"The Last of Us, Part II" - An Analysis of Perspective in Storytelling

WARNING: This article contains MAJOR plot spoilers for both "The Last of Us" and "The Last of Us, Part II" video games. It also contains valuable insights and lessons for writers who want to make their characters deeper, less tropey, and more fascinating overall for their readers.

The choice to continue is yours ...

Hey everybody. Today, I have an announcement to make:

I love Neil Druckmann.

There, I said it.

Too personal? It is a bit weird, I’ll admit. Especially given that I’ve never met the man, and he definitely doesn’t know who I am. God, I feel like a 12-year-old girl with posters covering the walls of my room ...

Allow me to clarify: I love Neil Druckmann’s work. Specifically regarding "The Last of Us" video game series.

Fully. Completely. With all my heart.

Today, I beat Part II of this franchise. And I did not expect to feel the way I feel right now. My heart raced. My skin crawled. I was morally and ethically unsure of where I stood more times than I could count.

And it wasn’t because I had to brutally kill zombified humans to survive.

It was because of the character work. The lengths that this series goes to in order to make me care about everyone involved went beyond my wildest imagination. I’m honestly not sure I can look at violent games the same way ever again ...

I’m not kidding when I say that these games taught me a valuable lesson about the importance of perspective and POV in storytelling … actually, the lessons go much further than that. This game may have changed my outlook on life.

Think I’m being hyperbolic? Allow me to explain for those who are unfamiliar.

SPOILERS START NOW … YOU’VE BEEN WARNED.

This award-winning franchise takes place in a future America where some sort of virus has broken out that turns people into violent killing machines. Part I begins with a 40-something father named Joel as he tries to keep his daughter safe on outbreak day.

He fails. She dies in his arms while he begs her to come back to life. Within the first ten minutes, your heart is already breaking.

Flash forward years later—the government has crumbled, failing to contain the spread of whatever the fuck disease this is. Humanity now operates as a fractured, mostly lawless state. Joel survives as a smuggler, evading patrols and getting things into and out of the city (Boston). And while he is still physically breathing, it’s clear that a big part of him died that day with Sarah (his daughter). He is the epitome of a broken man.

Insert Ellie.

Ellie is a 14-year old who Joel is tasked with smuggling. She claims to be “immune” to the effects of the virus; she got bit three weeks ago and hasn’t turned into a murderous rage machine. Obviously, this is something that requires further study. Joel’s job is to get her downtown where he’ll hand her off to a resistance group and get paid. They’ll take her the rest of the way to a working hospital (a rare thing in this universe) with doctors who might be able to create a vaccine from her blood. It’s a typical job for Joel—deliver cargo, get paid.

As any veteran storyteller has already guessed, clearly that doesn’t happen.

When he arrives at the rendezvous point, Joel finds the resistance group dead. If the world is going to be saved, he’s going to have to take Ellie much, much farther than downtown Boston.

And that’s exactly what he does.

Over the course of the next eight to ten hours of gameplay, you lead Joel and Ellie through dozens of dangerous situations. Past bandits who want to rob them, zombies who want to eat them, and cannibals who … also want to eat them. You watch as these two bond, and become like family. You watch as Joel slowly comes to accept Ellie as a capable person, not a kid who needs constant protecting. You watch Ellie take care of Joel in moments when he can’t even stand, and nurse him back to health after a brutal injury. And you watch Joel open up about the death of his daughter, and he lets Ellie fill that missing void in his heart.

I mean it when I say that I connected with these two more than just about any other character duo ever. In any medium. Game. Book. Graphic novel. Film. Etc.

By the end, I freaking loved Joel. And I freaking loved Ellie. I wanted good things to happen to them.

And then, we made it to the hospital.

Our intrepid heroes stumble upon the location they’ve been seeking all this time. The resistance group is here. There is a doctor on site. They can use Ellie to create a vaccine that will save all of mankind.

But they have to kill her to do it. Saving humanity means that someone I love has to die.

…

Fuck that.

That was my immediate reaction to this news (and it’s pretty much the same for every other person I’ve talked to who has played this game). I was NOT about to let that happen.

The last stage has Joel grab a gun and take out everyone in the goddamn ward. You shank, choke, and shoot through dozens of people in order to make it to the operating room, where you catch the doctor right as he’s about to cut open our little girl ...

You want to know what I did next?

I shot this physician right between the eyes. I shot him without a second thought. This decision was as easy for me as “I’m hungry, I’m going to make a sandwich.” I pulled the trigger with absolutely glee in my heart.

I (err… Joel) was making an objectively bad decision. It was the “wrong” choice for 99.99999% of people. I was doing something greedy … something selfish. And I didn’t fucking care.

From Joel’s perspective, the perspective I had been seeing things from for the last eight to ten hours, it wasn’t a choice. It was the ONLY choice. There was no other option in my mind.

I ran out of that hospital with Ellie in my arms and took her to safety, where we would live out the rest of our days in a blissful, happily ever after.

At least until the second game came out … (there’s a point to this, I promise—bear with me).

This one takes place years later, where Ellie is now fully grown. They live in a small town in Wyoming, and the game begins with both of them being sent out on separate patrols.

Ellie comes back.

Joel does not.

Ellie immediately starts searching. She finds him captured by a group of rogue hunters, led by a woman named Abby.

She’s forced to watch as Abby beats Joel’s head in with a golf club. She watches as her surrogate father bleeds out helplessly on the floor of a decrepit ski lodge.

The hunters leave Ellie alive.

I vowed revenge.

In no uncertain terms—It. Was. Fucking. On.

At this moment, I wanted nothing more than to kill Abby. To make her suffer the way she had made Joel suffer. For eight hours of game time, my goal was to locate this woman and end her life. Finding out why she had killed him was almost secondary. I didn’t really care. The why hardly mattered.

She needed to get got.

For three days I searched. I found all of Abby’s friends. I killed all of those friends. But Abby was nowhere to be found.

I was just about to give up … when Abby appears in Ellie’s hideout, a gun trained right at her. Finally, the moment I’ve been waiting for! I’m about to get revenge on Joel’s killer … vengeance for my surrogate father! My goal is within reach! My lust for violence will be fulfilled!!

And then … something happened. Something extremely profound and unexpected ...

The game cuts to black ...

And when we come back, we’re not with Ellie anymore ...

We switch perspectives.

We switch to Abby’s perspective. And we live out the last three days from her POV.

I did not like this decision at first glance. In fact, I hated it. I wanted nothing more than to jump back into Ellie’s life and kill this witch. I said so, out loud, multiple times as I navigated Abby’s world.

But damn if the game didn’t make me eat those words.

It doesn’t take long for us to discover something radically important to the story: Abby is the daughter of the doctor who was operating on Ellie in the first game. The doctor whose brains I splattered against the far wall. The doctor I gleefully shot without a second thought.

Seven years passed between the first game’s release and the sequel. When I killed that doctor, I only paid attention to what it would mean for me. I only cared about what I wanted. It never even crossed my mind to think about what that decision would mean for others. What ripple effects my actions would have …

That man had a family. He had a child. He had a child who I orphaned.

This revelation fucked me up.

But you know what fucked me up worse? The fact that the game made me keep playing as Abby. Not for one scene. Not for an hour ...

She become the viewpoint character for another eight hours. And while she has a dark past (just like Ellie and Joel), the more I played, the harder it was for me to say that I thought Abby was the “bad guy.”

Over the course of the three days that Ellie is seeking revenge, Abby goes through shit of her own. She’s a full and complete person in her own right. Her life is just as deep, complex, and intrinsically complicated as Ellie’s.

She collects quarters, and has a debilitating fear of heights. She sticks her neck out for friends who are in trouble. She helps a little trans boy escape persecution from a religious cult. She goes out of her way to help a woman who saved her life.

Abby has done bad things. But I couldn’t rightfully say that she was a bad person.

And the more I saw things from Abby’s perspective, the more I saw how she was entirely justified in killing Joel.

He’d singlehandedly dismantled the resistance group that was trying to rebuild America. He’d screwed humanity out of a cure for a virus that made everyone live in constant fear. He’d murdered her father in cold blood.

Abby wasn’t wrong.

She was truly the hero of her own freaking story.

In a parallel universe, I can absolutely see a version of this game where Abby is the “good guy,” getting vengeance for her murdered dad. She would be entirely justified in that pursuit.

Just like how when I was playing as Ellie, getting vengeance for her murdered dad seemed entirely justified.

I watched as Abby went to the ends of the earth to find medical supplies for a dying friend, survived one of the toughest, scariest, most insane zombie fights I have ever experienced, and charged headfirst into a war zone to save this little trans boy’s life ...

… and I watched as she found the bodies of her dead friends.

The friends who I had killed as Ellie.

The people I felt entirely justified in murdering from Ellie’s perspective.

So when Abby marches out to find Ellie and kill her, I didn’t believe she was wrong. I didn’t want her to succeed, but the game kept making me seek retribution. When the time finally came for these two to have their climactic fight, I literally did not want to throw a punch. I saw the whole situation as really, really sad.

And that is the sign of an amazing piece of writing.

What’s the lesson here? What information can be gleaned for all you young scribes?

You’ve patiently waited for me to get to this, so allow me to share a few things everyone out there should try to inject into their own character’s journeys:

#1) POVs ARE CRITICAL AND NECESSARY, MAKE SURE YOU HAVE ONE.

I cannot tell you the number of spec pilots I read that try to take the ensemble character route right from the get go. They attempt to introduce a dozen characters all at once and give all of them equal time in the early going. They don’t have a viewpoint, and instead take the “God’s Eye View” approach to the situation, seeing everything at the same time.

This simply does not work.

Trying to make your reader care about too many people early on is a sure recipe for disaster. It all but guarantees that you’ll overwhelm them with information, and fail to connect them to anyone in your cast.

You need to pick a viewpoint. Because viewpoint dictates everything.

Lost's pilot came from the viewpoint of Jack. They didn’t attempt to set up everyone all at once. There was time enough for that down the line. As the show went on, each episode started focusing more on different members of the cast. But the episodes had directional clarity.

Game of Thrones starts with the Starks. We see things (the majority of them anyway) from their perspective. And the B plot came from Daenerys’ side. We didn’t cut into Drogo’s perspective, as he rapes Danny in his tent. It was all from her POV, being the one getting raped. It was only later, once things had been established, that the perspective grew to include everyone at once.

And before someone says, “Well, Spike, Love Actually has an ensemble viewpoint, and it’s a classic,” you’d be right … but you’d also be wrong. That movie doesn’t have an “ensemble viewpoint,” it has about ten or so distinct viewpoints. While all those characters weave in and out of each other’s lives, none of them directly oppose each other. You’re getting about ten small stories all told from specific perspectives. The movie still includes POV—just from more than one person.

Give your readers a deliberate way into what is happening in your universe. Don’t just mount us like a camera on the ceiling, watching everything all at once. Be the auteur of your world. Lead us through your story.

#2) HAVING A VIEWPOINT CHARACTER MATTERS, A LOT.

And not just for the reason that you think. The general purpose of a “viewpoint character” is to lead your audience through the early phase of your narrative. Often, this person is oblivious, knows nothing, and needs everything explained to them. By having a lead who knows as much about what is going on as the reader does, exposition stops feeling boring and lame. It feels natural and necessary. Because this character needs it just as the reader does.

If you want a great example of a well-crafted viewpoint character, look at Quinn in Scandal. The first episode starts with this bewildered legal assistant walking into Olivia Pope’s office, not knowing which way is up, and needing everything explained over the course of the first season. This alleviates confusion, and gives the writer a pathway to lead the reader into the story without needing to stop everything and just info-dump. While that is technically what you’re doing, it has a purpose larger than simply speaking to the reader.

Because everyone hates dialogue that repeats things that a character already knows.

The other reason why a viewpoint character is necessary is because, depending on the viewpoint you pick, your entire story could shift. Go back to my example about how there’s easily a game where Abby is the justified hero. Telling a story from a different angle has the potential to completely change everything! Which is why you should …

#3) CONSIDER IF YOUR HERO IS ACTUALLY GOOD, AND IF YOUR VILLAIN IS ACTUALLY BAD.

How does this change when looking at their actions in another way? Is the “bad guy” justified based on his own life experience? And if so, what does that do to your story?

Great examples of this are Ed Harris in The Rock, and Gary Oldman in Air Force One. From the hero’s POV, both of these characters are terrorists who are threatening the safety of the world. But from the villain’s perspective, they are doing what is necessary in order to get justice for their people. They are doing what needs to be done, as they see it.

If you’re a writer, and you can’t craft a story from their perspectives where the movie portrays them as the “good guys,” you aren’t trying hard enough.

Nobody is ever entirely right, and nobody is ever entirely wrong, either. The world doesn’t operate in that way. It’s all a shade of grey. Which leads me to …

#4) MAKE YOUR “GOOD GUYS” DO BAD THINGS.

Ellie does some unquestionably diabolical things on her quest for vengeance. She beats people mercilessly with a lead pipe. She makes deals for information only to shoot them dead once she’s gotten what she wants. She kills a pregnant woman. Does she feel bad for these things? Sometimes. But she still does them.

Pushing your character to the limit of their humanity layers them. It shows that nobody is entirely good. We’re not Steve Rogers who always stands for justice and truth. Real life isn’t quite as pretty as that. Alternatively, also consider …

#5) MAKE YOUR “BAD GUYS” DO GOOD THINGS.

Because this is true to real life too, isn’t it? People aren’t just one note all the time. In reality, hardly anyone is a super evil, mustache-twirling psychopath who goes out of his way to intentionally tie up damsels and leave them on the train tracks.

A common mistake I’ll read in new writers is that their antagonists are annoyingly on-the-nose. They’re rotten down to their core, complete assholes all the time, regardless of the situation. And while I’m sure all of us can name someone who might fit that bill, it’s also a distinct minority of humanity who falls into that category.

Abby did a bad thing when she killed Joel. But she also did a really good thing when she protected Lev (the trans boy) from people who were trying to kill him for just being who he was. Saying that she is inherently bad is impossible, because she is more than the person she was on the night of the murder.

Layering your characters like this allows them to feel complete and real to the audience. They stop being ingredients in the formula of your narrative, and instead come alive and feel authentic and human. Everyone has deep shades to their personality.

But in order to pull this trick off, you need to …

#6) ENSURE THE PEOPLE IN YOUR STORY ALL HAVE DETAILED AND INTRICATE LIVES, ESPECIALLY YOUR VILLAIN.

Everyone is fighting a battle in life that others know nothing about. This applies to your characters as well. Tropey writing will often dictate that the “bad guy” in a story does things because of “that one event from his childhood that changed everything.” But in reality, there are very few moments like this in real life.

Yes, the death of Abby’s father drove her to kill Joel, but her actions that day didn’t make her feel any better. In fact, it’s likely (though never directly stated) that Abby felt … guilty, for what she had done. And that guilt drove her to help two other characters in the game. She went out of her way to aid them because of what she was feeling inside. Her life was more than just one night in a ski lodge with a golf club. And yours should be, too, if you want realistic characters.

There’s actually a word for this revelation … of understanding that each and every person out there has a life that is as deep, intricate, and nuanced as your own. It’s called sonder. It’s a thinking person’s emotion.

Try to make your readers think when they are consuming your stories. About right and wrong. About the true nature of good and evil. About anything you want them to. Just make them think.

I’ve never been a fan of spiders. While I don’t run and hide when I see one, I’ve also never been shy about crushing those little shits whenever they cross my line of vision.

Well, today I found a spider hanging out in my bathroom sink. He was stuck. He couldn’t climb out of the porcelain bowl.

My first reaction was to wad up a ball of toilet paper and smash him to bits. I also could have turned on the faucet and sent the little guy spilling down the drain.

I ended up doing neither.

From my perspective, he was a gross spider I didn’t want in my house. But from his perspective, I was a gigantic monster who he was afraid of. I was the one who might potentially kill him. I was the “bad guy.”

I went into my kitchen, took a glass out of the cabinet, and chased him around my sink for ten minutes trying to push him inside. I finally succeeded.

I walked him out back and dumped him into the grass. He’s probably making a web somewhere, eating a fly right now, as we speak ….

You have Neil Druckmann to thank for that one, Mr. Spider.

Godspeed, and happy writing.

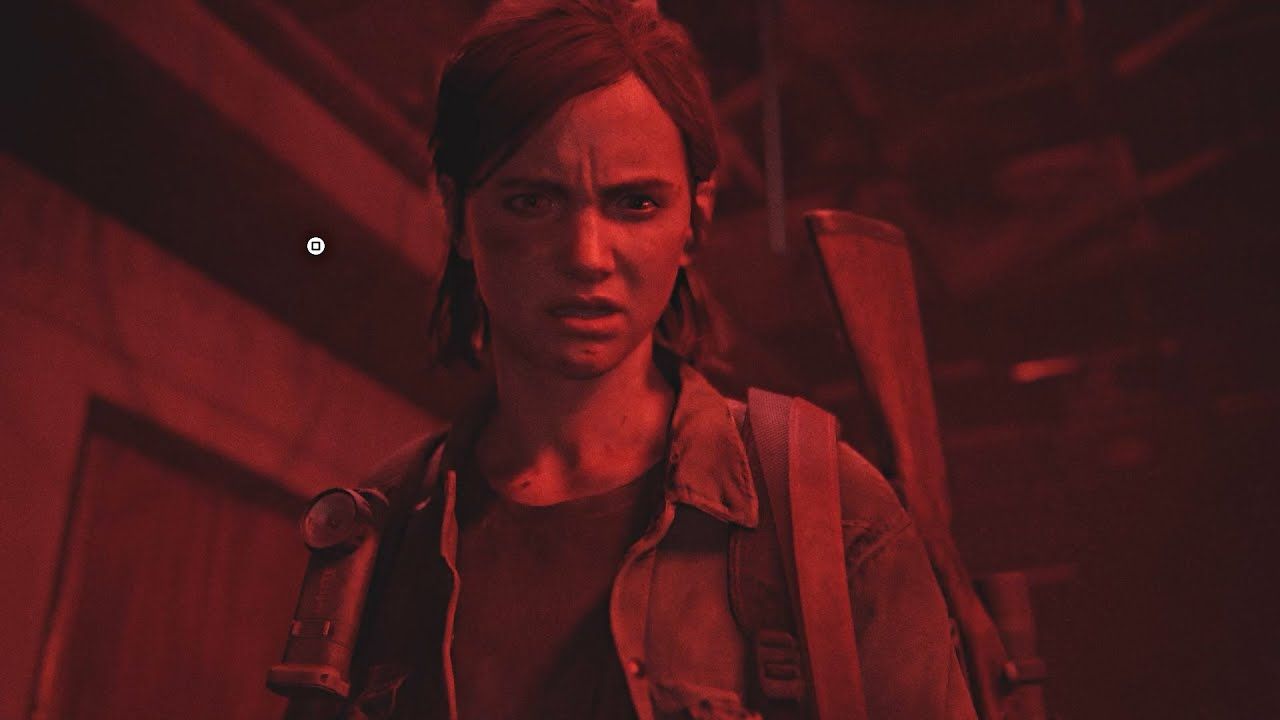

*Feature image from The Last of Us, Part II (Naughty Dog)