Writer / Director Timothy Scott Bogart: Family Man

Tim Bogart is on a roll. Already finished with principal photography on his next feature, Bogart’s current film, Spinning Gold, drops in theatres on March 31st.

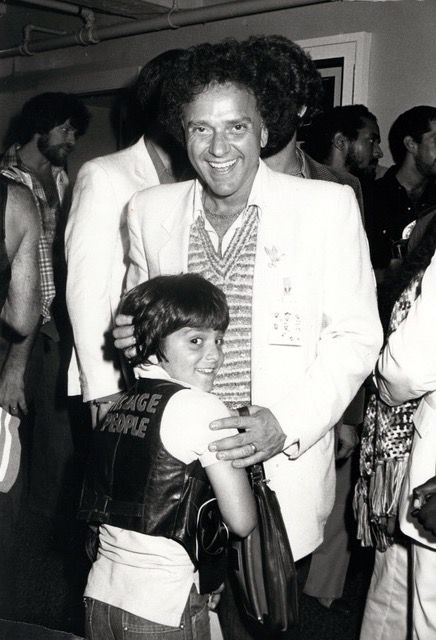

The film documents the incredible life of his father, Neil Bogart, most notably his tumultuous career in the music business and as the founder of Casablanca Records.

A musical powerhouse in the seventies, Casablanca boasted legendary musicians like Parliament-Funkadelic, Donna Summer, Village People, and Kiss. In an industry full of larger-than-life personalities, Neil still managed to stand out.

That Neil’s story serves as Tim’s introduction to a larger stage seems a certain kind of destiny. The influence and inspiration of his father, and the overall theme of family, has been a consistent thread throughout Tim’s work.

I met Tim while we were both film students at New York University. In school, pretty much everyone imagines their future selves as wildly successful filmmakers. But even among all those aspiring auteurs, Tim stood out as something special.

A unique force of nature and restless to go at his own pace, Tim successfully talked his way into sophomore production classes during his freshman year. He was clearly going to do things his own way.

Following school, Tim’s professional career has been anything but typical (if a typical Hollywood career even exists). And while perhaps not having as chaotic an industry experience as his father, Tim has weathered his own rollercoaster of hits and misses.

After starting out as a development executive at a production company, Tim went on to form his own. At Wolfcrest Entertainment, he was free to try new ways to create, pitch, and distribute stories, not held back by how others had done it in the past.

Producing pilot presentations, new media, and some of the very first commercials for Skechers footwear, the Wolfcrest chapter culminated in a live action Jungle Book series for the Fox Kids Network.

Clearly setting the stage for his own future biopic, Tim brought an actual black bear to the pitch meeting as a nearly seven-foot-tall proof of concept. Needless to say, "Mowgli: The New Adventures of the Jungle Book" was greenlit, and reruns still air around the world today.

The turn of the century saw Tim as a screenwriter and producer for hire, as well as a creator of the pilots, “Extreme Team” for ABC and “Conspiracy” for Lifetime. Somewhere in between, he found time for his feature debut as writer and director of the indie, Touched, starring Jenna Elfman.

Despite working as a “solo act” during this period, the continuity of family persisted. Whether it was literal blood relatives, or the extended family of trusted friends and collaborators, many of the same names would crop up in the credits of his projects again and again.

In 2011, Tim embraced his entrepreneurial spirit once more with the launch of Boardwalk Entertainment Group, the name an homage to his father’s Casablanca follow-up, Boardwalk Records. The family connection was more profound than ever as the partnership included his brother, songwriter, Evan Kidd Bogart.

Productions included music reality competitions, “Majors & Minors,” and “Platinum Hit,” as well as the long-running TLC series, “OutDaughtered,” Executive Produced by his other brother, Brad Bogart.

Now, with the imminent release of Spinning Gold, Tim embarks on a whole new chapter of his career. Despite shifting iterations, delays, and false starts, all the struggles to get this production to the finish line are in the rearview mirror.

I managed to get Tim to sit still just long enough to answer a few questions ...

James Hereth: At more than twenty years in the making, Spinning Gold definitely qualifies as a passion project. How did the shooting script compare to your original conception of how Neil Bogart’s story should be told? Did the practicalities of budget or music rights influence what parts of the story were included and what parts were left out?

Timothy Bogart: It's interesting, I probably thought about how to write the script for the better part of ten years before having the clarity to finally write "Fade In." How do you tell the story of a life? What part do you focus on? What part matters? Where to begin? Or more challenging, where do you end? Aside from chronicling the events of a life—what’s the purpose of doing it at all? Is there a theme that rises above it all? How do you honor a life so important to you—while making something others can be entertained by?

In truth, the main struggle from the earliest days was how to find a structure that mattered at all. The secret way in, ironically, was evident in the way I avoided actually writing it. Instead of taking someone through a linear, beat-by-beat outline of what I thought the film could be—every time anyone asked me about it—instead, I chose to cheat in order to get their interest immediately by simply saying, “Let me just tell you his greatest hits.”

I don’t know why it took so long for me to understand what I had already been developing. I always knew that I wanted the film to be both a confession and a final argument. A person at the end of their life struggling to justify the sum of their life. And if that’s what they were really doing—then, they, too—would choose to focus on their “greatest hits.” The moments that transcended the life, itself.

I was actually in a meeting one day at Endeavor with a table of about ten agents. I hadn’t written a single page. But I sat before them and just rattled off story after story—the greatest hits of his life. And seeing them all rapt in attention, it was that day I realized I actually had already been playing with the structure all along. Neil would be pitching us his greatest hits as a way to try to justify his life—and through that, we would come to either judge, or embrace him. Support, or condemn him.

And since it was his final confession, he would become the ultimate unreliable narrator, showing us only what he wanted us to judge. For better or worse. And once I finally embraced that, the first draft—while nearly 200 pages—wasn’t really all that far off from the final shooting script—it was just longer!

As for the music, I just wrote the scenes I felt moved the story—and included the songs, that I felt drove that narrative. While the music rights were challenging, I started early enough in the process to know that I could ultimately use what I needed to.

Hereth: A true-life story can be a very tricky balance of fact and dramatic license. Did you have any self-imposed “rules” for what you would or wouldn’t change?

Bogart: The challenge here was that it wasn’t just a true-life story, but a true-life music story—and history is clearly marked and delineated by release dates. A song on an album happened at the time that album actually was released—and using so much music in the piece created an incontrovertible timeline that I had to adhere to.

That said, from the very beginning, I knew I was not interested in simply recreating the masters that we all know and love and have been listening to for decades. Who could possibly compete with Gladys Knight’s actual master of “Midnight Train?” Or Bill Withers’ “Lean On Me”? These are some of the most cherished music masters ever pressed in vinyl.

But that was never what interested me. I never thought it would be that interesting to try to recreate what we already knew—I wanted to dive into what we didn’t know. I wanted to explore the origin tales. I wanted to know what it was like the first time Gladys ever sang “Midnight Train”—the first time Bill Withers ever thought of “Lean On Me.” I wanted to dive into the first drafts of music.

That’s where I thought there was new terrain to explore.

We all know “Beth” became a massive transformational hit for Kiss, but few know how close that song never came to actually being. We all know “Love To Love Ya Baby” helped launch an entire genre of music and a cultural release—but few realize it was initially released and was a flop. Those are the details I found interesting. And once I made that decision, it provided a critical path to being able to open up that timeline to see how all these different artists’ paths were evolving along with my father’s.

That said, the self-imposed rule was to stay true to what ultimately happened and, most importantly, to the essence of what happened. While so many of the stories seem too good, or too crazy to be true—every story we explore in the film actually happened. Were there a few instances where I needed to tighten the timeline? Yes. A few places where I combined scenes to make the structure work? Of course. But the underlying stories of each one of those stories—those are all true and fidelity to that, ultimately, was the compass that steered me.

Hereth: How much rewriting did you face during production? Did weather, or scheduling, or a worldwide pandemic force you to make revisions on the fly?

Bogart: Well, this film, perhaps more than most, had a dramatic journey from beginning to end. We started shooting before the pandemic, and then were shut down for one year and eleven months before we risked shooting the rest of the film with no Covid insurance. We even moved the production from Canada to the U.S. since we had no way of knowing if a new Covid variant would shut down the borders and collapse the production again. We actually packed and stored the sets and wardrobe and props and trucked them all to New Jersey where we finished the film.

The whole struggle to complete the second half of the film became a remarkable meta-parallel to the struggle my father faced with keeping Casablanca alive. In spite of all the obstacles against him, my father refused to ever give up on the belief he had of what he knew he could do if he could just survive long enough to do it. In the end, and I believe Jeremy Jordan, who plays my dad, has echoed in a couple discussions along the way—the film became as much about our own struggle to keep it alive as my father’s to keep Casablanca from collapse.

And there’s no question that struggle informed constant rewrites to the very end. I’ve always been the kind of writer who can effortlessly toss aside years of my own work in the light of the reality that it’s just not landing. And so, that for sure, was the case here. I knew the challenges we were facing making the film and felt those parallels needed to be felt in the film.

Hereth: Years ago, you wrote and directed your first feature, Touched. How have you grown as a writer and director since then?

Bogart: I think in both regards, I have become ever more grateful for the opportunity to do it all. I remember with Touched, which I adapted from a play I had written, it came after years and years of near-misses where other films I had been working to put together just didn’t get to the starting line. In that case, I had just seen two other films of mine over the prior two years get right up to the start of prep and for various reasons, didn’t come together.

And with Touched, I had put together $3.3M to finance the film—with $3M from a foreign sales company and $300K in equity. And two weeks before production started, that $3M from foreign fell out! Indie financing is not for the weak at heart. It’s brutal.

And there I was, seeing another film slipping thru my grasp—and I knew my leading actress, Jenna Elfman, had a very small window because she was starting another series. So, I called up my line producer and told him don’t ever tell anyone that we lost the $3M—we’re gonna make the whole thing for $300K! And cutting it down to 13 days, if I recall—we just refused to give up.

I actually don’t think I’ve ever told that story before! But even with an opening night slot at the Boston Film Festival—it was a tiny film that became a TV movie—and I found myself back to square one trying to get a grown-up film made!

As a writer, there’s no question every project, every draft, made me more capable. As a producer, I ended up working with so many first-time directors and was always able to help steer their course in the way I wished someone had been able to steer mine.

So, in the end, when finally able to direct Spinning Gold—I just felt grateful. With the gift of another chance to see what I had in me. And then to have to shut down during Covid! The cliché is what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. In this case, I even had a deadly serious health crisis during Covid that really did almost kill me!

Finally, back on the set in New Jersey to finish the film—I felt I had enough war wounds and mileage—and tremendous appreciation for the extraordinary gift I was given to do this thing that I love—that I have to believe there was a maturity and grounding to my reality that informed the work.

Maybe this is just justification! But I don’t believe it would be the same film without the struggle.

Hereth: You have personal relationships with many of the people portrayed in Spinning Gold, obviously including members of your immediate family. Did you feel a responsibility for protecting them or portraying them in a positive light?

Bogart: No. I really didn’t. And that may seem strange as it literally includes my dad, my mom, my step-mom, my aunts and uncles—and then the music artists, like Gene Simmons and Donna Summer, who all were just as close as family! But no, I knew from the start that trying to have some form of understanding with them about how I would portray them or the events would create an impossible conflict.

I also always knew that as the son, I’d be judged for glossing over what was clearly a time of sex, drugs and rock n’ roll—but the truth is, I was searching for characters that were real and complex and that meant they had flaws like the rest of us. In fact, I absolutely believe that without my father’s flaws, there could never have been the success. If he wasn’t an addict and a gambler, there could never have been the triumphs. But even more than that—he was in love with two women at once—and yes, I could have played that down, but I found that fascinating and something that was real and messy and complicated and worth exploring.

I’ll tell you what I did do, though—I interviewed anyone who would sit with me over the years, and I asked what part of their life story they felt hadn’t been told. And this extends to Kiss and Donna and Parliament and the Village People—and yes, my family. And I told each of them—I was still going to tell the parts I felt were most interesting—but there’s no question, in most instances, the stories they felt had not been told fully, or properly, happened to be the most fascinating ones!

Hereth: Let’s talk about your process as a screenwriter. Do you write a script differently when it’s something you’re doing for another director, as opposed to a script you plan to direct yourself?

Bogart: I really don’t know how to separate the vision between writer and director. If I had to analyze it, I think as a writer, I am always writing for me as director—whether there’s even a thought or not that I might ever direct it. I’ve always felt that writing was a path, but directing was the actual thing.

I think that became most clear for me early on when I was directing challenging, lower-budget television. I would agonize over the script—struggle with the producers and network—then get on the set to direct what I had written, and suddenly, with my words in real people’s mouths, and trying to block in real environments, as a director, I would humorously condemn the writer-me for boxing in the director-me. And I had to be ruthless in my ability to discard what was precious to me as a writer to fulfill the need of the piece once it actually began to take on a life of its own beyond the page.

And that has always stayed with me. I write what I want to see—which inevitably brings the director’s voice into the equation. And the writer serves that voice. At least for me.

Hereth: A lot of creators struggle to find time to work on their projects. As someone who wears many metaphorical hats—producer, director, executive, dealmaker, etc.—how do you find time to write? Is there a specific slot carved out in your schedule, or do you just fire up Final Draft when you see an opening?

Bogart: Writing is a job for me. And that demands a rigid and consistent work schedule. And that means whether it’s actually a real job, meaning getting paid or not. It’s a muscle—and I know this is also a cliché—but I absolutely believe when you don’t write consistently, that muscle atrophies. I also believe, at least for me, writing requires me to be in a different head space than anything else I do. I can’t write and also take a production call. I can’t write and take a break to go to the grocery story. When I write, that’s all I can do.

And for me, and this goes back decades, I can only write in the morning, and usually, really, really early in the morning—before the rest of the world awakes. Generally, I will wake at 5 a.m., roll out of bed—still groggy in a semi-dream space—grab that cup of coffee and write for 4-5 hours before the world rushes in. Once the calls and emails start, I’m out and just can’t find the rhythm and space again until the next day. And when I’m really in a writing period—that means seven days a week—even a day off fractures the momentum and weakens the muscle.

Now, as a working writer for others, there’s not as much luxury and sometimes, yes, I need to fire up Final Draft and just burn through some shitty pages mid-day just to get some more in the file—but it’s never my strongest work.

Hereth: Your credits include projects in all sorts of different formats and genres, from features to series to reality shows. Do you have a favorite arena to work in? A favorite genre?

Bogart: Maybe I get this from my father, but I’ve always had an entrepreneurial spirit and therefore, can get intrigued by perhaps too many things. A reality series? I don’t watch them. But trying to crack one? Yeah, that gets me. TV versus Film? The dividing line is so thin these days I don’t know that the distinction really matters that much anymore—the work is the work.

As for genres, I have an enormous appetite across almost all genres—it’s more the underlying theme for me. Which can be resident in a sci-fi piece just as much as in a romantic comedy. So, no, I don’t feel I have a favorite arena or genre—it’s more about whether I can sink my teeth into something that I feel I want to explore about people being people. Humanity—and inhumanity—I think that’s what interests me. Why do we all do the things we do?

Hereth: What films or screenwriters have influenced your writing? Are there any television or streaming series that have made an impact on you as well?

Bogart: As far as writers—this may also be a cliché—but Cameron Crowe and Aaron Sorkin are pure masters to me. They take subjects others may not see the value of the journey in, and infuse such humanity in it. And, they each have a poetry of their own language that becomes music all its own.

I have probably watched the entire series of “West Wing” fifteen times. No joke. And every other Sorkin piece he’s ever done. And Cameron Crowe? There’s just no one who gets under the skin of who people not just are, but who they aspire to be—as those two guys. I can watch anything of theirs at any time. The downside is, when I do, I know I can never attain that level of poetry. But they do inspire me to work harder! Even something like “Newsroom,” which has much more blowback from some, I find extraordinary. Even Crowe’s “Roadies”—which few people cared about—I found moments of pure revelation. Michael Clayton was always a piece I found just extraordinary. Again, a writer at the top of his game—in that case, taking on the director chair.

There’s a lot of great television today—“Marvelous Mrs. Maisel,” “Succession,” “Ted Lasso” and this year’s “Shrinking”—again, I think the common theme in them all is how human beings play out being human in their messiest forms. That’s what intrigues and inspires me.

Hereth: Your new venture, Hero Entertainment Partners, is very much continuing the Spinning Gold template of music-driven projects. Do you think growing up in a musical family has been imprinted into your DNA? Do you see yourself ever writing music itself in addition to music-centric stories?

Bogart: There’s no question my musical lineage plays a part. I just see the world through music. Even back at NYU Film School when I was just figuring out who the hell I was at 17, I would put on my Walkman and walk thru the streets and parks and subway and see the world through the music I would listen to. I can’t, nor do I want to, separate how music informs what we feel—and so those pieces draw me to them. They just do. Even in the most dramatic kind of piece—I can’t help but think of the sonic signature.

In a film we’re producing at Hero, with Jim Sheridan directing—while it’s about Jim’s own life story growing up in 1960’s-1970’s Ireland—we’re working with Bono and The Edge on both original songs and score that they’re writing that is helping to form the spine of the piece. Certainly, with my latest film I just wrapped in Italy, Verona, it’s a full-blown musical! And with the MTV story on the way, as well—it’s just who I am. But, writing music? I leave that to those who can do it!

Hereth: Speaking of music, back in the day, I recall you playing soundtracks as you wrote that spoke to the stories you were creating. Is that something you still do? What other tips or advice for aspiring screenwriters can you share?

Bogart: Hah! You know, I have no idea what made me start to do that, but yes, that is still an absolute requirement for me. It’s Pavlovian. Trying to sit down to write each day is the most abnormal thing someone can do. Suddenly saying, OK, I’m gonna stop worrying about my rent, or my car repairs, or my family or whatever—and I’m going to just create now?

I mean, how does that work? You have to trick yourself a little, at least I do. And music does that for me.

Whenever I start a draft, I identify a score that feels evocative to me—something that feels right. And once I start associating that score with that draft—when I start my sessions each morning—and I turn on that score, that Pavlovian trigger takes over and it transports me back to where I need to be for that space. Music just works on the brain that way—instantly making you feel something with just a couple notes.

So, yeah, I’ll listen to that same score, over and over and over again for the entire draft—and then, sometimes, when I move to a new draft—I change the score! Which makes me have to look at the material through a new lens with a new heartbeat and a new rhythm. I find it incredibly helpful.

The other thing I do, which I highly recommend—even though it may add time to the session—is I always start my day on page 1! Even if I’m working on the third act. I find it so much more informative to start each day at the beginning and ramp up to the actual new work. But, along the way, I can’t help myself from revising those earlier pages. The funny result is a first half of a script that’s been revised a million times more than the 2nd half! But the first halfs, I think, are usually far more important to crack.

In the end, the only two pieces of advice that really matter, I think—are the two most often told—if you want to be a writer, you just have to write! All the time. Paid, not paid, short form, long form—it’s a profession that requires nothing more than a piece of paper and a pencil, so there’s no obstacle but ourselves. And, even more important? You have to keep rewriting! Over and over and over again. It never ends until you can buy it on Apple TV! Well, and even then …

As Spinning Gold hits theaters, Tim will have only recently returned from Italy filming his follow up, Verona, a musical take on the real-life story that inspired Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

Having observed Tim, both up close and from a distance, I can say that he’s found his way to this point by believing in himself, working hard, and pushing through setbacks to set the stage for the next success.

And as he heads in that direction, Tim’s ever-present family connections are stronger than ever, as his daughter, Quinn, has already begun working by his side as a 2nd Unit Director.

An ongoing creative legacy that’s as good as gold.

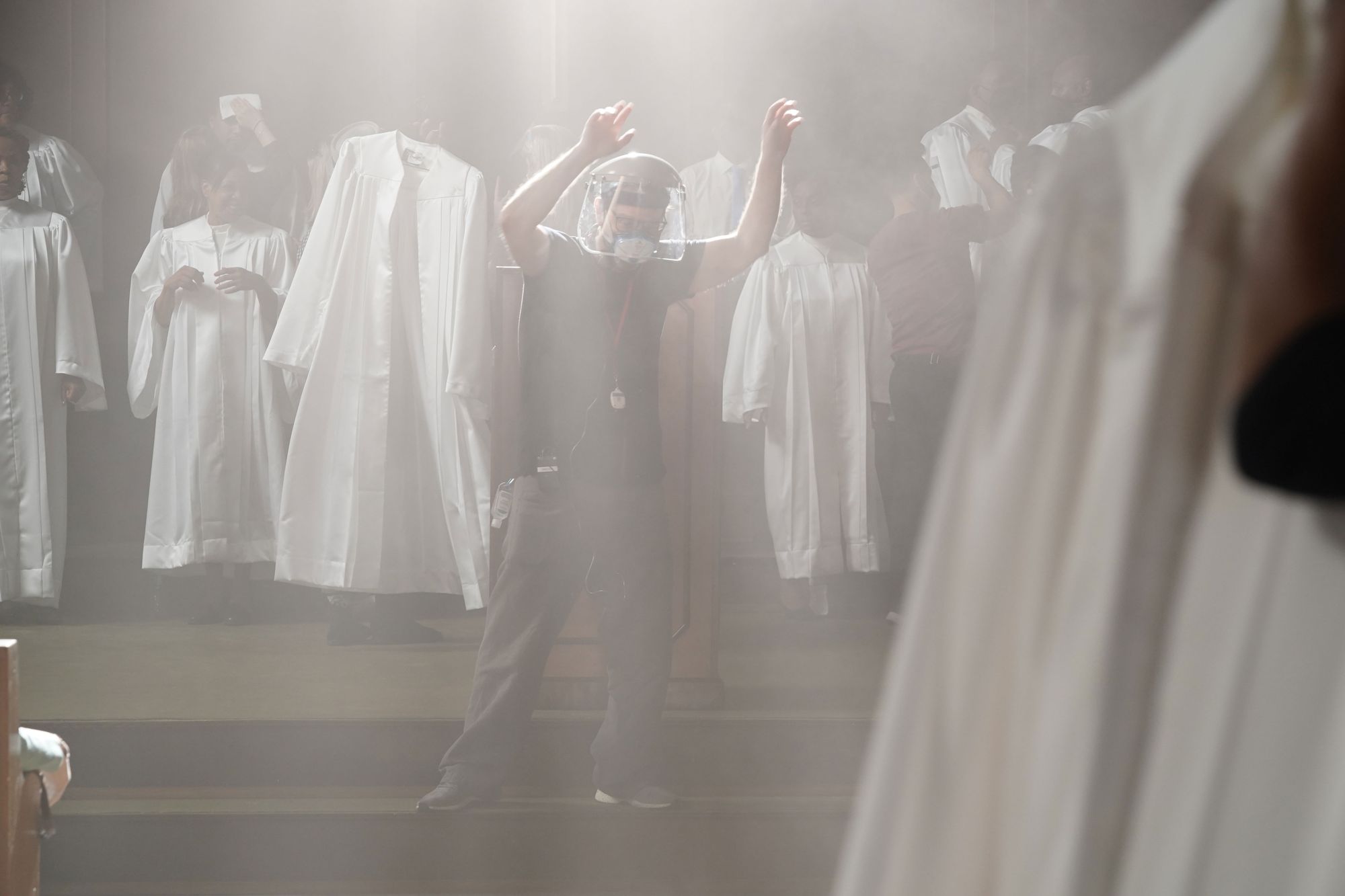

*Feature photo Timothy Bogart, Spinning Gold