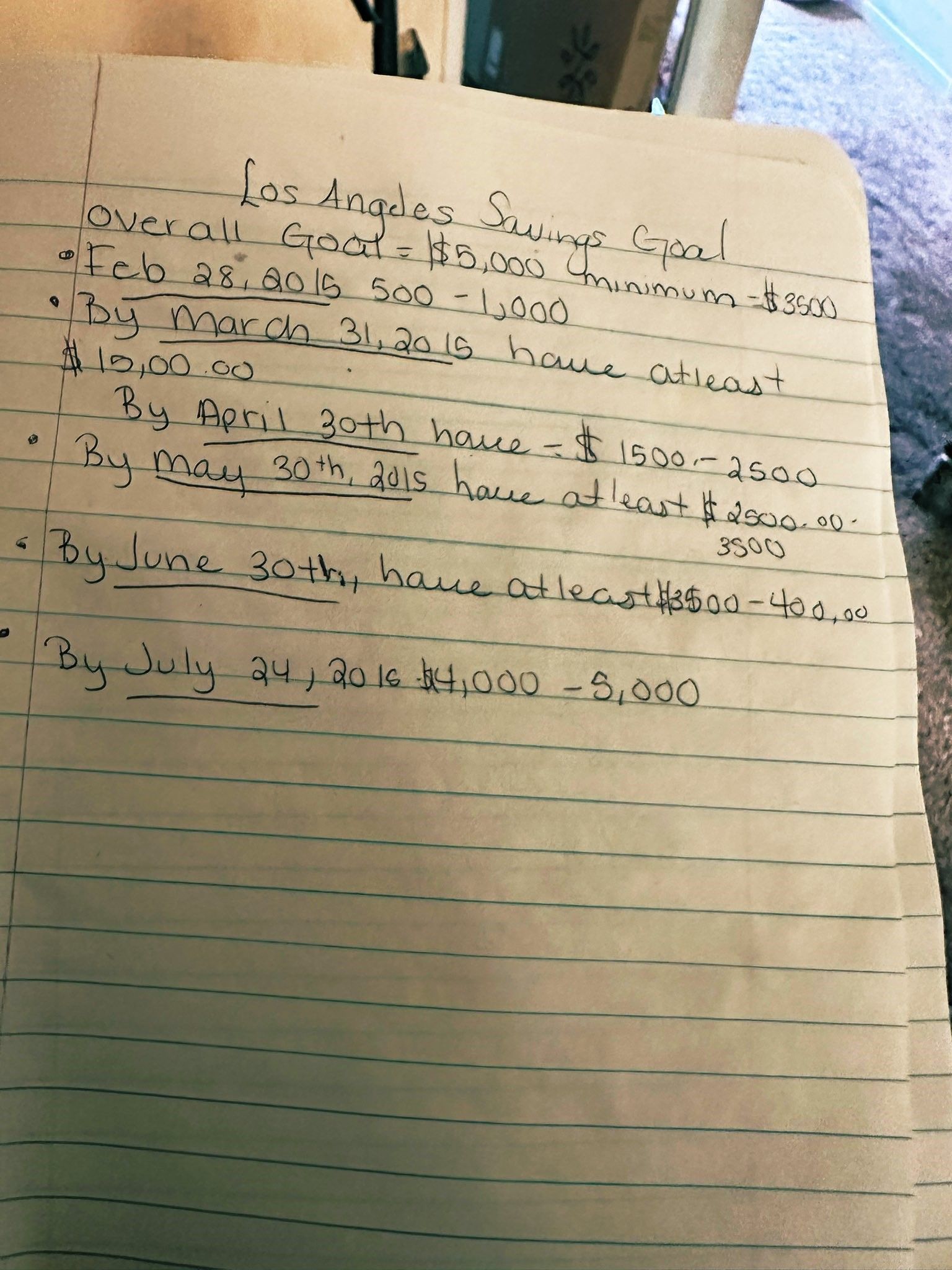

When LaDarrion arrived in L.A. with a feature, a TV pilot script, and approximately $3,500, he didn’t know he’d have to be that resilient. Unfamiliar with the workings of the industry, he thought it would be fairly easy to become a TV writer.

“I thought it was like applying for a job at a fast food chain,” he says, smiling at his own naiveness. “I had never been out of the South before. I didn’t even know what guacamole was.”

He got a job at Universal Studios and worked on his scripts during breaks.

“I was that dreamer, you know?” he says. “I was that kid who looked at the iconic movie studio and thought, One day, I’m going to have my own parking space here. I’ll walk into my production office, write my scripts, and go to set. And I’ll have my own name plate that reads, ‘L. Williams.’”

At first, he found it inspiring to watch how movie sets were built and casts and crews arrived. But after a while, a yearning feeling crept in. “Working there gave me fuel, but at the same time I was using a lot of fuel,” he says. “I felt like a car that just sits idle, burning gas. It was hard to go to work. I was so close to my dream, but I was literally separated from it by a gate.”

“After a year and a half, the L.A. blues started to set in.”

One thing that improved a bit for LaDarrion in L.A. was his access to resources. Although he couldn’t afford to take any writing or acting classes, he discovered a gold mine at the Writers Guild Foundation. “When I learned about their library, I went there and read all the scripts,” he says.

At home, he scoured the internet to glean all the craft information he could find. Armed with new knowledge, he rewrote his scripts and began to submit them to contests. It was an expensive endeavor. It’s never easy to win a contest, but for a writer who’s in the middle of teaching themselves the craft, it's virtually impossible.

Meanwhile, LaDarrion struggled with practical concerns. He lived in what he calls a “little shoebox studio,” which he shared with a roommate. Daily errands exceeded his tight budget. Sometimes, he still had a week left until his next wage.

He wanted to act in plays, but that plan hit a cul-de-sac. “I couldn’t go to rehearsals,” he explains. “Then I’d miss work and wouldn’t be able to eat, pay my rent, or finance my writing. Since I really wanted to be creative, I considered shooting a film. But I had no idea where to start. I didn’t know how much it cost, and I didn’t have any actor friends in L.A.”

A world LaDarrion was more familiar with was that of playwriting. So he submitted his plays to competitions and theatres across the country. But he wasn’t getting any playwriting opportunities, either.

When people back home inquired about his progress, he didn’t know what to say. “After a year and a half, the L.A. blues started to set in,” he says. “I was a kid from the South trying to survive on his own. I was still acclimating myself to L.A. life. And I was spending my all on my dream.”

To combat this, LaDarrion took matters into his own hands. If he wasn’t given any opportunities to work on his art, he’d create one himself. He decided to put up a play he’d written about voting rights in 1960 Mississippi. At first, people didn’t show up at his auditions. But eventually, he assembled a group of actors, found a 40-seat theatre, and rented a rehearsal space. Every paycheck he received went into the project. It didn’t yield any profit, but LaDarrion did gain a ton of experience. He made something tangible. And, perhaps most importantly, he was introduced to creatives he’d come to call collaborators and friends.

“I moved out of the room and into the car.”

LaDarrion’s decision to invest in his art came with a steep price. When he and his roommate got into a fight, LaDarrion packed up his stuff and went to the Hollywood/Vine train station. There, a harsh truth dawned on him—he had no money and nowhere to go.

Many days of insecurity followed. On some nights, he slept on trains. On others, he’d wait until after 9 p.m. to take a shower and a nap at Universal Studios’ break rooms. When he got fired from his job, he felt the ground slipping from under his feet. He lost his income and his occasional nightly safe haven.

On top of that, his play died. “I didn’t have any money to pay the actors, so everybody quit,” he says. “And with no access to Universal Studios, I could only spend my nights on trains and shower at a friend’s house. Sometimes I’d sleep on their floor or get a cheap little hotel room for the night.”

After a brief stint of working at a fast food chain—where LaDarrion could eat for free—he ended up getting a job at Target. He moved into a house for artists, where he paid a few hundred dollars for a room he shared with four other people. There was no space in his life to work constructively on his art. Surviving took up all his time. Depression hit him once again, but he was determined to crawl out of the abyss.

In 2017, LaDarrion got accepted as an Uber driver and got a car. That’s when he made a radical decision. “I moved out of the room and into the car,” he says. “I figured if I slept there, I wouldn’t have to pay rent. I could stack up and do another play or film. So I told myself I could do it.”

As it turned out, he could. LaDarrion’s first short film, Katrina, was based on a play he’d written in high school. He made it with a couple of friends he’d met during stage readings he organized. “I couldn’t put up a full play with all the bells and whistles,” he says, “but I could at least do these readings to try and build my name as a playwright. There, I met fellow artists who wanted to write and act, just like me. Several of them are still my friends today.”

At the time, only a few knew that LaDarrion was living in his car. Among them was Millie, though she had to probe him to learn the truth. When she tells me about the moment she found out, she still seems upset. She explains, “I asked him why he chose to do this. I said, ‘You know me. You have friends. Why didn’t you tell us?’ But I think it was pride, you know?”

For a while, LaDarrion stayed on Millie’s couch. After that, she arranged for him to stay at a mutual friend’s house. But, LaDarrion tells me, these were temporary solutions. He didn’t want to burden his friends, one of whom got into trouble with his roommate when LaDarrion slept on the couch. “It was a tough time for all of us,” LaDarrion says. “The artist’s life is a rollercoaster. You go up and down, up and down.”

When LaDarrion’s loved ones in Alabama learned about his living situation, they were shocked. They urged him to come home, but he didn’t.

“I had a vision,” he says. “I could see it. I just needed to keep going.”

“What if you don’t make it?”

When I ask about the timeline, LaDarrion starts to sum up the events as if relaying a news item.

Somewhere halfway, he interrupts himself.

“Oh my God,” he gasps. “Looking back, I can’t believe I was doing this.” He pauses, and his eyes fill with a sense of wonder. “I still drive by there some days. I might do it today—just go to the spot where I used to sleep, sit there, and say, ‘Look how far you’ve come.’”

That spot used to be his little corner in the world. He describes it to me in detail—from the greenery he watched from behind the wheel to the bed sheets he kept in the trunk. While living in his car, LaDarrion made sure to maintain a routine. “I would wake up between 7 and 8 a.m.,” he says. “I always tried to shower, either at a friend’s house or at the gym. Then, I’d work as an Uber driver until around midnight. My days usually ended at a parking lot in North Hollywood, where I’d use a fast food restaurant’s bathroom to take care of myself.”

One morning, around 5 a.m., a police officer came to talk to LaDarrion. “They’d gotten complaints about me sleeping there,” he recalls. “I told him I was an Uber driver trying to survive, and this was my base. I said I didn’t like to drive when I was really tired. The officer was very nice. But that was a scary moment for me.”

And then there was the long-term fear. How many tomorrows like these still awaited him? “I thought, Man, the odds are literally stacked against you,” he says. “What if you don’t make it? I can’t verbalize what I tapped into, or where that resilience came from. I just knew I had a vision for my stories. I knew what I wanted.”

“‘We are your friends,’ they said, ‘and we love you.’”

In 2019, LaDarrion felt like he was wading through an invisible swamp. “I was putting all I had into my writing career,” he says, “and it wasn’t happening for me. I was tired of doing it.”

And still, he continued to write new plays and organize stage readings. People would often come up to him afterwards, asking why his plays were not produced all over the country. He jokingly told them they should let theatres know that. In the meantime, he kept submitting his work whenever he could. It was turned down—over and over again.

LaDarrion’s friends encouraged him to charge people for attending his stage readings. Ultimately, he listened to them. He didn’t make much, but he wanted to give the actors a stipend. “They asked me why I was paying them,” he says, still touched by the memory. “They wanted me to keep it. ‘We're your friends,’ they said, ‘and we love you.’”

LaDarrion says it was an emotional time. He felt deeply discouraged. But on the verge of burnout, he got accepted into a playwriting residence in Omaha, Nebraska. For the first time in his life, he was flown out to develop a play. Not only did he get paid, but he also got a temporary room to stay in. “I hadn’t slept in a bed in such a long time,” he says. “So when I arrived, I just wanted to lie down for a while.”

After finishing the project, he had to return to L.A. To reality. Once again, his car was his house—until it wasn’t.

At some point, LaDarrion lost his car. What followed was a volatile time. While staying on a friend’s couch, he diligently applied for jobs (without getting hired) and kept on writing. Eventually, an old college friend moved to L.A. and let LaDarrion borrow his car for a year.

Slowly, life took a turn for the better. He went back to being an Uber driver. A theatre in Hollywood offered to produce one of his plays. A New York theatre scheduled a workshop production of another play. LaDarrion felt cautiously optimistic.

When he tells me this, he smiles a painful smile. “This is January 2020,” he says. “And we all know what happens a month later.”

“It’s getting bad out here, and your mental health is deteriorating.”

When the pandemic hit and the world shut down, LaDarrion lost the little stability he had left. Since his friends couldn’t risk getting sick, he could no longer come over to shower or spend a night on someone’s couch. Riots broke out, turning the streets into a dangerous place to be. Amid civil unrest, with a virus raging around the world, LaDarrion continued to sleep in his car. “It really wasn’t safe,” he says. “That’s when I said to myself, I can’t do this anymore.”

He learned about the Dramatists Guild of America’s Emergency Grants and applied, including pictures of life in his car. When he received a $10,000 grant, he could barely believe it. “I’d never seen that much money in my account,” he says. “I could finally find myself a place to stay.”

Easier said than done, as LaDarrion’s credit score wasn’t up to par. But in April 2020, he found a room through Facebook. Someone was urgently looking for a new roommate, and LaDarrion could pay the first month’s rent right away.

His move-in marked the beginning of a new era. “I finally had a house again,” he says. “I had my own room. I could lie flat on a bed. Not a car seat, but a bed. I spent the first two or three days just lying there.”

Having been through an ordeal, LaDarrion is keen to warn young creatives against romanticizing the struggling artist’s life.

“Of course I had a vision,” he says. “But when you don’t have some basic necessities—like, the ability to shower and use the bathroom at your leisure—it will mess with you mentally. That happened to me. It came to a time where I had to choose my mental health. The dream will always be there, I told myself. The want, the need, and the vision won’t go away. But it’s getting bad out here, and your mental health is deteriorating.”

“The story wasn’t leaving me alone.”

With a stable place to live, LaDarrion found the peace of mind he’d lacked all those years. “I could drive down the road to get food,” he says. “I had a writing desk, so I wrote a lot more. It was just beautiful. I slowly started to heal from those years of living in my car. I am really grateful for that time, because it set me up for what I’m experiencing now.”

He’s referring to the release of Blood at the Root, which started with a tweet he wrote in his new room—“What if Harry Potter went to an HBCU in the South?” The post went viral. People sent him money to make that movie. In October 2020, at the height of the pandemic, he turned the idea into a short film, which he made with Millie and other friends.

“I thought it was finally going to happen,” LaDarrion says. “The short was getting traction, and I signed with a manager.” Other things went uphill, too. When LaDarrion’s lease was up, he found himself a studio apartment in North Hollywood. “I got to have my own home and be by myself for a while. That allowed me to heal a bit more.”

But after some initial success, LaDarrion felt that he hit a wall with Blood at the Root. Despite the enthusiasm on social media and the short he’d made, the project didn’t get picked up. “It broke my heart,” he says, “because the story wasn’t leaving me alone.”

Friends suggested that LaDarrion turn it into a book. To explore the market, he got back into an old love of his—reading. He went to a bookstore and asked for help to find YA fantasy books with a Black main character. The sales rep took him to the right department. They went over all the books but only found two with a Black kid as the protagonist—and even these works didn’t fit LaDarrion’s request. “Both revolved around police brutality,” he says. “It was in the aftermath of the riots. I said, ‘Look, these are very important stories to tell. But this is not what I want to read right now.’”

LaDarrion was looking for a Black Harry Potter or math prodigy. He wanted a Black teenager to be the protagonist of their own love story or travel around the world in 80 days. “Not all stories have to be about racism and financial disparity,” he says. “Yes, these issues are very real, and they’re in my face every day. I’ve had to deal with them my whole life. But there has to be a balance. Books, movies, and TV shows are very powerful. They should offer a mix between real life and fiction.”

During our conversations, LaDarrion explains he wants to show young Black readers that it’s okay to have dreams and ambitions. He believes they should not only have valiant heroes, but also nuanced protagonists that go through universal struggles—regardless of the color of their skin or the family they were born into.

“We all grow up in different environments, and not everybody can get certain types of life lessons at home,” he says. “So if kids meet a character who is like them and who’s going through the same things, they can follow that character. It shows them that a different outcome is possible.”

When we discuss this in-depth, LaDarrion comes up with a range of ideas. “I want to see Black kids who are chess players and scientists,” he says. “Or how about a coming-of-age story about a Black teenager who just graduated from high school and doesn’t have any guidance in life? Or a Black kid that spends their college fund on travel?” At this point, he’s gesturing cheerfully. “I’m sorry if I’m all over the place, but I get so passionate about that type of storytelling.”

There is, of course, no need to apologize. His sincere enthusiasm is contagious. I tell him he should write all these stories. He says he just might, since he has always craved them. As a boy, he watched kids in movies and TV shows accomplish amazing things and go on exciting adventures. He wanted to be like them. But it was difficult to imagine, as these works depicted Caucasian characters who lived in environments worlds apart from his. He tells me he often wondered, “Can we have one, please—one story about universal issues that makes us the center of our own narrative?”

When he stood in that bookstore, the little boy from Alabama with big dreams emerged from hibernation, quietly telling LaDarrion to do something about it. He went back to his studio apartment, locked himself in, and wrote the first draft of Blood at the Root. It took him 12 days. “It poured out of me,” he says. “I had the TV pilot script and the short, but a book requires much more. So I built this whole world and fleshed out more characters. And I fell in love with the story all over again.”

“Suddenly, the tables were turned.”

When LaDarrion finished writing his manuscript, he assumed the publishing industry wouldn’t be open to a Black teenage protagonist who isn’t dealing with racism or police brutality. So he planned on self-publishing the book. To fine-tune the manuscript, he hired a professional editor. As they worked together to get it in shape, she encouraged him to try the traditional publishing route.

LaDarrion was skeptical, but his editor—who has become a friend of his since—believed traditional publishing needed this type of story, and he’d get a major deal. In April 2021, LaDarrion decided to give it a shot. He queried hundreds of agents. Rejections filled his inbox from day one. “I was being petty,” he laughs. “I sent every single rejection letter to my editor saying, ‘See, I told you so.’ But she said she was there for me, and I should keep going.”

One morning in July, LaDarrion woke up to a life-changing email. It contained an offer for representation from a reputable literary agent. Other agents were still reading his manuscript. As is customary in the querying process, LaDarrion let them know about the offer and asked if they could get back to him in case they were interested. Two other agents wanted to represent him. When he thinks back to this moment, he smiles in slight disbelief. “Suddenly, the tables were turned,” he says. “Agents tried to convince me to work with them, explaining their editorial vision for the book. I listened carefully and did my research on all three of them. By August, I made my decision.”

LaDarrion signed with Pete Knapp, literary agent and partner at Park & Fine Literary and Media. Even though it’s been nearly three years since Pete was first introduced to Blood at the Root, he tells me he vividly remembers that moment. “I was on the L train from Brooklyn to Manhattan when I read the first 10 pages, which LaDarrion had initially sent me to read,” he says. “I immediately wrote to my colleague, ‘We’ve got to bring this in.’ There’s something about the beginning of the book that really brought me straight into the world LaDarrion has created—and then he carries that through in such a hugely convincing way.”

Pete believes LaDarrion’s background in playwriting and screenwriting impacted the way in which he crafted the book. He explains, “The dialogue is punchy, and there’s a strong visual element to the fantastical world he’s created—which has been rooted in real characters that feel very much of our world.”

The main character, a 17-year-old Black boy called Malik, carries within him the elements LaDarrion has discussed in-depth during our conversations. Malik is looking for answers about his heritage, his uncontrollable powers, and his past. When he ends up at an HBCU for the young, Black, and magical, his first love reappears, and he gets acquainted with a future he’d never envisioned for himself.

One of the things Pete highlights is Malik’s interior world. “Like the world of Caiman University, it’s so fully realized,” he says. When I ask why Pete decided to take a chance on Blood at the Root, he says he didn’t feel like he was taking a risk. “I remember my colleague and I had this conversation about the book, and we both thought it was big and exciting.”

“A lot of his resilience comes from his steadfast belief in what he’s doing.”

LaDarrion and Pete worked on the book for a whole year. On September 19th, 2022, they deemed it ready to submit to publishers. LaDarrion says, “I was still claiming they wouldn’t want this story because it’d be out of their comfort zone.”

Nevertheless, he’d gotten his hopes up. So he set himself a goal—to get a book deal before his 30th birthday in December. “It didn’t come, obviously,” he laughs, “and I was being very dramatic. ‘They don’t want my book,’ I said—even though it had barely been three months since it had gone on submission.”

It seems as if LaDarrion was only having a moment, because he doesn’t come across as a pessimist. What I notice during our conversations is that he tends to focus on what works—or what can work. To LaDarrion, a problem isn’t a dead end. It’s the beginning of a solution.

Pete, too, describes LaDarrion as someone who keeps moving forward. “From the first time I met him, it was clear he wasn’t really interested in obstacles,” he says. “He was just interested in where he was going and in getting there. To his huge credit, that has been how he’s operated. He's faced a lot of different hurdles, but it’s amazing how little that has slowed him down.”

When we discuss LaDarrion’s ability to not only survive but also reject setbacks, Pete says, “I feel like a lot of his resilience comes from his steadfast belief in what he’s doing. He is so driven by his mission and his creative passion.”

I ask if Pete believes that’s why LaDarrion should be one of the voices that bring representation and agency to Black characters in fiction. “Well, for one, he’s a fantastic writer,” Pete says. “It starts there. He’s written a great book. But yes, he has the energy and personal drive to be one of those voices. I think he knows what a difference this work can make for readers, because it would have made a difference for him. It could have changed his own experience growing up.”

“I wrote this play in my car, and three years later it got a world premiere.”

From 2020 onwards, LaDarrion has gradually found his audience. In addition to shooting the short film and signing with Pete, he placed as a finalist in the 2021 Script Pipeline TV Writing Contest with the TV script version of Blood at the Root. In 2022, while LaDarrion waited to hear back from publishers, Millie submitted his play Boulevard of Bold Dreams to TimeLine Theatre Company in Chicago. In January 2023, he was flown out to develop it.

While working on the play in Chicago, he got his first offer from a publisher. Two more offers followed. On January 19th, 2023—exactly four months after his book went on submission—LaDarrion signed a three-book deal with Labyrinth Road, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

The tide of life had turned in his favor. On February 1st, 2023, Boulevard of Bold Dreams had its world premiere at TimeLine Theatre Company, receiving critical acclaim. “I got to be a playwright,” LaDarrion says in a humble voice. “I didn’t have to pay for rehearsals. I didn’t have to go around town to buy pencils and highlighters and food for the actors. I had a stage manager who wanted to know if I was okay and who asked if I needed the scripts printed off.”

Attending the premiere was like entering a different reality. “I got to see my play,” he says, still filled with wonder. “I got to see the carpet, the chairs, the piano, and the bottles that glittered on the bar. Everything was exactly how I’d imagined it to be.”

I ask if that was a magical moment for him. “Absolutely,” he says. “I wrote this play in my car, and three years later it got a world premiere in one of the greatest cities for theatre. And from there, it went to Greater Boston Stage Company and Orlando Shakes. I had three major productions across the country in one year.”

LaDarrion didn’t want the play’s journey to end there. In November 2023, he asked Millie to hop on a plane to New York with him. There, he rented a theatre and organized a one-night-only stage reading of Boulevard of Bold Dreams. “I spent my own money on it. I took a chance there, because I deeply believe in this story. I don’t know if anything will come from it. But I think I planted a seed, just like I did all those other times.”

When time comes to reap what he’s sown, he says, Millie will be on board. “If there’s going to be a movie, I’m going to fight for her.”

When I share this quote with Millie, she is moved. But she’s mostly proud of her friend’s accomplishments. “When the play premiered in Chicago, it was wonderful to see the joy on his face,” she says. “He had worked so hard to make it happen. To be part of that journey and have that experience with him was really exciting.”

It was a lovely night for Millie, too, as she has always believed in LaDarrion. She explains, “The first time I was introduced to LaDarrion and his work as a playwright, I was like, ‘Oh my God. This is so good and powerful.’ He had quite a mature voice for someone so young. That’s really where our friendship took off.”

“I went through everything You gave me, and I’ve survived and conquered.”

Our conversations take place in the first quarter of 2024.

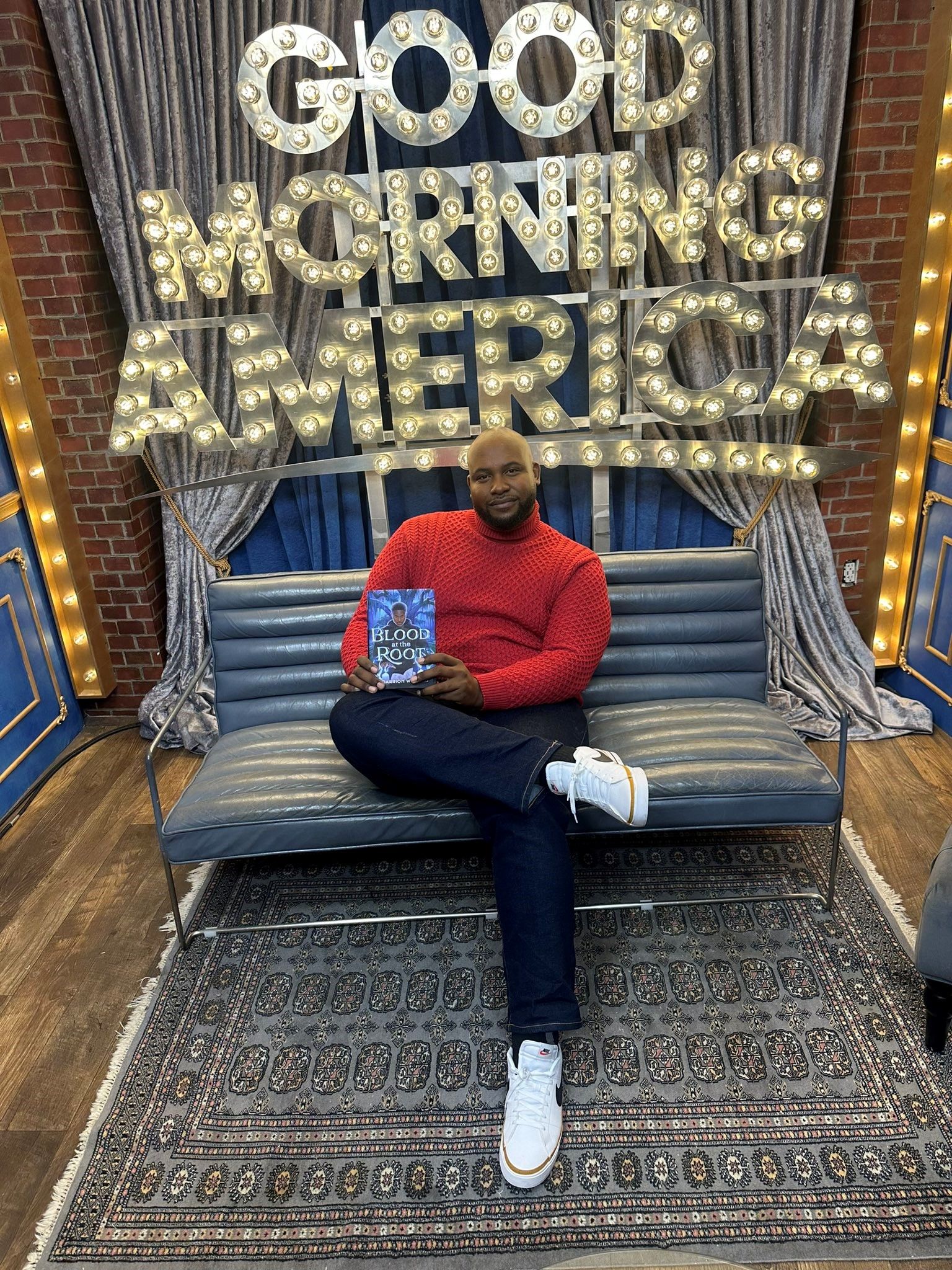

On May 7th, Blood at the Root was released by Labyrinth Road—an instant New York Times Bestseller.

On May 16th, LaDarrion posts his first TV appearance—on Good Morning America—on Instagram, adding it to the range of magical moments he recently experienced.

It seems that the universe has finally decided to reward LaDarrion for his persistence. When I ask if he’s religious, he says, “I believe in God. I don’t know if it’s in the Christian sense. I grew up in the Southern Baptist culture, and there’s some stuff I just don’t believe in anymore. But I believe that God and our ancestors—you know, our loved ones that have passed away—are guiding us.”

When things became too hard to bear, LaDarrion called out to the guides he relied on—not to beg for help, but to reason with them. “I had to challenge God,” he says. “I was like, ‘You said faith without works is dead. Well, I have faith, and I’ve done the work. I went through the storm. I went through everything You gave me, and I’ve survived and conquered. So, don’t You have to start making things happen?’”

Things did happen for LaDarrion, and he hasn’t taken them for granted. We spend quite some time talking about the importance of finding beauty in simplicity—or, rather, in things that many people believe to be simple, because they’ve never had to miss them.

LaDarrion tells me he regularly takes a moment to clean up his apartment and look around. “Then I’ll go, ‘Wow. I have a kitchen, a bathroom, and a living room. I can buy myself food, and I get to cook it.’ I try to do that, you know? Because there was a time when I spent my last money on my art and couldn’t eat for the next couple of days.”

The future looks bright for LaDarrion. He believes adversities might come again. But if they do, he’s convinced he'll bounce back. He recently finished writing his second book. At the time of this interview, a cover is in the works.

“Whatever happens, happens,” he says. “But I know I’ll still have my books. I’m going to produce more plays. Hopefully, I’ll make another short film. And I want to shoot my own feature one day.”

He’s come a long way from wielding an invisible wand in his living room in the town of Helena, dreaming of a different life. When people now try to push him into the background or pigeonhole him based on preconceived notions about race, he no longer has to sit there and take it. He built something tangible; something that is his. And he’s done it without getting a head start—in the solitude of the artist’s mind, relying on a vision he could only share with others many years later.

Looking back, I ask, what would he tell the toddler and teenage versions of himself?

His face softens. After mulling it over, he says, “To the 17-year-old, I’d say, ‘It’s going to get rough. I can’t sugarcoat it for you, man. But the resilience that’s growing inside of you right now—that love, that childlike innocence—never lose it. Keep tapping into whatever resilient spirit you have, because you’re going to need it.’”

And what about five-year-old LaDarrion? What wisdom would he impart on him?

“I’d tell him, ‘Just keep singing. Keep re-enacting those little movie scenes that you find really fun. It’s okay. Even if you have to take the remote control and create your own concert, it’s okay. Don’t be ashamed of it.’”

As he contemplates his words, his eyes momentarily fill with concern. More than once, these boys will desperately need their own Malik, but 31-year-old LaDarrion knows they’ll have to make do without the hero whose creation they’ll inspire one day.

He nods pensively.

“Yeah,” he says. “Yeah ... that’s what I would tell them.”

*Feature Photo: LaDarrion Williams producing his own play at MOments Playhouse in Hollywood.