The Right to Write

I am currently taking a playwriting workshop with a well-known playwright, Herb Siguenza. There are three other people in the workshop, and it’s been a delight to sit in a room with other writers. But I’m not going to really talk about the workshop per se. I want to write about a topic of conversation that came up.

We were talking about who has the right to write a story.

This may not sound like a thing, but it is, in a few different ways. First, the most obvious: if I am a writer of fiction, am I only allowed to write things that I have directly experienced, from only my own personal viewpoint? Why this becomes a fraught question that people only talk about in hushed, well-insulated rooms is because in recent years, many writers have been erased for daring to write about something that is not in their ‘lane.’

For an example, take the novel American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins, a book about the migrant experience in America. This book came out in 2020, and was an Oprah Winfrey pick. Winfrey tweeted: “From the first sentence, I was IN … Like so many of us, I’ve read newspaper articles and watched television news stories and seen movies about the plight of families looking for a better life, but this story changed the way I see what it means to be a migrant in a whole new way.” So, what’s the problem?

Well, turns out that Jeanine Cummins is white. She has a Puerto Rican grandmother, but the Twitter/X-verse and Goodreads did not see that as enough street cred for her to write an immigrant story. When the book was published, it got high praise from many of the high-level reviewers (NY Times, for example, and Oprah.) Breathless praise for its gut-wrenching portrayal of migrants.

Until … everyone found out who wrote it. Then all the reviewers asked for their reviews to please be taken down, and Oprah backtracked and said we needed a new conversation about immigration. What changed?

The public shaming of the internet.

I’m not advocating for the book either way. I haven’t read it, probably won’t. As a writer, though, I am troubled by this trend of telling people what they can and can’t write.

Many of the books I read as younger person were important and taught me a lot, and they would not have been written if this specific rule applied.

Mark Twain famously wrote about slavery in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which has been banned a gazillion times because it features the ‘n’ word. He portrayed, in phonetic dialogue, the words and experience of Jim, the escaped slave who travels with Huck. (As a side note, I really want to read the new book by Percival Everett called James, a reimagining of the Huck Finn story through the eyes of Jim.)

Now, Twain did live on a plantation owned by his father when he was young. He saw, from outside, the experience of the slaves there. He was very anti-slavery. Today, if he wrote that book, he’d most likely be canceled and called out as a racist or something, but it is one of the most anti-slavery books written, and I believe he wrote it with the express purpose of showing why white slave owners were ridiculous morons.

I’m glad it was written, and I’m glad I read it and taught it in high school.

So, question #1: If you do not come from a specific ethnic, religious, regional, historical community, should you NOT write books about it? What if you interview a lot of people and do a ton of research? Not even then?

My personal experience with this issue happened in 2013, when my novel Out was published. The story takes place in a theocratic dystopia where the Anglicant church has managed to subsume government and entwined it with religious dogma. However, in my book, the heterosexual people were the outcasts. They are called Perpendiculars. Parallels are same-sex couples. And Parallels rule. So, their view is that Perpendiculars are somehow deviant, and need to be fixed and re-integrated into society.

Before this book was even available to read, I got hate mail. One person, who had never read it, said it should be “burned and the earth should be salted so it never rises again.” Wow! Just based on a three-sentence description! People who actually read it understood what I was trying to do. I wanted to show people who, at the time, were arguing for and against gay marriage, what it would feel like to be told the person you love is not someone you can love. I think that idea transcends any identity.

It’s odd to me that no one seems to have an issue with this when it comes to historical fiction. None of us lived through the 1800s, right? But people still write about it. Nobody gets upset, mostly because those people are all dead now. Isn’t it the same issue, though? Contemporary writers didn’t live during the 1800s.

What is different is that, of course, they didn’t. No one expects that. If they are good writers, they do rigorous research and read material written by people who DID live in the 1800s. They steep themselves in the time, the language, the history, the culture. And everyone is fine with that.

The second incidence of this problem is a little bit different, but related. If you have experienced things in your life that involve other people, can you write about those experiences, either as memoir or as fiction?

Current logic would dictate that no, you can’t. You don’t own the stories of all the other people you’ve ever met. But those people are part of your story, so doesn’t that give you the right to write?

I think it does.

I recently had a Hollywood Meeting with a producer about my script for Anna Incognito. There is a key death in the story that is pivotal to the plot, as is Anna’s OCD and trichotillomania. The producer asked me if I had experience with any of those things. I could answer honestly that I had some experience with OCD, but as to the death in the book, no. Not that specific kind of death or that specific incident.

She told me that perhaps I didn’t have the right to write that story. But I did research, I know people who have these afflictions, I know people who have lost loved ones. Grief is grief and illnesses differ, but they also have much in common.

Should I not have written this book or this script?

To this I say: “Fuck off.” I will write what I want to write. If someone doesn’t want to read it, that’s their prerogative, although I’d say everybody should hold their opinions about EVERYTHING unless they have read the book in question.

This disease of everybody having an opinion about everything is threaded through everything in American culture right now, and people are oh-so-willing to cancel other people for any infraction, real or perceived.

It makes me want to write a novel about a one-legged lesbian of indeterminate ethnicity who worships the Flying Spaghetti Monster and lives on the moon.

Maybe I will.

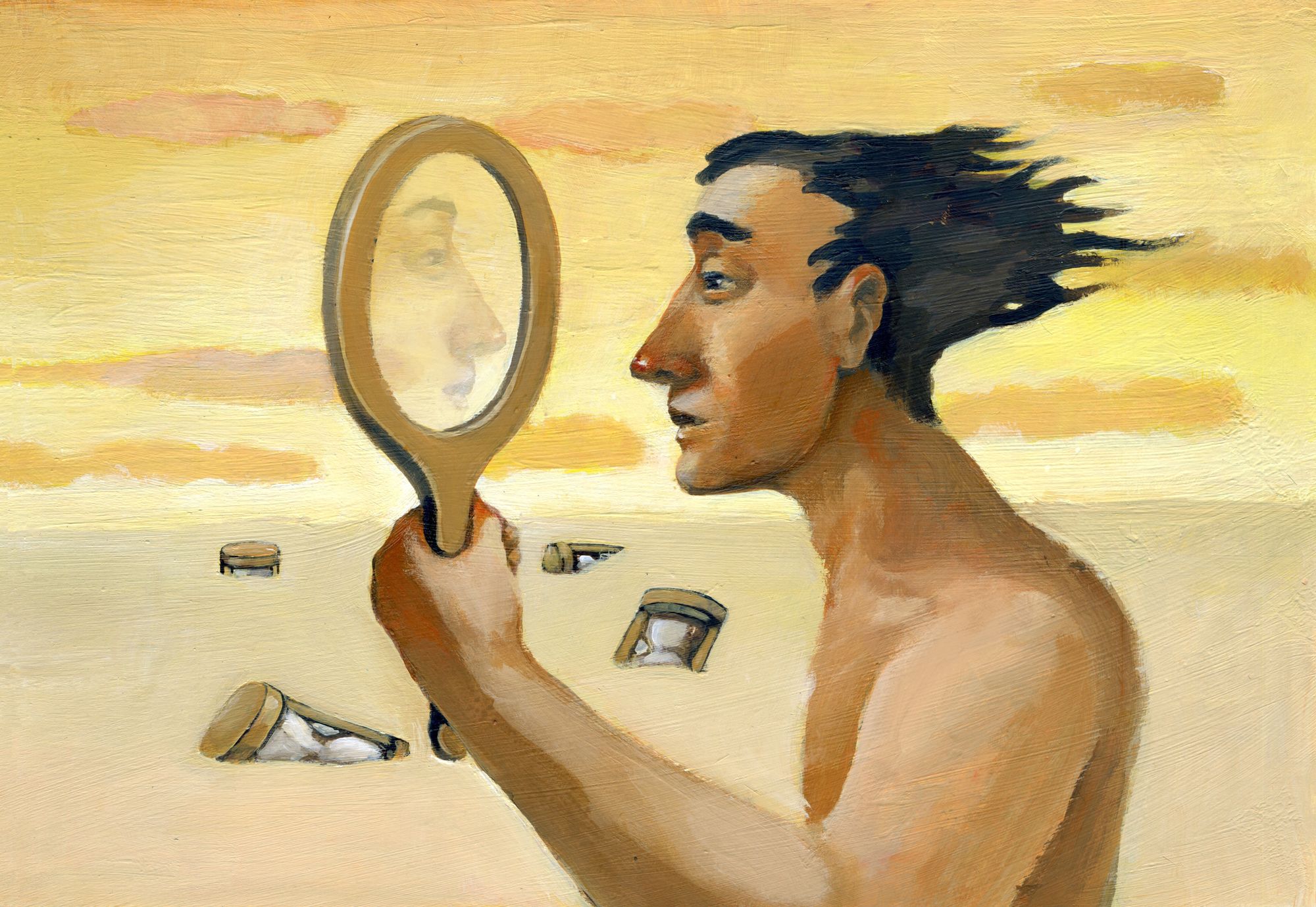

*Feature illustration by nuvolanevicata (Adobe)