More Rambling Conversations with Multi-Hyphenate Dan Mirvish: HBO, a Fictional Pundit, and Advice All Artists Need

Yes, Dan Mirvish is the ultimate hyphenate. Writer-Director-Author-Film Festival Creator-Author-Consummate Baker. Just ask the writers on the picket line that day, who devoured his delicious treats. Within a few weeks, word of his culinary skills had even migrated down to expanding picket lines at Manhattan Beach Studios, where one particular aficionado raved about them weeks later, as if they could still taste them on their tongue.

Part 1 of our interview ended in a hot tub. So, let's keep the party going ...

The HBO Deal

Scott Tobis (ST): Any TV or film projects that didn't come to fruition? You had mentioned something about an HBO deal a while back.

Dan Mirvish (DM): We had the Marty Eisenstaedt project. Ashton Kutcher’s company was going to produce. They had a first-look deal with CBS Studios and loved it. They were going to come on board, then we're all going to pitch it to Showtime. Then suddenly it all went poof and disappeared. Ten years later, it occurred to us that the whole thing with the writers and packaging fees might have been what sunk that project. We were ICM. The showrunners were at CAA. There could have been all these successive packaging fees, and we wouldn't have even known. We’ll never know what really happened.

ST: Have you thought about revisiting the character? (Author’s note: Eisenstadt was a fictional pundit that Dan and his partner Eitan Gorlin created that took credit for being the infamous anonymous source who told the media Sarah Palin didn't know that Africa was a continent. The story got picked up by AP, Washington Post, ABC News, CNN, NPR, the BBC, and newspapers in every country in the world.)

DM: Eitan and I wonder what would Marty have done in the Trump administration. What is he doing post Trump? We’ve given a lot of thought to why our book hasn’t been banned in Florida schools. That's a little offensive. That book should be banned by all kinds of people. I don't know why it hasn't been.

ST: And the infamous HBO deal?

DM: I had a meeting at HBO once to pitch myself as a director. The guy there just started laughing at me, saying, 'There's no WAY we'd hire you to direct a show. All the showrunners hire their best friends to direct.' As I dejectedly walked to the parking garage, the valet asked me how much I wanted for my 12-year-old Mazda minivan. He was looking for a used van. I still needed it, so I politely declined. I came home and told my wife, 'Good news! HBO made me an offer ... on the minivan.' In retrospect, I should have taken it.

ST: Okay. Less rambling and more focus. I’m going to try to go in chronological order.

DM: Good luck with that.

ST: I want to start with your third film, Between Us. What was the genesis of that.

DM: There was some chatter that The Weinstein Company had some interest in turning Open House into a stage play. So, I took a few trips to New York to meet with theater folk.

I asked the agents if they had any plays—not necessarily musicals—but plays that would make good film adaptations. They handed me stacks and stacks of Broadway and off-Broadway plays, because nobody ever asks for them. Usually those plays wind up being writing samples for the playwrights to get TV work in Hollywood, because that's where the money is for the agents. I read like thirty plays. Two of them seemed doable and a good match for me. One was a political thriller set during the Iowa primaries, about an aide who worked for an Iowa Senator. And I thought it was great. But it just seemed a little too big for what I thought I could do.

ST: Was that Ides of March? (The play was written by Beau Willimon, who went on to create the U.S. version of House of Cards, among other projects.)

DM: Yes. The one that George Clooney did. So, he got a happy ending for my sloppy seconds.

To be fair, if I had made it, I wouldn't have had Clooney, Ryan Gosling, and Phillip Seymour Hoffman, nor Leonardo DiCaprio producing it. It would have been me producing it, and you acting in it, so it all worked out fine. Years later, I met Beau Willimon, because I hadn't met him at the time And we laughed about it. Or he laughed at me. Anyway, there was laughter involved. Let's put it that way.

Anyway, the other play was Between Us, which was a four-hander. Two couples yelling and throwing things at each other, set in a house and an apartment. I got together with the playwright, Joe Hortua. He was excited to turn it into a feature.

It had been a hit off-Broadway play. I say 'hit' because I told people it was a hit off-Broadway play. It had a solid six-week run there, which is a hit as far as I'm concerned. So, Joe and I got together, and we wrote the film adaptation. We were going to make it in 2008. When was the financial crisis?

ST: 2007. 2008.

DM: We were all set to make it. We were going to do it for $3.1 million as a big indie film. We’re meeting agents and producers and casting directors and actors, and then the financial crisis hit, and there was no way you could do a film at any budget level. Everything kind of shut down for a while. That coincided with the Eisenstaedt book. So, when presented with the option of not getting paid to not direct a movie, or getting paid to write a book, your wife tells you to write a book. So we kind of put Between Us on hold for a couple of years. I did the book project and when we finally came back to it, we said, “It’s four people in two rooms. Why don't we make it on a micro-budget level?

ST: What year was that?

DM: IMDb says 2012 is when it was released, so probably 2010, 2011.

Ultra-low budget is actually what it’s called in the SAG contract. But it's micro, and some people say ultra-low is what the last three films of mine have been.

ST: Really? They’re good looking films.

DM: The nice thing is because we'd already been talking to agents and actors two years earlier, we could go back to those same people and say the script is exactly the same. The budget’s different, but the script is the same. We literally didn't change a word of it. The only difference is that we all would have gotten paid more. So, that allowed us to wind up ultimately getting, you know, Taye Diggs, Julia Stiles, Melissa George, and David Harbour in the film, which was a pretty good cast. (Note: Harbour originated the role in the “hit” off-Broadway production.)

Between Us: Two couples reunite over two incendiary evenings where anything can happen in this darkly comedic story of best friends, marriage, love, disappointment, and dreams.

ST: Who was the first actor attached?

DM: Taye Diggs. We thought we had Kerry Washington and America Ferrara attached. Taye was like, ‘That sounds like a great cast to be with.’ Then they all dropped out. But Taye stuck with it. God bless him. That was a real solid. Then we built the cast back up around him. Who wouldn't want to be in a movie with him?

ST: I remember stories about neighbors coming to the house when you were shooting it here because of his presence.

DM: Yeah, Debbie is still swooning over him today. Taye became the anchor.

ST: Tell me about Julia Stiles.

DM: The way we got Julia is a good story. I had been interviewing a number of actresses. We had some really good options—famous people and good actresses. I was meeting with one, and in the middle, I get a call from (Julia’s) agent who said, 'Oh, I forgot about her. What do you think? Julia Stiles.' Because that's how agents talk about women. It’s funny, when she asked her manager about the project, he remembered me, 'Yeah. Dan drove me around his minivan in Venice two years ago, because my car was in the shop.' These things have a funny way of paying off.

We had already asked about her availability and had been told she was rehearsing a Broadway play and unavailable. Neil Labute’s first Broadway play. The agent says, 'The financing fell through two hours ago. She's completely distraught. We don't know what to do with her until the next Bourne movie.' Hollywood doesn't work that fast. The next Bourne movie's in four months or something like that. So I said, send her the script. Twenty-four hours later, I was on the phone with her. Two weeks later, she was in this very kitchen rehearsing. We were doing the trick of finding actors at their most vulnerable emotional moment. Then you swoop in, and you save them.

ST: You must have been relieved to get her.

DM: Yes, but we had good backups. There were definitely actresses we could have chosen that would have been good for the film. But she was a bigger name and is a great actress. She was happy to do it.

Melissa George was very last minute. I didn't meet her until she showed up for rehearsal. We were just an offer. She was traveling, and this was before Zoom, so the first time I met her was when she walked into this house. She's so good in the film, and I got along great with her.

ST: Rehearsing for two weeks sounds like a luxury, especially for an indie.

DM: It was. For the first week, we had the cast (at this house). Then we moved on to the hotel in Hollywood where we put the actors up. We were using it as the location, and they also wanted our actors to stay there. So they gave us an amazing deal. We were shooting there because it was converted apartments.

All the interior New York apartment stuff was shot at the hotel. Then the Midwestern house was just like a quarter mile away. A couple of weeks later, I went to Nebraska and shot all the exterior driving scenes for the Midwestern house. From there, I went to New York, and we shot a full day with Julia. Just her crossing the street, and going to the flower shop, and basically the New York City exteriors.

ST: You wound up with a great cast, rehearsal time, and locations. All for an ultra-low budget film. Did you appreciate your fortune at the time?

DM: Yes. But I think all of us knew this was based on a play with good, meaty material.

ST: Do you always get that much rehearsal time?

DM: On Bernard and Huey, we did three or four days of rehearsal. And that seemed optimal. If you rehearse the scene two weeks before you start shooting, it may be five weeks until you actually shoot that scene. So, having all that rehearsal time may not do you that much good. You reach a point of diminishing returns after about three or four days of it.

ST: Tell me about your former ADU (a lovely garage with a green screen) filling in as a New York City subway car.

DM: That was Bernard and Huey. All the films that we've shot had something in there. On Between Us, we shot a day there. There are flashbacks of Melissa George's character having an affair with a Brazilian painter. Her husband at the time played the painter because he was in town anyway. His grandmother's Brazilian, although he's from Chile, I believe. Am I rambling?

ST: It’s okay. I pitched it that way. The readers have been given advance warning.

DM: We shot Between Us for about $200,000. We started shooting with $60K in the bank. We didn't get most of the budget until like the third to the last day of shooting, which is cutting it a little close. It was a bit of a teaching set. There were a lot of AFI students on set. My cinematographer, Nancy Schreiber, had been teaching classes at AFI. So she brought in a bunch of her students, but she also would every now and again bring in a ringer—one of her ASC friends as a second operator—just for fun. We were all calling in favors, left and right. But, in the end, everybody got paid, so that was good. They didn't get paid much, but they got paid a little bit. It was tough because it was a two camera shoot. We used the RED camera.

ST: Interesting. What's the infamous quote? Directing is selecting when you're using digital.

DM: Yeah, Scorsese said that. Did you hear that from me? Because I quote that all the time, but it's his quote. Yeah, that's exactly right. I mean, there are times when it makes sense, and there are times it doesn't make sense, and there are times where it could go either way, and you know, it depends on the situation. And it worked on Between Us, but it had challenges.

You need twice as many people with twice as many cables. You're lighting the scene, not lighting for the shot. Things like that. And so the irony is you think you're gonna get twice as much coverage. But now having done two films (Open House was also two cameras, but they were little handheld mini DV cameras), it's like a TV shoot really, you know?

The last two films (Bernard and 18 1/2) were one-camera shoots, I would stick with one camera, and for the most part, I think it would depend a little bit on the movie. I think you just have more control over any given shot—improvisation where you want to get a catch with a second camera.

ST: Do you have a favorite or treasured child of your five films?

DM: Probably 18 1/2 just because it's the most recent, but I think everything kind of came together—acting, cinematography. Personality wise, people got along pretty well, which has not always happened. But there was a global pandemic in the middle of it.

ST: How do you handle distribution of your films? I seem to recall that you have a unique approach.

DM: For Between Us, domestic was through a company called Monterey Media. And we had a 50 city theatrical release. It wound up on Netflix, Showtime, and Starz. All three at different times, you know? Then internationally, there was another company that sold to 145 countries, including North Korea. The investors made back about a third of their money, which is good for these things. It's still out there. I mean, it's still streaming, but you don't get a penny for that.

ST: And North Korea ...

DM: A foreign sales company sold a group a slate of ten films, which ours was one. Ava DuVernay’s first film was one of the other ones. They sold it to a Chinese distributor, and Chinese distributors include North Korea in their suite of territories. Because I was dealing directly with the payroll company, I had to physically see the contracts for all the sales deals. I was like, 'Oh my god, we sold North Korea!' I called Ava and told her. She had no idea.

ST: You’re very hands on, so I assume you’re involved with the marketing of your films.

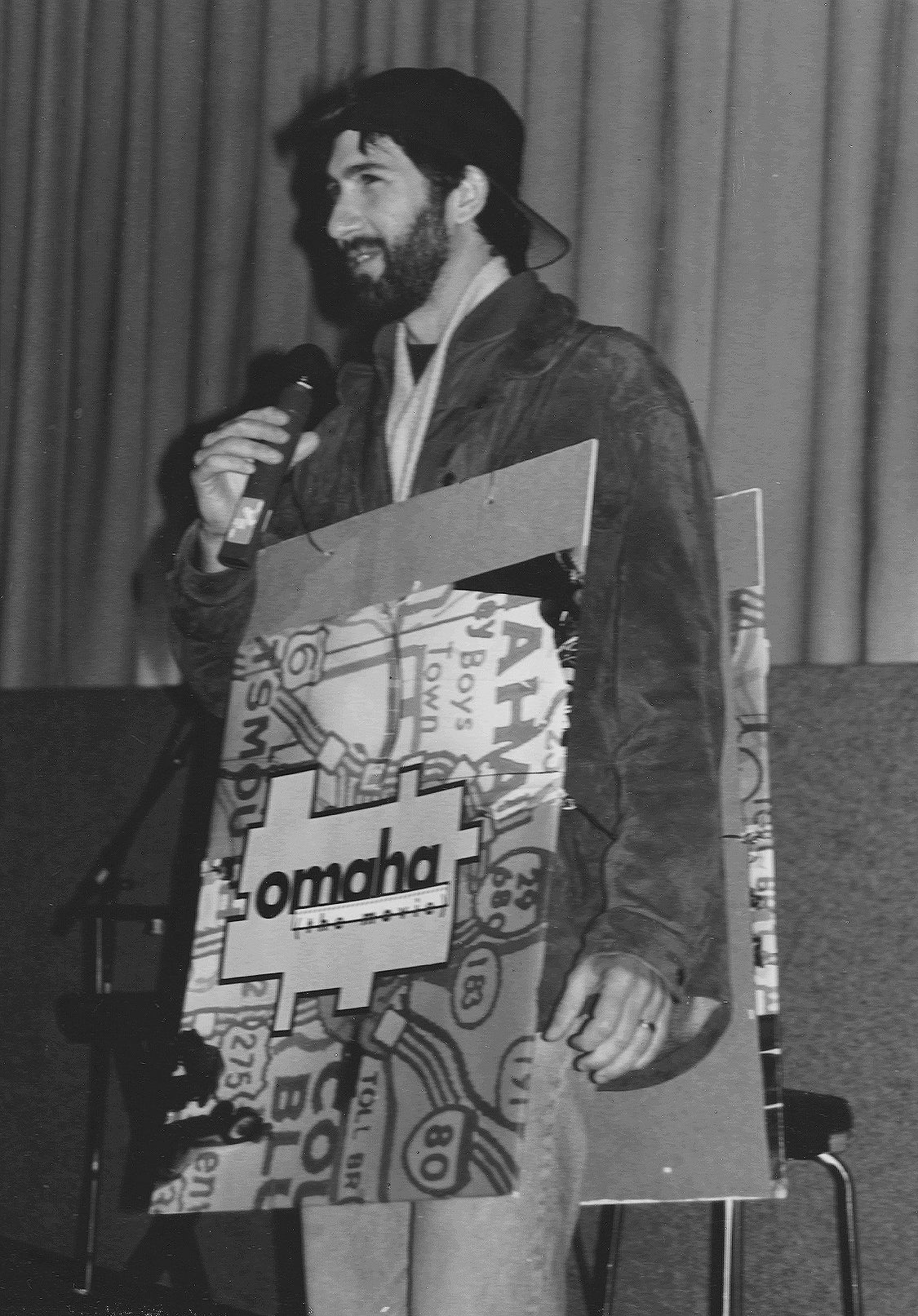

DM: Oh, yeah, I did a screening for Omaha (The Movie), where I threw raw steak—Omaha Steaks, obviously. I threw corn on the cob at the audience at our premiere, which was cheaper than throwing meat at the audience. I learned that the hard way. You know, throwing raw steak at the audience got me on KTLA evening news.

ST: Our readers will need to know, what was the thought process behind that particular move? Throwing steak at the audience? Was that a P.T. Barnum thing?

DM: I mean, it seemed obvious to me. We had done a little product placement with Omaha. If we did throw Omaha Steaks at the audience, that would have been really expensive. I just went to the market and bought steak wrapped in plastic. I've done stuff like that. I've worn a sandwich board at almost every screening of every film. On 18 1/2, we had mysterious Nixon* protesters. I’ll do whatever it takes. (*Note: As a reminder to those slightly lost amidst the rambling, 18 1/2 is a Watergate film.)

We had our world premiere at the Woodstock Film Festival, which was a week after the New York Film Festival, Paul Verhoeven was premiering Benedetta, his lesbian nun film, and there were mysterious protesters from some obscure Catholic sect saying that this lesbian nun movie is blasphemy. He got a lot of press and attention for that. So I wondered if we'll get protesters at Woodstock, and sure enough, we did. Go figure, you know.

ST: Let’s back up and little discuss Bernard and Huey. It has quite a pedigree as it’s based on an original screenplay by Pulitzer Prize-winner Jules Feiffer.

DM: You’re part of the story here. Carnal Knowledge had been an influence on Between Us in the script stages. (Co-writer) Joe Hortua was a big fan, as it was essentially a ‘two couples yelling and throwing things at each other’ kind of movie. Mike Nichols directed in 1971, and it was written by Jules Feiffer. It had been a reference point for us, and my cinematographer, Nancy. We sort of stole from Carnal for the cover of our pitchbook for Between Us. I think I was in post production with the film, which of course, we were editing here in the house—not just the garage, but in the actual kitchen, where you are sitting. The magic happened right there. My buddy, Dean Gonzales, was the editor for most of it.

Anyway, we were editing, and I was reading an article, and I said, 'I wonder what happened to Jules Feiffer.' I knew he was a cartoonist for The Village Voice for 44 years, as well as a Pulitzer Prize winner, so I was familiar with his work, but I was curious and found a recent interview with him. It said he was working as a graphic novelist, teaching and living in the Hamptons. And then at the end of the article, it mentioned that he had several unproduced screenplays.

I watch what I imagine the 10-year-old Daniel Mirvish looked like when he stumbled across a plate of freshly baked chocolate chip cookies. Crossed with the thunderstruck look of Michael Corleone when he sees his future bride in Italy.

DM: I thought, Carnal Knowledge, Popeye. He’d worked with Altman. He wrote Little Murders, which Alan Arkin directed. That’s a pretty good group. Mike Nichols. Altman, Alan Arkin. So, I sent him an email. He had been friends with Altman. Altman had recently passed away. Altman's widow, Katherine, was still alive then, and she sent her greetings to him, and my old producer, Dana Altman, had worked on Popeye when he was, like, 14, because Dana's little brother was Sweet Pea.

He said, 'Yeah, I think I got some stuff. But I've been divorced so many times, and everything's in storage. I don't know where anything is, so call me back in three months.' I contacted him again three months later. 'I still don't know where anything is. Get back in another three months.' And I kept doing this, pestering him for like, a year and a half. Meanwhile, I had met one of his daughters who had a film with Slamdance, Halley Feiffer, but she didn't know anything about the screenplays either.

But it was nice, and that kind of kept the conversation [with Jules] going. Then my friend Kevin said, 'Oh, I think I remember reading one of the screenplays in Scenario magazine back in the 90s.'

And I said 'Well, do you still have your old copies of the magazine?'

'No, I just got divorced. Everything's in storage. I don't know where anything is.'

And then I ran into you at the Chinese restaurant over there ... and you said the exact same thing about the magazine, 'I have all the copies of Scenario.'

'Where are they??'

'Oh, I just got divorced and they’re in storage.'

In the end, both of my divorced friends were useless, so I tracked down one of the only two libraries in America that still had copies. The Academy Library on La Cienega. So I went there.

We take a little detour as I admire the heat lamp over Dan’s stove. I’ve never seen one outside of a restaurant. Its very cool and very useful. Dan walks the walk on the set and in his home.

DM: At The Academy Library, I read the script. It’s Bernard and Huey. I call Jules. I didn't even know the title we were looking for. He said it was formatted differently for the magazine. So it was a little hard to tell if it was the whole script, or had been abridged when it was published. He didn’t remember anything beyond that his assistant had sent it in. 'She may have abridged it a little bit, I don't know.'

It was based on these characters that he created in 1957 in The Village Voice. Then in the early 80s, he brought them back as these middle-aged guys for a regular monthly strip in the back of Playboy. Because he was buddies with Hugh Hefner.

Showtime commissioned him to write the screenplay in 1986, but the week he turned it in, they changed ownership and became a sort of 'let's do boxing instead of movies.' They never paid him for the script. His producing partner tried to get it made as an independent film, but they didn't have any luck with it. And then it disappeared.

The next time it appears is when it shows up in Scenario magazine in the early 90s.

I said, 'Let's ask your assistant if she has a floppy disk.'

And he goes, 'No, she's dead.'

'I'm sorry for your loss. Um, what about your agent? You have a big Hollywood agent, and they probably have a copy of the script.'

'No, he’s dead.'

'What about your lawyer?'

'Dead, too.'

The article had mentioned a producing partner named Michael Brandman. But they spelled his name wrong, because I tried to look them up and couldn't find him. And then Feiffer remembered how to spell his name. I was able to track him down, and thank God, he was still alive, living in Hollywood, was still married, and still had his archives. He had a printed copy and was a super sweet guy.

The version in the magazine wasn’t abridged. But we didn't know at the time. We had to make sure. We kept doing research on it and discovered that Jules had donated his archives—the reason he didn't have his old scripts—to the Library of Congress about ten years earlier and kind of forgotten about.

I sent a buddy in DC to the Library of Congress, and we found the original handwritten draft of the script, with little doodles and his plumber's phone number in the margin.

Jules says, 'I'm 87. When are we making this fucking movie?'

It still took a long time, we then had to do research with all these entities like Playboy, Showtime, and The Village Voice to make sure Jules really had the rights.

It took about another year and a half just to figure out the rights. And then, since Jules is a WGA member, we had to then deal with the WGA contract. Of course, Jules doesn't have a lawyer or an agent anymore, so we were using his book agent. She was good, but she's not super familiar with film contracts. So it took a while to get the contract finalized.

ST: What do you think the time frame was from getting the copy of the magazine with the script to getting the rights solidified?

DM: It took about a year and a half to find the right script. Then another year and a half to clarify all the rights and contracts. Meanwhile, the whole time, I didn't know if the script would be any good. When you hear that something was an unproduced screenplay, maybe there's a reason why it was an unproduced screenplay. Maybe it was no good. Maybe the rights were tied up somewhere.

But I looked at it this way, I was having fun every time I would meet with Jules. I went out to the Hamptons a few times, and I'd always film him out there—and use it for our Kickstarter campaign. He was an inveterate talker and knew everyone in the film/theater/comics world—he was buddies with Stan Lee, Hugh Hefner, and Philip Roth! He was originally supposed to write Dr. Strangelove. But Kubrick didn't like his take on it.

ST: When did you begin production on the Feiffer script?

DM: We shot it in 2016. Our last day of shooting was the day that Trump got elected. That's how I can remember, and then it came out in 2017.

ST: Our readers would love some insight into the casting process.

DM: That took a while. We got David Koechner (Anchorman and many other films) first. And then kind of stumbled into Jim Rash.

I was “dialing for dollars” trying to raise money for the film. I had this big list of production companies, and I called this assistant, ‘Hey, we're making this film called Bernard and Huey.' He tells me that he’s read it, since they’re also a management company. He mentioned that he thought Jim Rash would be great as Bernard. I thought to myself: 'Oscar winner*, Jim Rash, would look great on a poster.' (*Note: Jim won an Academy Award for co-writing Alexander Payne’s The Descendants.)

My casting director hadn't thought of him, but I thought it was an interesting idea. He was great to work with, and he's great in the movie. He and Koechner had great chemistry, and they really kind of looked like Bernard and Huey (from the original comics). At one point, Koechner told me he signed because we were out to Don Cheadle for Bernard. I told him that we hadn’t heard back from him. To this day, we still haven't heard back from Cheadle. So if anyone out there knows him …

Dan laughs at his own joke. Oddly, this is endearing, unlike the way I find most self-laughter to be mildly (or painfully) annoying. Perhaps it’s a Nebraska thing, or maybe it’s years of telling these kind of anecdotes to investors, actors, distribution companies, airlines, etc. Either way, it doesn’t sound practiced or rehearsed. I suspect it’s part of his appeal. Dan almost always comes across as genuine. Perhaps only his wife knows the truth.

Koechner came up through Second City and Upright Citizens Brigade and did a season on SNL. Jim Rash came out of The Groundlings. It was interesting, since they never met each other before but had these weird Venn Diagrams of comedy elite and improv elite.

We had three or four days of rehearsal with each other, but it was strange. Nancy Travis' character is never in a scene with Richard Kind, but during rehearsal time, they would overlap. People would come to do a costume fitting, and we had food. I had two interns making grilled veggies and hummus and all kinds of different things because actors don't eat. I mean, it's axiomatic. They don't eat carbs, but they really don't eat much. So that would feed them over the course of a whole day.

ST: Was there any issue because you had an Oscar-winning screenwriter in the cast—in terms of line changes?

DM: When we had script issues, Jim would offer suggestions, and I’d welcome them. I'm like, Yes, Oscar winner, you know? Because you play with the script that you have. That was the interesting thing working with Feiffer. The film was set in 1986, with flashbacks to 1961. And the first conversation I had with Jules was about being hard enough to do a period film on a low budget. I don't think I can do two periods. Do you mind if we move everything up 30 years; then the flashbacks would be 1986. Feiffer was around 50 when he wrote the script and was thinking back to his college days. It then became about the same age that I was, and about the same age that Jim and David were—which meant that the sort of cultural references and touchstones to the flashbacks were punk references, instead of jazz (as in the original script).

So it was mostly me, but in consultation with Jules, but what was surprising to all of us was how little had to change. The one thing that did change was that in the original, the daughter character wanted to be an aspiring cartoonist for The Village Voice. So I said, why don't we change it to a graphic novelist, because if you're a cartoonist now, that's the hot thing.

ST: Do you have a songwriting credit on the movie?

DM: Yeah, I didn't want to pay for the rights to some of the songs, something like that. So it's an old song I wrote in college as well. It got me into ASCAP. Yeah.

ST: Did you contemplate asking for a writing credit on the updated screenplay?

DM: The script is Feiffer's with a few tweaks from me. It’s his personality. It’s funny because Feiffer is living in the Hamptons, and we were shooting almost all of it in L.A. On our first day of production, the actors were asking if Jules wouldn’t mind if we change this line or that. On the first day of production, right before we got the first shot off, I called him on my cell phone, and I had Jim and David there with me. And the first thing Jules says is, 'What, you haven't shot this thing yet?'

It just cracked me up. I said, 'By the way, you know, we've got Jim and David here, and they both have great improv backgrounds. Do you mind if we did a little improv?'

'No, that's fine.' It turns out Feiffer actually had a history as his first experience in theater was at Second City in Chicago. Mike Nichols and Elaine May. Since both Koechner and (fellow cast member) Richard Kind came out of Second City, he gave his blessing.

Feiffer loves the film. He saw it a couple of times.

ST: I keep meaning to ask this question, one that I suspect a number of indie filmmakers would like to know. With the kind of low-budget films you make, how do you budget for rehearsal time? That seems like a luxury most filmmakers working on that scale can’t afford.

DM: Well, the secret is you don't call it rehearsal. Call it a “get together” at the director's house, or a costume fitting, with lunch … at the director's house.

ST: Okay, Dan, we need to start wrapping up. If this was a movie theater, 90% of the audience would have walked out already. Same with our readers, although I suspect they realized they should have taken the ‘rambling interview’ aspect of the title more seriously …

You’re a producer, director, and writer on your films. How do you maintain your sanity juggling all the different things you need to do on each project?

DM: Here's the best new advice that I've heard. And it's not mine. It's from the late Monte Hellman, the director of Two-Lane Blacktop. His producing partner told me this line that Monte used to say, which is that … let me see if I can get it right.

‘If you make a film for money, and it fails, you've lost your money. If you make a film for art and it doesn't make any money, you still have your art.’

It went something like that. The point is if you approach these films with that attitude, it changes everything. It changes why you're doing it, why people are giving you money, why they're not giving you money, and what kind of distribution or festival play you want.

It’s not about making money. It’s about getting the film seen.

Film is like a tree in the forest. If nobody sees it, it doesn't really exist. You could have a film that goes straight to Netflix. And if nobody knows about it, does it exist? That's got to do with the streamers and the numbers, since they're not reporting numbers. Even if you know the numbers, you don't have any real engagement with the audience. There’s no Q&A's, there's no comments, there's none of those things that you get in a real theatrical release. Even if you have a theatrical release in 3,600 screens across the country, you can physically only go to a couple of them at a weekend.

With 18 ½, we were in 60 cities, and it lasted over seven months. I could travel almost every weekend to various cities. In the post-pandemic environment, getting any screens was next to impossible. That was an accomplishment, but also meant that we could engage with the audience, plus the 25 festivals on four continents.

ST: I love that. Do you separate the creation, development and production of the film from the marketing thing? Except in your mindset? Do you find a healthy balance for the two sides of the equation?

DM: It’s a good question, because I've just figured it out recently. Why do I spend years prepping and developing a movie? Finding the script and raising the money and all the pre-production and then you spend all of three weeks on set. Then it's another 5-20 years with time off for good behavior when you're done with the film. Can you still call yourself a director? If you've only directed three weeks out of that whole time? What do I have to show for this thing? After all this, I have 88 minutes of film. But then I look at the behind the scenes footage, and it's two hours long—on top of the 88 minutes. So, it occurred to me that really what I'm doing is creating five-year long, community-based art projects. Yeah, write that one down. And this is an exclusive.

I don’t just make films. I am creating five-year long, community-based art projects.

So, if you look at it in that context, then everything makes sense. From pre-production to post-production. You have 300 backers that started you in pre-production—doing the social media, the crowdfunding. We made these people into my writing/producing partner. Daniel (Moya) put it well. He didn't realize at the time when we were doing the Seed & Spark campaign on 18 1/2.

Dan also didn't realize a lot of the goofy things I was doing, like photoshopping investor’s faces into the famous picture of Elvis and Nixon. It was great, because then people would share that on their social media. And then more people are like, 'Oh, that's cool. Where'd you get that from?'

'Oh, I gave money to the filmmaker.'

'Cool. I'll do that too.'

We put their names into audio of the Nixon tapes, and Nixon would say their names. It was goofy, but people loved it.

What Daniel said, which hadn't occurred to me, was that all that stuff kind of helped set the tone for the kinds of humor and what it would be like on set and how we would edit the film.

Even yesterday, I was sending things like that. When I see it’s the birthday of one of my backers, I take a picture of Nixon with a birthday cake. And I’ll write ‘Happy birthday, Scott.’ They're still putting it up on their Facebook pages. The backers become emotionally invested when I do this kind of thing. I send updates, religiously, like once a month or something. Been a couple of months.

ST: How did you arrange financing “back in the day” for these smaller projects? Before Kickstarter and other crowdfunding websites existed?

DM: They kind of did. We just didn't call it that. What was crowdfunding before the internet? It was different, but it was still the same. I would reach out to friends and family in person, or meet some rich guy and then they would say, 'No, but go visit my venture capital buddy Chuck,' and you go visit that person.

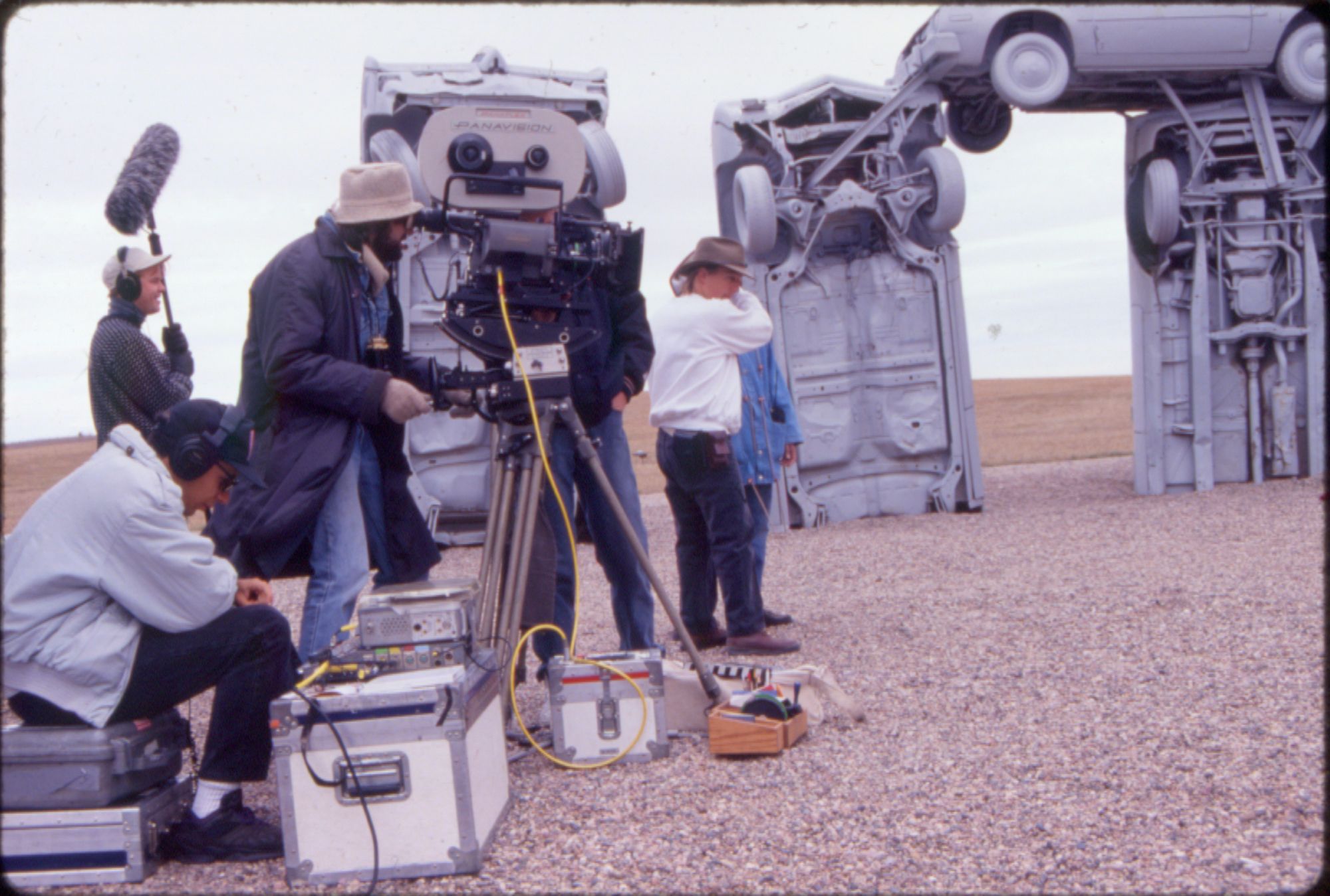

The budget for Omaha (The Movie) was officially $38,000. Unofficially, we say $87,000. A little more, because there was a whole insurance thing that happened, (where) the lab ruined some of our footage. But we had insurance. So, we were able to get like $40,000 or something more than the budget of the film to reshoot a couple of scenes, but it meant that we had to go back to Carhenge. I don't have to tell you what a big deal that is.

ST: It feels like you found a way to remain sane while undergoing this long process between each film.

DM: Yeah, it definitely took some persistence, but also realizing that the journey was part of the fun of it, too. Even if nothing ever happened, I still would have had this great relationship with Jules Feiffer. Like he said, you're building, although maybe it's not a specific word Feiffer likes, but you're getting to hang with a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer and cartoonist whose worked with (Academy Award-winner) Mike Nichols and with everyone. So, that's kind of how I look at all these things. Is this journey worthwhile in and of itself? Even if nothing else happens …

ST: One final question in a long line of final questions I’ve asked as part of the all-too-literal rambling conversation. What are you working on at the moment?

DM: I’m prepping for the DVD release of 18½, which is coming out in April, 2024. I'm also planning on re-scanning the negative for my first film, Omaha (The Movie). And here's a scoop!—we're planning a graphic novel version of my unproduced screenplay Stamp & Deliver with my illustrator buddy Matthew Fuller. See, you've got to be media agnostic.

Parting Words

I asked Dan if he wanted to offer any last minute advice for filmmakers. Here is his unedited response, including a few things already addressed in the preceding pages.

Number one: Marry well.

Screenwriters: Be clear on who you're writing for before you start (applies mainly to features, but probably pilots, too). Is it a big-budget spec? Is it a low-budget indie you or your friends are going to make? Is it just intended as a writing sample? Or just a passion project written for practice? Any of which are fine, but each comes with their own sets of structures, formats and emphases, so it's good to know going in so you have the right level of expectation coming out.

Directors: Try to be media agnostic, generate your own material (either write it yourself or collaborate with writers), learn every facet of the filmmaking process (at some point you'll have to do them all, or at very least, know enough to hire and supervise the right people). Of all subspecialties, knowing editing is the most important (because usually on any given set, there's plenty of people around who know cinematography, but no one focusing on editing and coverage decisions except the director).

Picketers: Wear sunscreen, be chatty but not pitchy, and go early for fresher donuts. (Having worked in a donut store, I can tell you even if donuts are delivered in the afternoon, chances are they were made in the morning.)

The Secret of the Scones

Dan felt that it wouldn’t be fair to leave the reader without passing along his mother’s fantastic recipe for the world renowned (or at least Westside picket line renowned) blueberry scone recipe.

2 cups flour

1 tablespoon baking powder

3 tablespoons sugar

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon cinnamon

Just a hint of cardamom

6 tablespoons butter

1 egg

1 teaspoon vanilla

1/2 cup of milk

1 cup of blueberries

1/4 cup powdered sugar

Preheat oven to 425F. Combine dry ingredients. Cut in butter until mixture resembles coarse crumbs. Mix in wet ingredients. Add blueberries. Plop 12 about 1/3 cupfuls onto baking sheet (I like to use a silpat—cleans up faster). Bake for about 13 minutes (until just a few of the blueberries are bursting). Sprinkle on powdered sugar. Bring to picket line while hot.

(Recipe courtesy of Lynda Mirvish)

If readers want to learn more about Dan, apart from his culinary skills, check out his book, The Cheerful Subversive’s Guide to Independent Filmmaking, as well as his website and listen to his interview on Pipeline's OG podcast, "Reckless Creatives."

To get a small taste of how very different Slamdance is from other film festivals, here’s a peek their annual Hot Tub Summit video, a unique event which has been happening for almost twenty years ...

*Feature Photo: Dan Mirvish (photo by Michael Dumler)