Off the Beaten Path: An Interview with Michelle Lerner

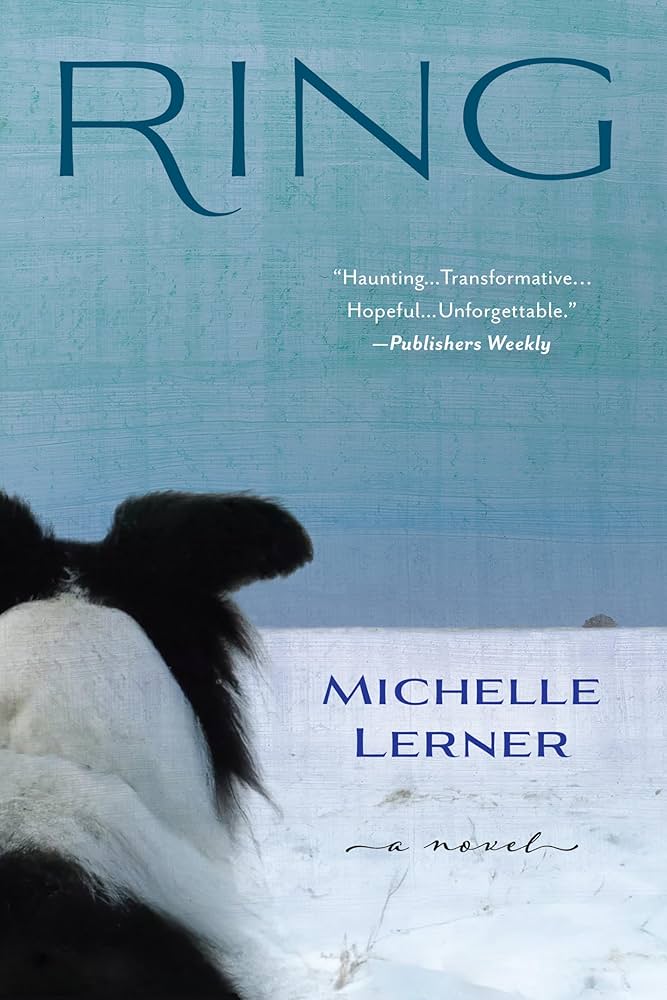

A runner-up in the 2020 Book Pipeline Unpublished competition, Michelle Lerner's debut novel Ring released in 2025. The literary fiction book has received acclaim for its introspective look at grief and the management of tragedy, set against the backdrop of a remote Canadian town.

Ring is, for me, a difficult novel to explain. I almost want to describe it in emotions instead of coherent criticism, because it’s so mesmerizing in its own way, riveting yet with the absence of traditional narrative conflict. A healing guide for the reader themselves. What made you want to write this concept, to tell this story?

My inspiration to write Ring initially stemmed from my experience with complicated grief when I was younger. On and off for a few decades, I thought about writing a story about a person struggling so much with grief that they consider ending their own life, because having that feeling, that impetus, is a common facet of complicated grief.

The vague contours of the story were there years before I became chronically ill: the sanctuary in the snow, the dog unknowingly brought into a life or death situation, and the dilemma that the dog’s presence poses to the main character. The story was about teasing out what moves the needle on a person’s internal barometer regarding their ability to go on after significant loss.

But I did not sit down to actually write the story until I was several years into a chronic illness triggered by a too-long-undiagnosed case of neurological Lyme Disease. At that point, I was experiencing a sense of physical and social isolation due to being sick. I had also discovered, in my attempts to recover from my illness, a range of healing modalities that calm the nervous system and release trauma stored in the body. The relief I felt from these modalities, and from learning to understand the mind-body connection, gave me another entry point to the story. I wrote the book, in some ways, as a healing guide for myself, as well as for the reader.

In terms of the story not having the traditional narrative conflict, I always saw the story's primary conflict as an internal one. And I think that, despite all the external conflicts in our lives, for many of us the biggest struggles are in fact internal, ourselves against ourselves, or ourselves looking for a way to get through the day or month or year. I wanted to write about the struggle to live with something that cannot be resolved. There's a tendency in commercial novels and movies in the U.S. to portray all conflicts as things that can be resolved and all trauma as something that can be fixed. I've noticed that literature and film from other countries is less like that. And a lot of life is not like that. Some things can't be fixed, and we need to go on anyway. That's what I wanted to write about.

You had placed with Ring in our inaugural Book Pipeline Unpublished competition back in 2020. It was for the now-defunct Outsider category. Did the novel start out that way? Something that felt a little off the beaten path of typical literary fiction? How did it help or hurt your goal of publication?

Yes, the novel definitely started off that way, as feeling off the beaten path. I had never written fiction before, other than some short stories in high school. I was a poet—have an MFA in poetry from The New School and have published a lot of poetry since I was young—and I had the desire to write novels but had never taken a fiction class. I had this sense that I didn't know how to do it correctly—how to plot it out, divide it into chapters, develop the right kind of backstory and linearity.

Then one day in 2019, I read an essay by Susan Sontag, from many decades ago, that challenged authors to dispense with some of these conventions. She pointed out that fiction writers were very far behind practitioners of other art forms in terms of jettisoning or transforming the accepted standards of format and structure. That what we think of as a novel is actually just an accident of history, that it's how it happened to develop but we shouldn't feel bound by any of its established rules or standards. I finished reading that essay, opened my computer, and started writing Ring. I wrote it in a very spare way—the first draft, the one I submitted to Pipeline, was even sparer than the published version—and in vignettes instead of chapters and, as you note, without the traditional narrative conflict.

It definitely complicated the book's path to publication. When my agent signed me, she told me I needed to add 20,000 words, more backstory, and a subplot. I was resistant at first, but it ended up making the book better. It still was not commercial enough for the Big 5 publishers, though. I received many complimentary and heartfelt comments from editors, but they all concluded with some version of the book not being commercial enough for their house or imprint. One editor said that they could not publish a novel written in vignettes in lieu of chapters, but encouraged me to find someone who would because they thought it worked.

My agent wanted me to trunk the novel and focus on getting a Big 5 contract for the next book, and then try again with Ring once I was more established. But I was already 50 years old, and that seemed like a long process, and I also had never been set on publishing with a Big 5 press. In fact, I had always had some trepidation about publishing this novel with a large corporation and whether doing so could force me to compromise my vision of the story or any of my ethics. So, instead, I submitted Ring on my own to select small presses. If I'd been wed to publishing with Big 5 or bust, the "off the beaten path" nature of the book likely would have resulted in it not being published.

The answer to this might be obvious, but I’m curious. Why a dog, as this integral figure influencing Lee, the protag?

To some extent, the answer is that it's the way the story came to me.

Years ago, I had an idea for a story that was just an image of someone walking out into the snow, past these pillars, and planning not to return. And then finding a dog. And what do you do when you're on your way to end your life and you find a dog? So the very beginnings of the story in my brain centered around a dog.

But on a more intellectual level, I needed Lee to experience the inherent conflict between wanting to end their own life while also feeling the drive to take care of someone else, and to explore what happens when those two impetuses come face to face. But for this character, it would not have made sense for the "someone else" to be another human. Lee is much too shut down to let another human in, or devote themself to another human at the juncture where the novel starts. So it needed to be an animal, and a dog is really the only species of animal that could possibly make sense in this story and environment.

The setting in the book, Attawapiskat, is an actual town. Why that particular location instead of using a fictitious place? Are the stories mentioned about the locals also rooted in reality?

It depends on what you mean by stories. Everything having to do with the sanctuary, and the character of Ring, is of course made up. I tried to make that clear, or at least disconnect the sanctuary from Attawapiskat, by saying explicitly that the nation had nothing to do with it. And I situated the sanctuary outside the reserve, not inside it. The other stories mentioned, though, the ones the character Matt talks about, are rooted in reality. The Shannen's Dream facility not only exists in real life, but half of my royalties, such as they are, are going to it.

I picked a real place because I was trying to figure out where on the map this story could possibly happen—it needed to be somewhere in northern Canada, with vast space and limited population, and a lot of snow for at least part of the year. A place that an American from the Midwest could actually get to. A place isolated enough for the story to (somewhat) believably happen, but not so isolated that it would seem impossible to reach. Attawapiskat's airport and ice roads made me focus on the land to the west of the reserve, because it met the criteria of being isolated but accessible. I never considered making the setting a fictional place because it would seem like erasure, to me, to pretend that any land in northern Canada is unrelated to Indigenous territory or doesn't have an Indigenous or largely Indigenous nation or town as the nearest community, and it would seem offensive to make up a First Nation. Most if not all land in northern Canada (and in most of the Americas, but very obviously in northern Canada) is the territory or traditional territory of a specific nation, and I didn't want to pretend otherwise.

But, ironically, I was initially afraid to write much about the community, or have a character from the community, because there is, rightfully, a lot of controversy about non-Indigenous authors writing Indigenous characters. The first draft of the book—the draft that placed in the Pipeline contest—mostly mentioned the nation as the place where the airport was, and where the supplies came from. But my agent pointed out that this too was a kind of erasure. That if I was going to situate the story in Attawapiskat's traditional territory, and have it as the only nearby community, I shouldn't exclude it from the narrative and just treat it as a resource, a place to land a plane and get things.

So I did a lot of research, and from the research, I learned not only about some of the things that have happened in Attawapiskat in the last few decades, but also that the ways people in Canadian media write about those things, and about the nation itself, are often problematic. I tried to write about that discrepancy to some extent, the meta-narrative of how this place is written about by outsiders versus insiders (which, I understand, has its own irony given I'm an outsider). I made sure to base the parts of the story that involve Attawapiskat or Matt's character on what residents, rather than outsiders, have written and said, and so I mentioned some things that have actually happened. And I then obtained a few sensitivity reads to try to make sure I did that as well as possible.

Tell us about the process of finding an agent and finally getting picked up by Bancroft. And hey, if you’re comfortable, share some rejections and how they may have changed the course of the book ...

The process of finding an agent started with Pipeline! You and Peter Malone Elliott were the first people to tell me that I should get an agent. It literally hadn't occurred to me before that, because I'd been publishing poetry and poets don't usually get agents. Poetry books, unless written by someone already famous/established, tend to get published through contests and/or by small presses. Once you told me to get an agent and explained that process, I looked up how to do that, and watched a video on YouTube by an agent on how to write a good query letter. I then looked at an online directory of agent manuscript wishlists and picked out a few dozen agents who represent literary fiction and are open to experimental writing, or who mentioned wanting elements that I knew were in my book, like lyrical language or a psychological arc or LGBTQ+ characters.

I expected it to take longer than it did to get an offer. I decided to query one agent every weekday until I either received an offer or hit 100 queries, because an author I admire said she queried more than 100 agents before getting an offer. I think I had sent off about 30 query letters when my agent offered representation. I immediately liked her, and she provided invaluable developmental editing that helped make the novel what it is. But she didn't sell the book because her agency only works with large presses and the editors at the large presses didn't think the book was commercial enough for their houses.

Some of the rejections said the book was too quiet or literary. There wasn't really anything I could, or wanted to, do about that. I think one or two mentioned pacing or that some of the dialogue didn't land, or something like that (it's hard to remember now), and I did some editing between rounds to address technical issues and make it read better. But most of the rejections were about things I didn't want to change, like the structure or feel, and some didn't specify anything in particular other than that they weren't sure how to sell it.

I think every rejection, or almost every rejection, was pretty positive about the story and the writing, and just indicated that the editor didn't think it worked for their house. Mostly because they found it too unusual. The funny thing, though, is that one of the rejections said the book was too close to something already on their list. So it was so unusual that most of the presses couldn't figure out how to sell it, but was too similar to a book another press was already publishing! That really piqued my curiosity—I wanted to know what that book was and read it.

Once my agent gave up on the big presses, I went to small presses on my own, without my agent but with her blessing, because her agency doesn't work with small presses that accept submissions directly from authors. I tried to pick small presses that do the important things that come with Big 5 publishing, like getting reviews, covering expenses, putting out e-books and audiobooks, paying for advertising, doing some marketing, and pitching the story for film. I pretty quickly had interest from two presses and met with the editors. I chose Bancroft because it's been around for 30 years and the publisher does most things that a Big 5 press would do, just on a smaller scale. They even paid an advance, though a relatively small one. Most importantly, I felt comfortable working with the publisher/editor.

When you’re writing fiction in this vein—what I would call “accessible, poetic prose,” though you might say, “well … it’s just my writing”—it can be tricky not to get too verbose, that flowery and melodramatic execution I personally see often in lit fiction. Yet you walk an incredible line throughout. You’re a poet, so this comes as no surprise.

What are some texts, novels or poems or otherwise, you’ve gleaned from? Would you say your background in law helped, in that lawyers are, as I know from secondhand experience, constantly writing?

I do think that in some ways my background in law influenced the writing, but not for the reason you mention. I was always constantly writing, even before entering law. But law school forced me to learn how to write in a very spare and direct way, to be concise. In my first legal internship, I wrote a really long memo for one of the attorneys, and she came to my desk and told me I was writing like an academic rather than a lawyer, that my sentences were too long and had too many clauses, and that I needed to get to the point faster. Learning how to write like that felt pretty painful and constricting to me, and I was glad, when I stopped practicing law, that I didn't have to write briefs or legal letters anymore. But I think that learning to write in that way was valuable because it taught me how to write in a sparer way, and how to discard language that isn't necessary or there for a reason. It definitely taught me not to be flowery or melodramatic—that doesn't go over well in legal writing!

My background in poetry of course also helps with this, and the kind of odd context in which I got my MFA had an impact in this regard. My poetry is generally narrative, but I got my MFA at The New School, which, at least when I went there, was very avant-garde and full of language poets and poets doing other experimental things. I felt like a square peg in a round hole and it was uncomfortable, but it did get me to assess the language I used and to be more aware of every word, every bit of punctuation, and question why I was using it and whether it was needed. It didn't really change the way I wrote so much as hone it. And I think that helped me write Ring the way I did.

But I also should note that I specifically wanted Ring to seem spare because I wanted the way it was written to match what it's about. And I think, at least I hope, that the degree of spareness changes throughout the story as the tenor of the story itself, and Lee's situation, change.

In terms of the texts that I've gleaned from, in some ways that's probably every text I've ever read. But a book that helped me find my voice while writing Ring was the second of the Olive Kitteridge books, Olive Again, a very literary and character-driven consideration of aging and isolation. It's of course quite different than Ring (or, I should say, Ring is quite different than it), but if I had trouble getting into the flow of writing a section of Ring, I'd read a little of that book, and then I'd be able to write better. I think that some of the best written sections of Ring were laid down right after I read a scene or chapter from Olive Again. I also watched the movie The Midnight Sky, at some point while working on the book, and I think the silences and tone of that movie affected the way I wrote as well.

Finally, the way I wrote the character of Lee, and to some extent the book, was also influenced by Tig Notaro's One Mississippi, a semi-autobiographical dramedy series. The series is very serious, but also funny in a dry way, and Tig Notaro's humor, and the way she talks, is very spare and tight, dark and ironic but accessible. One Mississippi influenced not only the character of Lee, but I think also the language I used.

Given the state of formal education, where it feels like emerging authors can learn so much now outside of a traditional university or structured system, what’s your advice to those looking to write in this genre? I know you went to Princeton and Harvard, so perhaps you’re biased … But what do you feel helped improve your writing the most: schooling, experience beyond school, or a mix of everything? And when did you sort of “discover” your voice?

Well, most of the creative writing classes I took were in my MFA program at The New School rather than at Princeton or Harvard, though I took a couple of poetry classes at Princeton as an undergraduate. I definitely think that, in terms of fiction, my writing was improved immensely by formal education. Not necessarily because I took classes on writing fiction—I never did—but because formal education helped me learn how to write prose in general, and because formal education—mostly high school, college, and my MFA program—got me to read a lot of different fiction and poetry and to think about and discuss what the authors were trying to do, and whether they did it well, and how they did it. Writing is improved by reading, and a lot of the reading I did, at least earlier in my life, was through formal education. It introduced me to things I otherwise would not have read, and helped me learn how to analyze the writing.

But that's not the whole story of course. I started writing poetry when I was six years old, though that, too, was in a formal program, a creative writing program during a summer. I then wrote poetry constantly throughout my youth and much of my adulthood. And read poetry on my own. And met and talked to and worked with poets. And all of that helped me improve my writing and find my voice, or voices. So, it's definitely a mix. These days I have the great privilege of knowing and working with other writers, and reading and discussing their manuscripts or published books with them, and I find that invaluable as well, and maybe the best part of being a writer.

In terms of discovering my voice, though, I'm not sure it's a singular thing, a voice. Much of my poetry is, perhaps, in a particular voice, one that I probably discovered at age six and which has grown and developed with me. And that voice probably comes out some in Ring.

But the book I wrote after Ring, currently called A Series of Opinionated Animals, has an extremely different voice. In fact, another writer who just beta read it for me said that she was having a hard time accepting that the same author wrote Ring and that book, because the voice is so very different. She thought it was unusual to be able to change my voice that much. And I guess I would chalk that up to the very different contexts in which I've learned to write, from poetry classes to expository writing in both academic and legal contexts to a place like the MFA program at The New School. I've had to change the way I write, and its sound and effects, so many times because of the contexts in which I was writing, that I think I've developed multiple voices and an ability to move between them.

One thing I think I learned from poetry, and to some extent law school, is to match the writing to the content so that form mirrors function. Who is the character or narrator, what is their mental state, and what is the point of the piece of writing? I try to make the language part of that rather than just the vehicle for describing it.

Fire from the hip, gut reaction: your favorite author of the last 20 years.

Oh no, just one?! There are so many. Since I write fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, can I at least pick one from each genre?

For fiction, I really love Banana Yoshimoto and try to read everything of hers that's translated into English, as soon after it comes out as possible.

For nonfiction, Ta-Nehisi Coates.

And for poetry, Mosab Abu-Toha.

But ... there are at least 20 more writers I'd like to list.